Sometimes, the business of deciding which country to visit next can become somewhat taxing. After all, there are at least 100 of them on my list. I have not yet resorted to sticking a pin in my world map at random, rather I try to prioritise those which pique my interest most and, of course, which are currently within my means. Thoughts have now turned to the ancient classical civilisations, their art and architecture, playwrights and philosophers. Having at one time being a student of Archaeology, one might think I would have visited Greece before but, apart from a fleeting sail to the island of Corfu, I have neglected the whole of mainland Greece in my travels hitherto. The country contains some splendid ancient sites, including theatres, temples and tombs in some wild and isolated spots on the Peloponnese peninsula. Thus, the tour I eventually chose was to include probably the most famous of these, but also monasteries on massive rock outcrops, a onetime capital, museums and, of course, Athens.

There were only six of us on the tour. This is because, no doubt, it was February. Really, it is a no brainer to visit off season. The temperature was about 18 – 20 degrees, dry and mostly sunny, yet very few visitors were wandering about the ancient ruins. We had most of them practically to ourselves, avoiding the huge crowds and heat of the Summer.

The Acropolis

It is day one and the others in the group are not here for some reason so, for a morning tour of the Acropolis of Athens, I have the young female guide all to myself. One of those enthusiastically erudite types with spring in step and dark hair swinging around her shoulders. We ascend the steepish steps to the entrance. Poised to enter the ancient citadel, she gestures to the right side of the massive ceremonial gate (the Propylaia), where the creamish stone temple of Athena Nike ‒ Giver of Victory ‒ overlooks us. I suppose the name ‘Nike’ inspired the sportswear brand. “This is the earliest Ionic temple of the Acropolis”, she informs me.

The Parthenon

Once through the gate, there, dominating this rocky crag, is the Parthenon, iconic temple and symbol of Ancient Greece with its fluted marble columns and friezes. Whilst it is visible from anywhere you are in Athens, one can also see the sweeping sprawl of the city, with its five million population, from this vantage point. It is situated in a basin with a further spectacular seven hills around it. In summer it can get very hot and pollution fills the basin but today the air is fresh and visibility good.

The guide delivers her spiel about the history, art and architecture of this building. The Parthenon, she tells me, was built in the 5th century BC and the name means ‘maiden’ or ‘virgin’. It was dedicated to Athena, protector of Athens, warrior goddess, also associated with wisdom and often depicted together with an owl. The buildings here, having been sacked by the Persians in 480 BC, were reconstructed by the architect and celebrated sculptor, Phidias, during the Golden Age, or Classical Period, under the famous statesman, Pericles. “This is where democracy was founded and the famous philosophers, Socrates and Plato and Aristotle, walked about”. It was designated a UNESCO heritage site in 1987.

I count eight marble columns at each end of the Parthenon and seventeen down the sides. Quite a bit of scaffolding is stacked up around them at the moment, and bits of stone and brick and machinery lie about. Clearly some restoration going on. Even so, atop the columns one can see the Doric capitals. These are undecorated square slabs, quite different to the Ionic and Corinthian capitals with their carved scroll shapes and acanthus leaves respectively. Earlier I am told.

Above the capitals are what are called ‘metopes,’ square marble sections with a pair of mythical characters sculpted in each. There were once 92 of them. One of them, the only one remaining on one side, depicts a fight between a centaur and a Lapith (mythical man from Thessaly). “Some of the metopes were destroyed by early Christians”, says my guide. “They used the temple as a church”. Centuries later the Ottomans used it as a mosque, then stored gunpowder in it, which exploded during the siege by the Venetians in 1687.

Some of these metopes and almost half of the magnificent frieze that wrapped around the Parthenon, as well as on other buildings on the Acropolis, were removed by Lord Elgin’s men in the early 19th century and these, the Elgin Marbles, are still on display in the British Museum, much to the chagrin of my guide. “We hope one day to get them back here where they belong.” It is a moot point as to whether Lord Elgin actually stole the sculptures in that the authorities in the Ottoman empire, which then ruled Greece, supposedly gave him permission to remove them while he was the British Ambassador. The poet, Lord Byron, who lived in Greece at the time and greatly revered the classical Greek world, condemned Lord Elgin for shipping the Parthenon friezes to Britain. In his poem, ‘Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage’ (1812), he wrote bitterly:

Dull is the eye that will not weep to see

Thy walls defaced, thy mouldering shrines removed

By British hands, which it had best behoved

To guard those relics ne’er to be restored.

