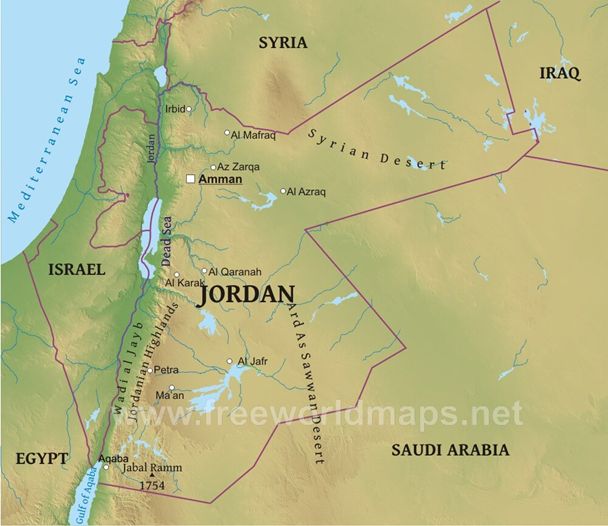

Jordan. The name has connotations. To some it means the Holy sites, for example, the River Jordan where Jesus was baptised by John the Baptist, and Mount Nebo from where Moses saw the Promised Land. To others it conjures up images of the rock cut tombs of the Rose City of Petra, built by the Nabataeans. Yet others have visions of Lawrence of Arabia in Arab dress, astride his camel, riding across the deserts in his quest to help the Arabs during the Arab revolt against the Turks during WWI. The Romans left their mark here, especially their city of Gerasa (present day Jerash); the Crusaders built forts, and the Umayyads built hunting lodges. In short, Jordan is a country with plenty of historical sites to see.

The first pre-requisite, or so I thought, was to obtain a visa to enter the country. I bought one online. Enterprising of me. Until I realised that I had paid more than twice as much for that particular pleasure as I would have, had I purchased on arrival. A representative from the tour company was there to help us do just that in fact. Never mind. All part of life’s rich pattern. A Jordan pass would also have been handy – and cheaper. This gives the holder not only a visa but also easy entry to most of the ancient sites. Good job it was winter with fewer visitors, otherwise I may have been queuing for some time at ticket offices. The hotel in Amman was adequate, although wine with dinner would have been welcome. I did not necessarily expect to be served alcohol in a Muslim country, though sometimes hotels in capital cities provide. Wi-Fi worked well though. One cannot have everything.

Despite this perhaps unpromising start, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is all fascinating. I toured around the country with a couple of others in a private car with driver, an affable would-be guide, with imperfect English. It was the beginning of February and winter had just begun, unseasonably late, according to our driver. Not the best time of the year to visit but one takes one’s opportunities when one can. Anyway, I tell myself, it is often so much better to tour out of season. One just has to dress in warm clothes and expect to be cold.

Amman

A trip round Amman was first on the itinerary. There are a couple of ancient sites of interest in the city plus an enormous fairly recently built blue mosque, named after King Abdullah I, who negotiated the then Transjordan’s independence from Britain in 1946. The mosque has a splendid dome of blue mosaics.

On Amman’s highest hill is the citadel, once named Rabbat Ammon after the Kingdom of the Ammonites in about 1200 BC, then renamed ‘Philadelphia’ by the Greeks. This means ‘city of brotherly love’. Who knew? That is one of the great bonuses of travelling: always learning something new. When the Romans took over in the first century, they built a huge temple on the citadel’s highest point, which they dedicated to Hercules. Scattered upon the ground amongst the remains of old columns and capitals, are fragments of Hercules’ once gigantic statue, including a huge chunk of three fingers. I note that one of the fingers even has a bit of nail left.

From the temple we look down on the Roman theatre, now surrounded by pale yellow and cream coloured modern blocks, residences of some of the four million inhabitants of modern Amman. The other main site on the citadel is the palace built by the Umayyads in about 720 AD. This was built over a Byzantine church and so its entrance hall is in the shape of a cross. We go in. A high impressive domed roof (restored) greets us, and a courtyard in front with stumps of columns. The building was destroyed by an earthquake in 749 AD, which also did for other cities at that time, such as Roman Gerasa.

