The Balakan-Lagodekhi frontier between Azerbaijan and Georgia is our current location. Having passed through passport checks in Azerbaijan, we commence trundling our suitcases upwards along paths and ramps to exit one Caucasian country and enter another. The final flag in Azerbaijan billows farewell, while a smaller Georgian flag, along with that of the EU (notwithstanding that Georgia’s application for membership is effectively at a standstill at time of writing) waves us welcome, along with the new female guide for the next few days.

Kakheti

We are in Kakheti, Georgia’s easternmost region, famous for its wine. Wine making in Georgia has been added to UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage and, right now, it is grape harvest season. Oh good. After exchanging leftover Azerbaijani manat to Georgian lari at a handy currency exchange place we make for our first stop in Georgia: somewhere in the countryside for lunch with the locals. A long table is laid under a canopy, from which dangle bunches of grapes. And adorning the table is a decanter of the local fire water and carafes of red and amber wines. Amber wine, we are informed, is made of the same grapes as used for white wine, but instead of removing the skins after crushing, like conventional white wine making, the skins are left in the liquid for sometimes several months. The colour turns to amber. Not sampled this before. Always willing to try something new. Far too much of this outstanding Georgian wine is imbibed, along with local bread and meats and soups and salads and grapes and fire water. Phew.

As we leave our lunch stop, in convivial mood I have to say, we pass trucks and tractors lining the road, loaded with grapes bound for wineries. We also are bound for a winery. Seems fitting after all that lunch and alcohol to visit a winery immediately afterwards. Well planned!

Khareba Winery

The road onwards follows the Alazani river. Not much water in it. Anyway, we soon enter the environs of the Khareba Winery and are welcomed by our hosts into its cellars. The Soviets were the ones who built tunnels penetrating deep into the hillside specifically to store wine, we are told. This done in order to keep said wine at a constant temperature ‒ between 12 and 14 degrees C. A young man in suit and tie treats us to a little talk about how wine used to be made here. Deemed necessary as a prelude to the tasting. Thence to long polished tempting tables upon which are long neat rows of sparkling wine glasses. The young man swirls the wine in glasses before serving in succession two dry whites: Tsitka from the Khareba winery and Tsolikouri from Monastery Qvevri, and a dry red: Mukuzani from the Khareba winery. With bits of bread and local, rather unappetising white cheese. Spittoons provided but I don’t observe anyone making use of them. All rather jolly. Not at all surprising.

Stagger into the coach for the onward journey. The coach is not as spacious as the Azerbaijani one. Seats are closer together. Moreover, the Georgian roads are noticeably potholed. Georgia does not have the benefit of petrodollars from oil reserves in the Caspian Sea, as does its neighbour, Azerbaijan.

Aside from being the earliest producer of wines, our Georgian guide tells us, with the longest unbroken tradition of winemaking anywhere, Georgia is also the largest producer of hazelnuts in the world. Oh OK. Will file that bit of useful knowledge away somewhere.

Gremi Monastery

Our final stop for the day is the Gremi Monastery or Church of the Archangels Gabriel and Michael. It is a splendid sight from the road. Perched atop a steepish hill with steepish steps leading to it and a gurgling stream flowing to one side. Picturesque with the surrounding trees wearing their autumn colours.

Ascend the steps and pass through the gate in the old stone and brick built castle wall, which surrounds the complex. The town of Gremi was once the capital of the Kakheti Kingdom, we are told. The citadel, once a thriving centre on the old silk road, was destroyed by the Persians under Shah Abbas I in the sixteenth century, and the church complex, built by King Levan in 1565, is all that has survived. Next to the church, also built of brick, is a three storey tower, the top of which has a belfry and lower floor of which has a museum and gift shop.

Georgia was one of the first countries in the world to adopt Christianity, incidentally, in 337 AD. Georgian Orthodox. And its flag portrays five red crosses, the large one, the cross of St George, representing Christ, the other four representing the Four Evangelists. Adopted in 2004 – the flag I mean. In the church there is a service going on with incense much in evidence. A priest behind the iconostasis is chanting and a lady this side of the iconostasis is singing responses. Sublime. Three part polyphony is the tradition in Georgian chant, but I only make out two voices. Anyway, a little peeved, the lady appears, at the tourists taking photographs of the interior of the church with its faded frescos during the service. Not too respectful, I feel. Amongst the frescos is one of King Levan holding the church. His tomb is also within.

Would like to linger longer but the group is mustered and I have to leave, with that fleeting bit of spirituality in my ears, and a stunning view over the Alazani valley from the doorway.

From here we head to Telavi, the administrative centre of Kakheti, for the night. Another dinner included. Putting on the pounds.