Curst be the hour when from their isle they roved,

And once again thy hapless bosom gored,

And snatch’d thy shrinking gods to northern climes abhorred!

When Greece finally regained its independence under the Treaty of Constantinople in 1832, a campaign to restore the marbles was launched, but they remain in the British Museum and the dispute with the UK continues. Later, in the Acropolis Museum, I see replicas of the original frieze, which depicts a procession of Athenians and horses in honour of Athena. Inside the Parthenon would have been the once massive statue of the goddess Athena, made of gold and ivory, sculpted by Phidias. “Nobody is quite sure what happened to it. Maybe the Christians removed it”.

The Erechtheion

We continue walking across the uneven stony ground to view the Erechtheion, a temple dedicated both to Athena and Poseidon, God of the Sea. The porch is supported by six female figures, the Caryatids (maidens of Caryae), who pose as columns over seven feet high holding up the roof. One of the original Caryatids was removed by Lord Elgin, the others are in the Acropolis museum, while the ones here are replicas. They each would have been painted a different colour I am told, but are faded to the original creamy white marble. Picture their drapes in red, gold, blue, green. Fantastic they must have looked in ancient times.

The Parthenon itself may also have been painted in bright colours, according to some archaeologists, but a debate about this is ongoing.

Odeon of Herodes Atticus

My guide leads me along a path below the citadel whence we peer down on a stunning Roman theatre, the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, its marble stage paved with black and white diagonal shapes. Behind it rises a three storey stone wall. “It had a wooden roof once, made from the cedars of Lebanon”, she tells me. “The theatre was a gift from the Roman Emperor, Herodes Atticus, to the city” she says, during the time that Greece was under Roman control. “We call it the Herodeon. The great Maria Callas performed here, Luciano Pavorotti, Nana Mouskouri”.

The theatre was fully restored in the 1950s and is very much in use today for plays and concerts. Imagine being one of the 5000 or so spectators witnessing such a performance, or a symphony orchestra on a summer’s eve, I muse.

Theatre of Dionysus

Passing remains of columns and stone walls, we continue down the dusty track past another theatre ‒ of Dionysus ‒ with its backdrop of trees. This is a Greek theatre, dedicated to the God of Wine, and predates the Herodeon by 500 years or more. “Ancient Athens was the birthplace for Greek theatre”, the guide informs me and “This is the oldest theatre in Greece”. It housed well over 15,000 spectators and plays written by important playwrights, such as Euripides and Aeschylus, were performed here. After performances offerings would have been made to Dionysus.

Time for refreshment in one of the many cafés below. Lazing back in a chair, I digest all, well some of, the information imparted, with a Greek coffee. Splendid view looking up towards the acropolis. Sun has emerged too.

Ancient Agora of Athens

Temple of Hephaestus

I mosey along to the Greek agora now. During ancient times, the agora — market place — was the main meeting place for the population to socialise, trade and talk politics. A band is entertaining the populace near the entrance to the site. Lively traditional music featuring a bouzouki, some sort of tambourine and a violin. I delay my exploration. Grab an outside table in a nearby eatery for a spot of lunch: moussaka and a glass of Greek wine. Soak up the music and the sunshine while perusing my guide book. My plan is to head first to the fifth century BC marble Temple of Hephaestus. Hephaestus, I learn, was the Greek God of fire, a blacksmith and craftsman, who made military items for the gods on Mount Olympus, for example the winged helmet and sandals for Hermes, the messenger god (equivalent to the Roman god, Mercury).

An incredibly well preserved temple this is, its roof intact atop its Doric columns and capitals, and its friezes with centaurs and other mythical animals. Lord Elgin missed these. The metopes on the outside are also intact, the ten on the façade depicting the labours of Hercules (the Greeks called him Herakles). The temple sits stately amongst low hedges and pathways. It was used as a church in the 7th century (the church of St George), as was the Parthenon, and later a burial place for Protestants, according to the information board, as well as for lovers of Greek culture or ‘Philhellenes’, Europeans who died in the Greek War of Independence in 1821.