Our driver beckons and off we go, stopping briefly at the well preserved Roman theatre in front of which a guard sits yawning on the wall. A tour group takes some group photos, while others take quick selfies in front of it before leaving. It is cold. We head for a large touristy shop where some female artisans are making tiles with mosaic patterns of pomegranates on them. The pomegranate ‒ a symbol of fertility apparently ‒ makes up about 10 % of all crops here in Jordan, I am told, and grows well in dry areas, which is just as well as Jordan has a water shortage. No shortage of rain today, it has to be said.

Jerash

Anyway, we imbibe a hot drink in the café here and the driver, draining his coffee cup, proclaims “and now we go to Jerash”. This should be interesting. I had never heard of this Roman city before booking the trip, so needed to read up about it. It was once situated on an ancient trade route and actually founded during the Hellenistic period but the Romans put it on the map, as it were. It covers a huge area. Not for nothing is it sometimes referred to as ‘The Pompeii of Asia’. We arrive and are given two hours to explore.

The rain ceases as I pass under the triumphal Hadrian’s Arch, built to celebrate the visit of the emperor Hadrian in 129 AD. Hadrian, as no doubt readers will know, built the wall across the north of England in 122 AD.

A colonnaded street, the ‘Cardo Maximus,’ paved with limestone slabs, proceeds from the Arch, and I head along it to explore the temples, theatres, hippodrome and baths. The rain may have gone and the brooding clouds soon lift but much water remains in the deep chariot ruts in the road and over the flat grassy expanse of the hippodrome. Chariot races were once held in the hippodrome. The signpost tells me it was the smallest one in the Roman Empire, although it claims to have seated 17,000 spectators.

I resume my stride along the Cardo Maximus and reach the large well preserved oval shaped forum surrounded by columns with Ionic capitals. Ionic capitals are the ones with a kind of spiral or scroll decoration each side. From the forum the long straight street continues to the north gate. As I bumble along the massive slabs betwixt which are bits of greenery, I come to the Nymphaeum, a large ornamental fountain, which once supplied the water to the public. It is decorated with columns and capitals along with a couple of weathered lions’ heads, which would have spouted water. In front is a giant stone bowl made of pink granite. I touch it. It is smooth and cold.

Up a slope near the north gate, the curved stone wall of the north theatre appears. I enter under an arched doorway to look down upon the semi-circular stage. Behind the rows of seats there are niches, which would have held statues. Scallop shells are carved into them. The signboard tells me the theatre was built in the second century but was abandoned, then occupied during the Umayyad period (661-750 AD) by potters. Like the rest of Jerash (and Amman) the theatre was ruined by the earthquake of 749 AD, but is now restored.

There are remains of bleached pediments, many with flowers and patterns carved onto them, columns and walls scattered everywhere in Jerash amidst the puddles. As I wander through the ruins of the yellowish brown stone temple of Artemis, patron goddess of the city, I meet a Columbian tourist. Said Columbian has a very large camera. We chat. He is very enthusiastic about the ruins and it appears that he has several days to explore them. “I will go to Petra another time, maybe next year,” he says, as he has not enough time on this visit. In contrast, we are scheduled to travel to Petra later today and view this famous city in the space of a morning. Hmmm. There is a lot more to see here in Jerash and not much time left to see it, but I am cold. I head speedily toward the Jerash rest house and restaurant. The temple of Zeus towers above its open terrace upon which are placed blue, green and orange plastic chairs, but it is too cold to sit outside. I cradle my coffee cup in my hands and gradually warm up.

Exploration resumes and I enter the ruins of the sizeable 5th century cathedral, which may have been built upon the Roman sanctuary dedicated to the god of wine, Bacchus. The builders probably pilfered the stones from the temple of Zeus as their building material. It often seems to be the case that incoming civilisations build their great buildings on top of other significant sites from the past. This is why archaeologists have such fun. Dig under one temple and they often find another below it, and another below that. Anyway, why quarry more stone when there is plenty to use locally.

On the way back to Hadrian’s Arch, I nip into another theatre, the south theatre, where one or two visitors are testing the acoustics with loud voices. I see the mosaic floor of a Byzantine church, which has an inscription in Greek and other scripts near the altar. There are other chapels in Jerash too, as well as mosques, which were built after the Umayyads took over. The whole city is surrounded by walls. One could spend many days here, though preferably in spring.