Telavi

Although now located in the attractive medieval town of Telavi, which sports several interesting monuments amongst its ancient splendours, and an equestrian statue right in front of the hotel, for some reason, best known to the tour operator, we are bussed to an agricultural market. There to peruse pumpkins, large healthy looking tomatoes, live fish and cheeses, and a speciality of the region called churchkhela, which we tried at lunch yesterday, like a lump of tasteless gelatin, moulded into sausage shapes, (actually supposed to be candle shapes made of walnuts and grape juice) and a pig’s head. We footle around for thirty minutes or so. All very colourful and cold up here with the snow atop the mountains close by.

Qvevri

The premises of the Master of Qvevri (wine vessels) making is the next destination. It is all about wine here in the Kakheti region. The coach ventures down an unmade narrowish, muddyish, potholed road with peach trees, which the bus scrapes upon passing.

Awaiting us at the gate of his qvevri making establishment is the Master. We are welcomed within, and wander past large earthenware qvevri, lying decoratively about his garden, towards a stone building where he demonstrates his art. He begins to form the vessel from soft clay (he now has to purchase the clay, while once it was free, the guide tells us), and shapes the bottom of it. Each layer has to be dried for a couple of days so that it is hard enough to place the next layer on top of that one, and so on until the vessel goes inwards at the neck and makes a nice egg shape.

The finished ones we see are about six feet tall. Qvevri making began, according to archaeological evidence, in about 6000 BC in eastern Georgia, where remains of some have been found. The tradition has been passed down the generations and has made it onto UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage List. The guide informs us that it can take eight weeks to make one of these vessels, the largest of which can store 3,500 litres of wine.

We are shown the tools of the trade, such as stirring tools and a grape press, and long implements with cherry bark on the end with which to clean the insides. Said cherry bark apparently contains a natural cleaning product. Once full, the qvevri are buried in the ground with their rims just above the surface and sealed. There to ferment and mature. This is the traditional way of wine making, not the same as we saw in the Khareba wine cellars yesterday. We are told that it is not possible to control the temperature quite so well as within the tunnels.

Having viewed the accoutrements of the qvevri master’s trade, now is the perfect time, mid-morning, for the wine tasting. Served with dried apricots and walnuts and some of that same tasteless cheese as at Khareba, first up is amber wine – Kisi – followed by red wine from the Saperavi grape. Excellent, although coffee might have been more sensible at this time of day. In the tasting room are some qvevri buried underground.

Wander back to the bus through the Master’s garden, also adorned with an old ‘Moskvich’ Lada, and a little fountain and pheasants in a coop. Thence, we follow the road parallel to the snowy Caucasus range. Parked alongside the road and/or driving ahead of us are trucks and trailers piled up with grapes. And myriad signposts pointing to wine routes and wineries, and vineyards with their vines in neat rows sloping downwards.

Tsinandali Estate

Next stop is the Tsinandali Estate, which at one time belonged to a 19th century nobleman, poet, polyglot and Lieutenant General in the Imperial Russian Army, Alexander Chavchavadze. He it was who introduced European wine making techniques, as well as piano music and billiards, to Georgia. He planted his gardens with plants and trees from all over the world. Very pleasant they are to stroll around too. A large stone head lies under old trees in the grounds, presumably that of Alexander himself. And a large pond with fish and water lilies lies in front of the house.

The Soviets appropriated all such properties and handed them over to families to live in, for the sake of equality, we are told. The house is now a museum, full of old prints, porcelain, pianos and antique furniture.

Thence to lunch. The abundance of food and alcohol on this trip so far in Georgia has been astounding. Another charming venue in a large room with a long wooden table all laid out expensively for us. Aubergine salad, tomato and cucumber salad, spinach and cheese pastry things, pork chunks and chips; chicken in a spicy tomato sauce. Wine.

Sparkling water is on offer. Loath as I am to pass up on a glass of the divine Georgian nectar, I opt for water. Scarcely recovered from yesterday’s over-indulgence, let alone this morning’s. The balcony of the restaurant oversees acres of vines stretching as far as the distant trees and mountains.

Sighnaghi

We follow a rusty coloured tractor for a mile or three after lunch. Stashed with grapes. The coach driver eventually accomplishes his mission to overtake it as we drive to Sighnaghi, the ‘City of Love’. Glad to have claimed the front seat today. Meandering south-eastwards on a winding potholed road. Hairpin bends. Queasy making. The bends are so tight that the driver misses one of them, continues up a side road, reverses into a parking lot, and comes back again in order to proceed.