Thence to wander around the ancient agora in the footsteps of the philosophers. St Paul was here too, 500 years later, spreading the Christian message. I inspect the remains of columns and walls, where there would once have been houses on streets and squares with lively markets, trying to imagine life as it was in the Golden Age. I happen upon a more modern artwork, two bronze statues featuring ‘An encounter’ between Socrates and Confucius. This artwork was created by Wu Weishan after the Covid-19 pandemic showing the two philosophers exchanging ideas. A fitting venue for it in this ancient city state. A lone sparrow hops about the stones.

Syntagma Square

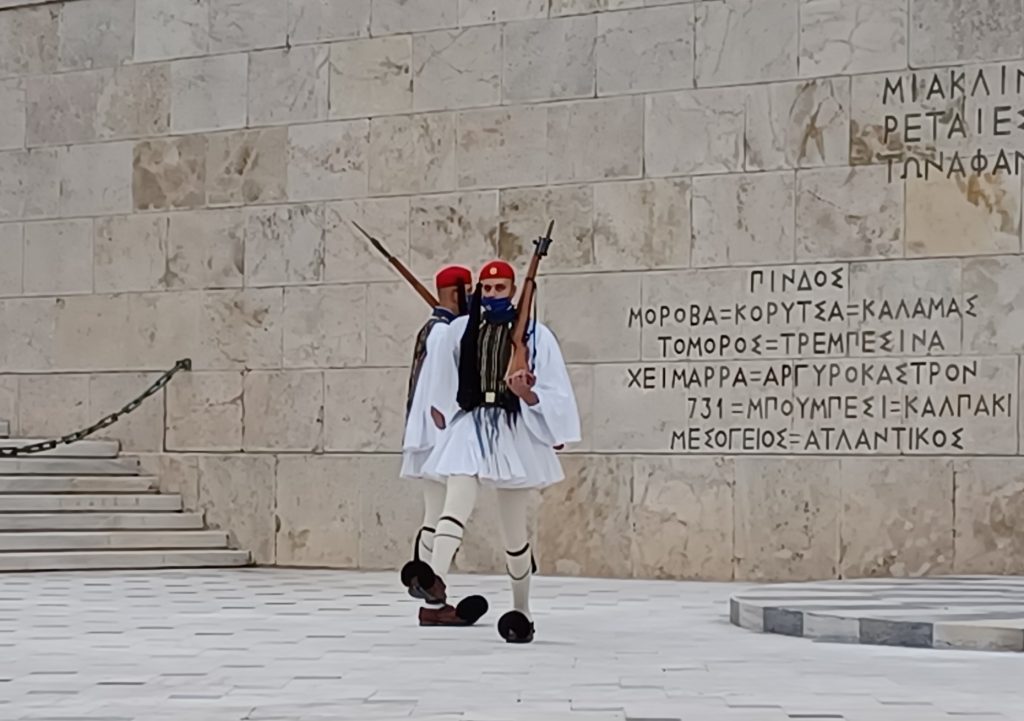

As I roam around the city I find myself in Syntagma (Constitution) Square, the heart of Athens, by the old Royal Palace. The Palace is now the parliament building and is dedicated to all those Greeks who have lost their lives in wars. At the foot of the Palace is the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in front of which Greek guards in short white pleated skirts, red berets and shoes with black pom poms on them, are parading up and down with their rifles (The blue masks are an unfortunate addition due to the lurking presence of Covid-19). Named the ‘Evzones’, this guards regiment was founded during the Greek War of Independence in 1824. I watch the changing of the guard take place. The guards raise their legs high with a kind of slow dignity. Later, as I stroll down a side street I encounter two of them and enquire about their uniforms. The skirts, I am told, have four hundred pleats, which represent the number of years the Greeks were ruled by the Ottomans.

Exploration over for today, I head for the hotel to meet the tour group members and our guide for the coming week.

Leave a Reply