Petra

We are on the King’s Highway, part of the same ancient trade route on which Jerash is situated and only 300 kilometres from Petra. Once upon a time this was the route followed by the Israelites, the Nabataeans, the Ottoman Turks, Lawrence and the Arabs, pilgrims of various religions, and the list goes on. Somewhere we get onto the Desert Highway, which is straighter and quicker than the King’s Highway.

There are many trucks travelling this dual carriageway which leads south towards Aqaba and Saudi Arabia. It is a bit windswept and there is quite some sandstorm blowing, which reduces visibility. The windscreen wipers are on to try to clear the sand away. I am in the front seat peering ahead. “The road was closed last week,” our driver says. “Lot of sand”. “Not possible to pass”. One or two men are walking by the roadside, their bright scarves covering their heads and the wind buffeting their long robes. Rather them than me, I think. We pass many settlements of low houses, sand blowing everywhere. A stray dog stands mournful in a doorway.

Fortunately, we pass through the sandstorm and continue south until we eventually turn off the Desert Highway towards Petra. It is close to sunset. The rock formations become increasingly weird, gnarled and pink. The rocks are sandstone, which is easily eroded into these crazy shapes. The views are spectacular as we descend the steep road into the tourist town of Wadi Musa. “It means ‘Valley of Moses’”, our driver informs us. It is here where Moses is supposed to have struck a rock with his staff and water poured out of it. The ‘ain Musa’ or Moses spring was used by the Nabataeans, who constructed water channels all the way down the long narrow ‘siq’, to their city of Petra.

It is cold. The town is over 4000 feet above sea level in the middle of the mountains of south Jordan. Our hotel, the ‘Petra Moon’, is pink. The bed in the room has a towel on it folded in the shape of a swan – reminiscent of that Nile cruise ship in Egypt (see Egypt, part 1), where towels were folded in monkey shapes. Staff are welcoming and it is warm inside. And the food is good. Still no wine.