By the time we arrive in the City of Love, we only have about 30 minutes to enjoy the place. Time just to wander up the cobbled road and see the 18th century defensive walls of the castle, built by King Erekle II, and St George’s church in the distance, with the background of the Alazani valley and the snow skimmed Caucasus. Spectacular views and all that, but a significant detour as we now head west towards the capital.

Tbilisi

It is a two hour drive to Tbilisi from here with a stop for washrooms. Sun low down in the west. Horrendous traffic in these eastern approaches to the city. Hotel is some distance from the old centre, we soon find out. It is nearly 8 p.m. The occupants of the coach are becoming grumpy. Have to seek out a late supper in the slightly seedy surrounds.

The next day, our guide is hoarse, not from declaiming too much but as a result of a noxious cold. She has taken the somewhat belated decision that another guide would best serve us. But he won’t be along until later. OK. Head back into the breakfast room.

Bussed, without guide, to the National Museum of Georgia. Much sombre stuff within, especially the bits about the Soviet occupation and the atrocities carried out here in 1921. But also some fascinating info about the ancient kingdom of Colchis ‒ part of West Georgia on the Black Sea coast ‒ and the Jason and the Golden fleece myth. The myth stems from the fact that local villagers would use sheepskins to collect deposits of gold from the mountain streams. Hence golden fleece, sought, in ancient Greek mythology, by Jason and the Argonauts on the good ship Argo. Gold miners today use the same method to capture flakes of gold from the streams apparently. Coins on display too. Large numismatic depository here, according to the info given. Coins were minted in various places in Georgia, and the earliest were found in Colchis dating from the 6th century BC. Elsewhere in the museum is an array of stuffed birds and mammals, along with skulls of early hominids, the earliest in Europe. Eclectic mix.

It is midday before the new guide meets us outside the museum. Lanky chap with rangy beard and dark glasses. Wearing jeans and carrying a backpack. More used to taking young groups of hikers up mountains than a coach load of oldies methinks.

Berlin Wall and Metekhi church

First stop in the old city is Europe Square. There is a piece of the Berlin Wall in front of the old walls here, presented as a gift to the Georgian PM by the German government, and placed here, with some ceremony, as a symbol of Georgia-German friendship in 2017. A symbol of independence from oppression. Saw a bit of Berlin wall in Tirana (See The Balkans, Part 5: Albania), when I was there. Gazing down upon it and us is Metekhi church, built in the 13th century, though much restored since. From the Berlin wall fragment, we head up towards it.

Rather good view from here down onto the bridge straddling the river Mtkvari, upon the banks of which Tbilisi was built. Vakhtang Gorgasali it was, who is credited as being the founder of Tbilisi, constructing his palace here in the 5th century. His equestrian statue gazes over the river here too. From this viewpoint we can also see the cable car taking tourists up to the top of Sololaki Ridge opposite, on top of which are the remains of the ancient Narikala fortress. Legend has it that King Vakhtang Gorgasali built Narikala fortress, later taken by the Persians, expanded variously by the Ummayads, and King David (IV) the Builder, who presided over the Kingdom of Georgia’s golden age in the late 11th/early 12th centuries, and others. Within are the remains of St Nicholas Church, which blew up whilst being used by the Soviets as an ammunition store. Not much was left of it and a new one was constructed atop the ruins in 1997.

After some contemplation we head back downwards from the church, cross the river and queue for the cable car. Six of us pile in each car and ascend swiftly to the top.

Step out and proceed up some steps and along a paved path to a twenty metre high shiny Soviet statue of Mother Georgia, made of aluminium and erected in 1997 to replace the first statue of her in this spot, which was built of wood. A symbol of Georgians’ national character, we are told, she holds a sword to deter enemies and a cup for wine to welcome friends.

On the other side of the area where she stands is a panorama over the botanical gardens with a lot of trees and a stream. Soothing. Further back, near the cable car station is a terrific view over Tbilisi. The guide points out the ‘White House’ where the PM once lived but it stands empty now, apparently, he says, as new PMs like to build themselves new residences. He doesn’t have much time for the present government, which is pro-Soviet. “Most of the population are against them”. Also from here we look over the Mtkvari River and the Peace Bridge, at one end of which is a weird structure that looks like two steel and glass tubes.

Opposite on the slope, a huge recently built cathedral with glittering golden dome, the main Orthodox Cathedral of Georgia, rises from the hill. Construction began in 1995 and it was consecrated on St George’s day in 2004, I understand. It is called Sameba, or Holy Trinity, Cathedral. It took a while before the building could be built, according to our guide. An Armenian cemetery had been located on the site. Caused a bit of upset.

