The Nile Cruise

The returnees from Abu Simbel are late. Thus I partake of a placid luncheon, the sole person at the big broad table, and reflect upon my lazy flit around Aswan. But, eventually, noisy people appear, engines start up and the long awaited river cruise begins. Heading north now, we motor between the long low banks of the Nile bejewelled with deciduous trees and palms, the odd felucca moored at the river’s edge, and a few birds paddling about. I am on deck chatting to some of the group about their tour to Abu Simbel. Some of the others have chosen to catch up on sleep in their cabins and miss this glorious afternoon.

Kom Ombo

As the sun gradually goes down, the temple of Kom Ombo is spied, lit up by floodlights, by the riverbank. Other identical ships are ahead of us vying with each other to get the first spot alongside the quay.

One, that was following us, puts on a spurt and overtakes. By the time we get there three ships are already rafted up, the striking Kom Ombo temple rising up behind them.

Kom Ombo is an unusual double temple built for two gods, each with its own entrance. One part of the temple was dedicated to Horus, while the other part was dedicated to the crocodile god, Sobek. We visit the museum dedicated to crocodiles, which were mummified here. It contains some of the 300 mummies which were found in Kom Ombo. Long and thin and black and grisly. Within the temple itself is carved a scene on a wall featuring surgical instruments, such as scalpels and forceps. Kom Ombo, it seems, was a place of healing.

The ship continues down the Nile through the night and, having breakfasted, I head on deck armed with my binoculars to see what I can see. The banks pass blissfully by; a pastoral peaceful landscape with the odd egret fluttering about. As we slowly approach the large lock at Esna, a couple of Egyptians in a blue rowing boat with blue oars and a striped carpet on the floor come alongside and attach their craft to the ship with ropes. They shout at the assembled multitude gazing down at them and display various items for sale. One of them holds up a yellow wall hanging portraying the three pyramids of Giza with three camels in front of them. There is much bartering back and forth, parcels of merchandise being thrown on to the deck for would-be purchasers to inspect and cash thrown back again into the rowing boat if all is satisfactory. This goes on for some while until the ship enters the lock and they slip away in the ship’s wake. We arrive at Luxor, where some of the major archaeological sites of Egypt await us.

Luxor

Karnak

First we head off to the magnificent temple of Karnak, dedicated to the god Amun, on Luxor’s eastern bank.

Karnak and all the other temples are situated on the east side of the Nile, whence the sun rises, while the tombs of the pharaohs are on the west side of the river where the sun sets. Karnak is rather overwhelming. It was the ancient capital of Egypt for over 1500 years from the Middle Kingdom to the Ptolomaic and was built about a thousand years after the pyramids, in the fourteenth century BC. Full of colossal columns, carvings, paintings, obelisks and a sacred lake, there is also the mile and a half long avenue of sphinxes, which once connected Karnak temple to Luxor temple.

“Cleopatra VII”, she of Antony and Cleopatra fame, I hear, “was the last Ptolomaic ruler”. She renovated the avenue between about 50 and 30 AD.

“Each pharaoh, about thirty altogether,” we are told, “added to the temples that were built before”. “See here”, our guide points out, “that is the obelisk that Hatshepsut, the female pharaoh, erected.” Other examples include a hypostyle hall with 134 columns built by Seti I, and the third pylon built by Amenhotep III. Many courtyards and gates were added and/or altered. Sacred ceremonies would have been carried out inside. There are the remains of the ancient harbour also, with a ramp leading down to where the Nile once ran. On one of the walls is a relief with a list of many of the pharaohs that had ruled Egypt beginning with Sneferu, he who built the Bent and Red pyramids. Some names are destroyed. This list, nevertheless, has helped Egyptologists to piece together the chronology of the pharaohs.

Balloon over Luxor

Early the next morning is to be one of the main highlights of the trip, a balloon flight over Luxor. I heard that the first balloon company in Luxor was a British one, which began offering flights in 1988. Jolly good. We are woken up by the ship’s communication system long before dawn, and taken in a police convoy to the airfield where deflated hot air balloons are laid out across the ground. Upon receiving a signal from the authorities that all is well, a couple of dozen balloons are blown up in unison. There is much noise and activity. Groups in orderly rows stand waiting to file into the baskets at the appropriate time, the balloon pilots turn up the gas in the burners and off they float one after the other with the sunrise. Our turn comes. Our balloon is blue, yellow and white with the name of the company, ‘Sindbad’, standing out in large blue and red letters.