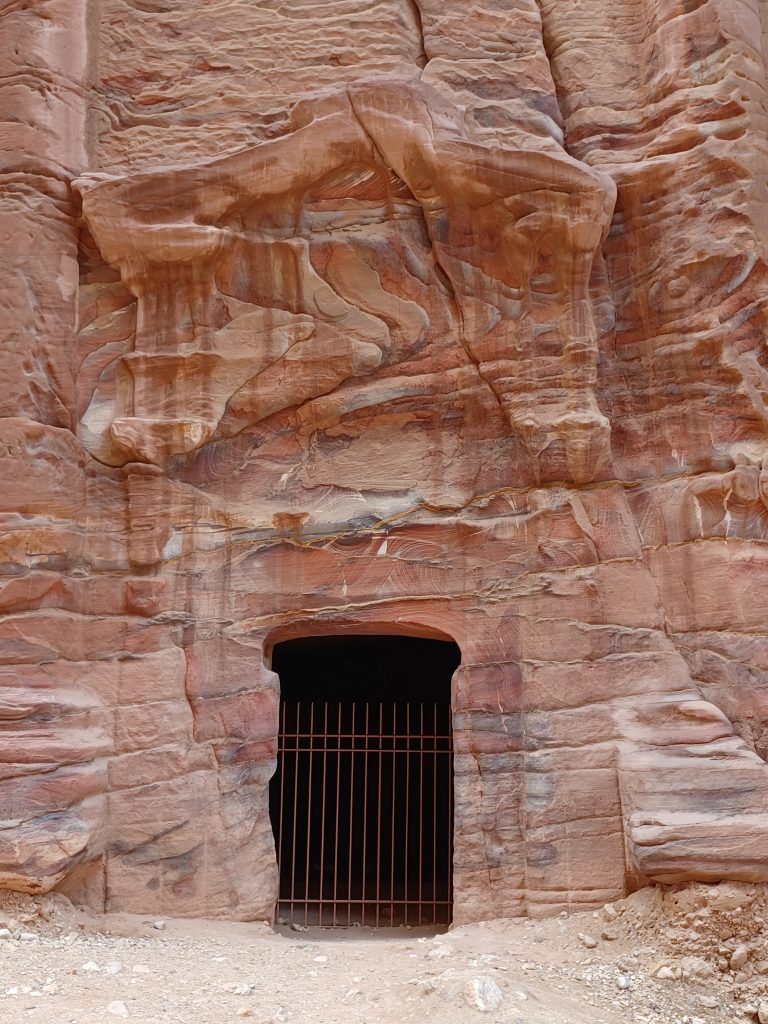

Early in the morning we are up and ready to visit ancient Petra, the capital city of the Nabataeans from about 100 BC. As many as 20,000 people may have lived here, enabled so to do because of the water supply. The city suffered a major earthquake in 363 AD and it is thought that this damaged the water supply system which contributed to its ultimate abandonment. It was not until 1812, when the city was rediscovered by a Swiss explorer named Johannes Burckhardt, that it was made known to the world. It is now a UNESCO world heritage site and was named as one of the New Seven Wonders of the World in 2007.

A local guide is provided. It is 0800. Our driver reminds us to be back at the gate by 1200. As we pass through the ticket office and souvenir shops, I spot racks full of gloves and other woollen items for sale to those tourists unprepared for the cold weather. I buy gloves. There is a biting wind as we follow our guide down the wide stony path. At least it is not raining. I had read that there was a flash flood here a few weeks before our visit. Despite the cold, there are quite a few tourists heading down the slope. I wonder what it is like in high season. It must be packed. Bedouin lie in wait with horses for hire to transport reluctant walkers. Nobody seems tempted. The horses’ saddles are draped with brightly coloured rugs.

Our guide, an earnest young man, is anxious to provide as much information as possible as we pass intriguing sculptures in the rocks. Much as I am interested, I wish he would get on with it. It is hard to focus when the wind slices through one’s five layers of clothing. We enter a small covered booth selling frankincense, among other things, and, as it is warm inside, I take time to handle said frankincense and sniff its spicy rich fragrance. Incense is a pale yellow resin, which forms on the branches of trees of the Boswellia genus and is harvested by scraping it off. It was used in rituals among many early peoples, such as the Egyptians, as it is today in, for example, Christian churches and Hindu temples. Associated with the gods it dispels evil spirits. And evil smells.

It is not surprising that frankincense was one of the gifts from the wise men to the infant Jesus as it was very valuable. Petra was the centre of the trade with Egypt, India, Greece and more. And the Nabataeans took advantage of their position by putting a high tax on goods passing through. The city grew rich, and attracted envious neighbours. And, although they managed to fend off incursions by the Greeks and others, the Nabataeans were unable to withstand the Romans who, under the emperor, Trajan, annexed the city in 106 AD.

We continue down the siq, the narrow gorge, ancient water channels on each side. Our guide points out the remains of a ceramic pipe in one of them. “They were very skilled engineers,” he tells us. “They built dams to collect water too.” As the area only has a few days of rain per year, this supply would last through the summer droughts. They also built secret reservoirs in the sandstone rock, which they lined with non-porous material. This water supply enabled them to ride out most sieges until the Romans came along.

The gorge gets narrower and narrower with its sheer towering walls almost closing together way above us. Some birds are making loud whistling noises high up on the steep cliffs. They are glossy black with a streak of orange on the wing ‒ Tristram’s starlings, according to my bird book, and are well adapted to the desert climate. Sometimes called ‘Dead Sea Starlings’, apparently.

Eventually, after over a kilometre walk, we get a glimpse of the famous ‘Treasury’ which, I gather, was built as a mausoleum for the King of Petra, and the gorge opens out into a large space to reveal the striking façade of this building. Sculpted from the soft red sandstone, it is decorated with Corinthian capitals – these have carved acanthus leaves on them ‒ atop columns, and an ornate pediment. “During their trading expeditions, the Nabataeans saw many Greek buildings,” our guide explains, “and this influenced the architecture in Petra.” The Greeks, of course, were, in turn, influenced by Egyptian buildings. A ray of sun is shining upon the Treasury. In front are two or three camels lolling on the sand and cameras are snapping everywhere.