Make our way back down the steps lined with souvenirs and pomegranates. Then descend back in the cable car to the old city. The tour resumes after an hour lunch break. Time passes. We walk to some old bath houses. Tbilisi takes its name from the hot baths here. The name means warm spot/place. The French novelist, Alexander Dumas, partook of its pleasures in the 19th century, as did the Russian poet, Alexander Pushkin, we are told. Jolly good. A minaret rises behind the baths. Our guide says that Muslims, Jews and Christians all live harmoniously together in Tbilisi. In fact, a building known as the ‘Peace Cathedral’ was opened in 2023, housing a mosque, synagogue and a church, where all groups can worship under the same roof.

Beyond the bath house domes is the gorgeous be-tiled facade of the Orbeliani Baths. Blue and cream tiles. Dogs like it here. Dozing on the paving stones. Thence we amble down a few streets passing the Great Synagogue, the largest in Georgia. Paintings by local artists are for sale on the walls close by. A lovely shiny black Mercedes advertises city tours, and an odd looking bronze figure, ‘Tamuda,’ a copy of a 7th century sculpture found in West Georgia, holds a hunting horn – for wine naturally.

Continue walking along to a Georgian Orthodox church, opposite which is another Soviet church, which has four Doric columns in front and is higher up. Quick nip inside the former, the 6th or 7th century Zion Cathedral of the Dormition of Tbilisi. Beautiful frescos inside and a relic of the cross of St Nino. Head down streets with ornate balconies and restaurants and bars lining each side.

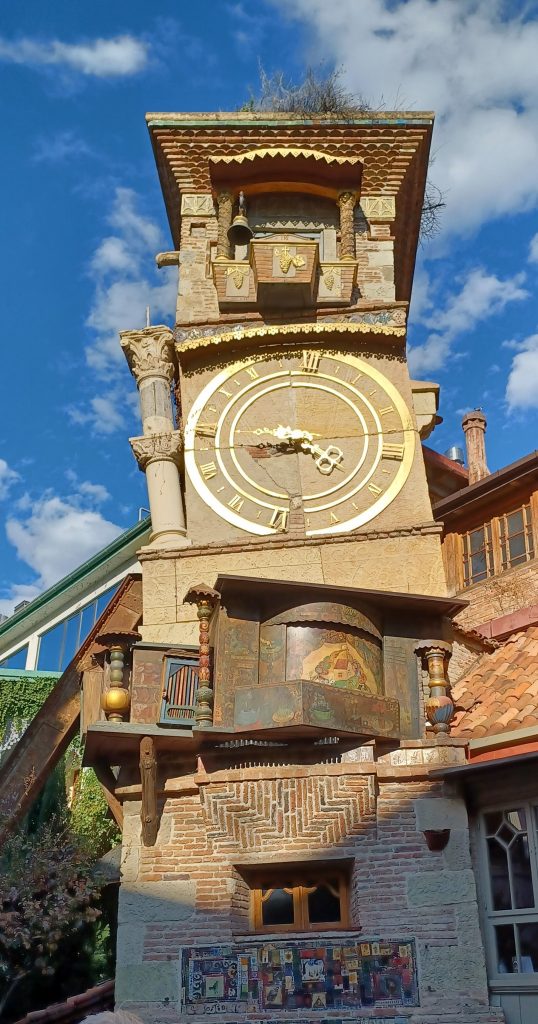

Arrive at the Peace Bridge, which we could see from the Narikala fortress. Pose on it. A guitarist serenades passers-by. Listen awhile. He is rather good. And boats ply up and down the river. A boat trip would be good to do wouldn’t it. No time. We sweep by a 6th century basilica, the oldest Orthodox church still standing in the city, then halt in front of a quirky leaning clock tower built on top of a puppet theatre. Higgledy piggledy. Supported by a steel beam.

There is a tiny clock on the clock tower, about one centimetre in diameter, which one can only make out if, having taken one’s photograph, one enlarges it afterwards. Clever. More churches. There are churches all over Tbilisi, including a Catholic church, Jewish synagogue, Juma mosque, the only one left in the old town and shared for services by Sunni and Shia, we are told. Figures of Dom Quixote and Sancho Panza appear on the pavement further on. Then we head uphill towards Freedom Square, past old Soviet buildings and ruins, towards the monument of St George and the dragon in the centre of the square.

Out to dinner in the un-glorious surroundings of our rather decent hotel with its large glass frontage and helpful doormen. Actually there is an area of restaurants clustered nearby. Pick a suitable looking establishment. I opt for cauliflower steak in truffle sauce. That’s novel. Hmm. Delicious. With wine. Naturally. This is our final night in Tbilisi though. A quick flit for a fleeting impression. No more than that. The capital city of Georgia deserves much more time. Will have to return. But tomorrow we head for the hills.

Leave a Reply