We stand in different sections of the basket so that the weight is balanced evenly. We ease off the ground and are soon floating over the Valley of the Kings, the Valley of the Queens, the Temple of Hatshepsut, and the Ramesseum. The latter is a huge temple complex dedicated to Ramesses the Great (II). The poet Shelley is said to have written his ‘Ozymandias’ based on the head and torso of Ramesses II (reigned 1279 – 1213 BC), which was found in this temple. It was removed from there and taken to the British museum. The poem is one of my favourites so here it is:

Ozymandias

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

(Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1792-1822)

We continue to drift across the dusty valleys pockmarked with tomb entrances, bright specks of other balloons like so many bubbles in the distance. The pilot is beaming. The occupants of the basket, wrapped up warmly in the cool air, rejoice. The green strip of vegetation by the Nile contrasts starkly with the dusty brown of the desert as the sun rises steadily. We observe the fleet of white minibuses lining the road, waiting to rush off in pursuit of their respective balloons in order to pick us up after the descent.

Some 40 minutes later, we drop softly landwards. Pure ecstasy. Crew from our minibus jump out and catch the ropes thrown to them, then peg the basket down. We clamber out. That was fantastic.

Temple of Hatshepsut

No time for coffee, as we head speedily for the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir-el Bahari. This temple is quite different to Karnak. It is a long building, much restored, with a long ramp between symmetrical halves. Steep cliffs rise behind.

Ascending the ramp, one is greeted by nine statues of the pharaoh in front of nine relatively short columns. There are many more columns but the pharaohs are missing. Hatshepsut was married to a sibling, in this case her half-brother Thutmose II, as was the usual practice with pharaohs, but he died and she ruled Egypt for about twenty years from about 1478 BC. After her death, all carvings and cartouches with her name on were erased by her successor, Thutmose III. She is depicted, however, in several places as a man, with beard. The nine statues of her portray her thus. Evidently female pharaohs were not considered suitable rulers, even though history shows that she reigned very effectively.

Valley of the Kings

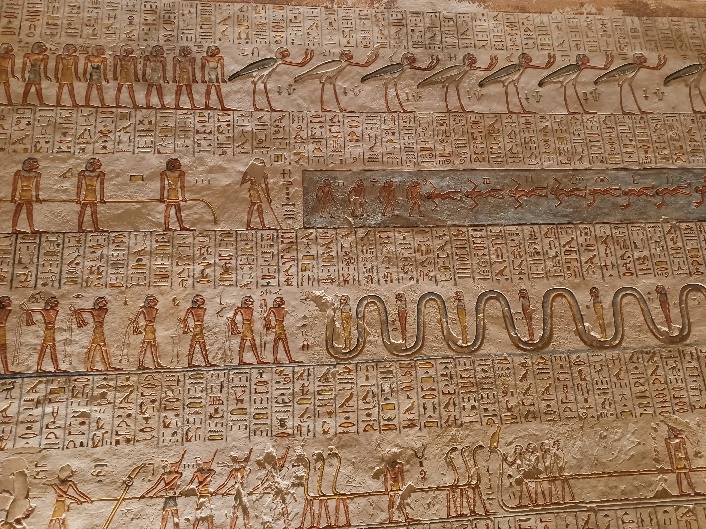

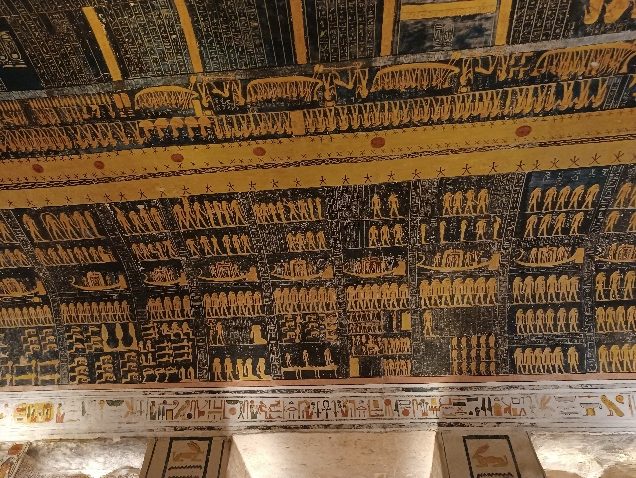

The Valley of the Kings, which we also surveyed from our balloon, is next up. From about 1550 BC, the pharaohs of the New Kingdom chose to be buried in tombs underground in the Valley of the Kings instead of in pyramids ‒ the custom of their ancestors of the 4th dynasty. I am particularly keen to see these tombs and, indeed, they have to be seen to be believed. The most highly decorated one that I visit is that of two of the sons of Ramesses II, that is, it was begun by Ramesses V and completed by Ramesses VI. The long entrance leading to the inner chamber is covered with paintings and hieroglyphs from floor to ceiling, in almost perfect condition.