I queue for the ladies outside a small building. It is a long queue. The gents’ loos have no queue. An elderly Bedouin is outside the gents keeping watch. He allows one lady to go in, whereupon half of the ladies’ queue migrates to the gents. Said Bedouin receives many Jordanian pounds in tips from relieved ladies. “Shokran!” Thank you.

Petra is inhabited only by a few Bdoul Bedouin, who claim descent from the Nabataeans, and who live in caves as their ancestors once did, tending herds of goats and sheep away from the crowds of tourists. Our guide tells us that most of the Bdoul were rehoused by the Government in buildings in a village nearby, as Petra became a major tourist attraction. Some offer donkey and camel rides, or sell souvenirs and refreshments.

We continue downhill along the ‘Street of Façades’ where large tombs are carved in the cliffs. The colours of the rocks are extraordinary with creamy whites and pinks and rusty reds in buckled layers. We pass the theatre, carved from the rock, and continue along the colonnaded street, which was created by the Nabataeans and rebuilt by the Romans. “This was the main shopping street,” we are told.

At the Great Temple of Petra our guide leaves us. Full of admiration for his extensive knowledge we tip him handsomely for the hour and a half tour. There is little time to explore further afield though, the 12 o’clock deadline looming. The way back of course is uphill. But first, I spend a genial few minutes in the brightly varnished ‘Nabataean Restaurant,’ a very enticing watering hole with warm smells of caffeine wafting out of it. Sandstone cliffs rear up behind and a little terrace with a few tables and chairs laid out on it sits in front with a couple of random palm trees. The sun has at last penetrated the cloud and is warming up the ancient city and its visitors. It is pleasant sitting here, one’s face in the sun. In the distance are the pinkish cliffs within which are the four Royal Tombs. A Bedouin in his long white robe – called a ‘thoab’ – and red and white chequered head covering – called a keffiyeh – walks by. Most Bedouin men here seem to wear these cloths on their heads to protect them from the elements – be it sun, sand storms or snow. A donkey wanders past with its foal in tow.

After coffee I ascend the ancient steps to the Great Temple, which is a mass of ruins. It is being restored by Brown University, USA, whose archaeologists began excavating here in 1993. Scattered over the site are many cylindrical shaped stones. They look like mill wheels. Some of them seem to have been reassembled into columns. Hexagonal paving slabs of sandstone in pinks and whites cover a part of the floor, which has columns all around it. The temple is the largest free-standing building so far excavated and would have been nineteen metres high, according to the signpost, thus towering above the colonnaded street. Most of the other buildings in Petra are cut from the rock. The once splendid houses and gardens, thought to have been here, would have been destroyed in the earthquakes.

Further up the street, nine men dressed as soldiers from the Nabataean cohort of the Roman Army are marching in formation to a drum beat. Shouting orders, the commander marches ahead of two lines of four men wearing khaki with shiny helmets and ear pieces, shield, sword and sandals. They must have freezing feet. Afterwards, they chat to tourists and pose for photographs.

I pass the ‘Royal Tomb Gift Shop’, where there are garments hanging up for sale and vases and other tourist trinkets. There are a few people frequenting the shop but nobody purchasing ice cream in the adjacent café. The Bedouin are not doing much business in the cold weather. The Jordanian flag flies in the stiff breeze atop the shop. The flag, a tricolour of horizontal black, white and green stripes with a red chevron with white star in the middle, in the hoist, is based on the flag of the Arab Revolt against the Ottomans in 1916, I understand. A man rides by on a camel. He is leading another camel saddled up and ready for an eager tourist to pay for a ride. “You like to ride?” The camel leers at me. An unpleasant haughty look. “No thank you”. Behind him, two Bedouin boys on donkeys trot by, grinning. “You want to ride?” I wave but decline.

It takes a while to stride quickly up the siq. I ponder whether to hire a horse. I have broken a bone or two in the past through falling off them. Perhaps not then, but I could have done with a ride. Our driver hails me as, out of breath, I reach the exit. We lunch in a characterful restaurant in Wadi Musa. The walls and floor are stone, the wooden benches have colourful soft seats and it is warm. The buffet is stupendous, with heaps of meats, vegetables and salads, washed down with tea. A suitable ending to our chilly time in the ancient Nabataean capital.

Leave a Reply