In their original colours, such as blue, red and yellow, they feature gods, goddesses, humans, animals, fish, snakes, birds and boats.

The tomb would once have been full of gold and precious items. Sadly, tomb robbers broke into many of the tombs shortly after burial or, otherwise, ensuing pharaohs looted them themselves.

The tomb of Tutankhamun (who was often called King Tut) is not as splendid as this one. “It is not as beautiful because he died young and the tomb builders did not have sufficient years to build and decorate it”, we are told. The fact that it was found intact stuffed full of precious objects was because the entrance was very close to another tomb and it was overlooked. The robbers missed it, but the British archaeologist, Howard Carter, after systematic searching, found it in 1922. In the Egyptian museum in Cairo, the items from Tut’s tomb are displayed. I was to see them when we arrived in Cairo.

It is late afternoon and it is hot. The bus stops in front of an area where there are two colossal statues named, appropriately enough, the Colossi of Memnon; actually statues of Amenhotep III, grandfather of Tutankhamun. They stand at the entrance to his once grand funerary temple, the largest in ancient Thebes (present day Luxor).

We pile off to goggle at close quarters. Nothing much else is visible except the Colossi but archaeologists are hard at work digging behind them. It is odd to see these massive statues beside the road. Who knows what is yet to be discovered here? After taking hasty photographs, we pile back on the bus again for a visit to the Papyrus Museum.

Papyrus museum

This should be interesting. Papyrus was cultivated in the Nile delta, needing fresh water to grow, and its long stem was used for making paper. A graceful plant it is with its tall stem and spidery like green fronds hanging down from the tip, and it was very significant to the Egyptians, being a symbol of rebirth. I suppose that is why the columns in the hypostyle hall in Karnak and elsewhere imitate the papyrus marshes. A member of the museum staff demonstrates how the woody stem is cut into strips and these strips are laid across each other at right angles then pressed together and dried to form a writing surface. Ten or twenty of these sheets would be glued together to make a scroll and these were exported to Europe, e.g. Rome and Greece. Before parchment took over, papyrus was the standard writing material for centuries, the Dead Sea scrolls being a famous example.

We watch a couple of staff painting onto the paper after which, inevitably, we are encouraged to view the papyri for sale “specially for your group, at a good discount”. They have all sorts of decorations on them ‒ from Egyptian gods and goddesses, to boats, animals and signs of the zodiac. I buy some for family members and a young chap scribes their names upon them in hieroglyphs.

Unique gifts. I am well pleased with my purchases. But now we have to hasten back to the ship as Luxor temple is scheduled to be viewed in the floodlights after dinner.

Luxor Temple

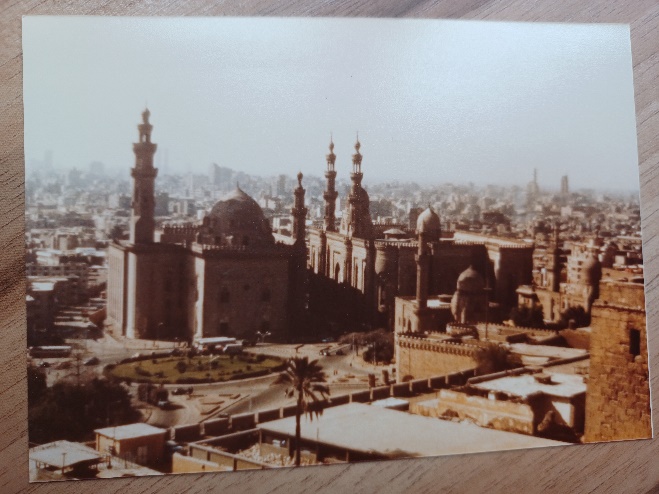

Luxor temple, also dedicated to the god, Amun, is likewise colossal. In front of it are six statues of Ramesses the Great, about half the height of the pylon (gateway), and one obelisk 80 feet high, also built by Ramesses, which rises even higher.

There was once another obelisk matching this one at the other side of the main pylon but it now graces the Place de la Concorde in Paris. Our guide laments that Mohammed Ali Pasha, whose tomb is inside his mosque built within Saladin’s citadel in Cairo, exchanged the obelisk for a ‘modern’ French clock, which has never worked. Nevertheless, it is a very attractive and large clock and sits atop the walls overlooking the courtyard of the mosque. London and New York also have one each of a pair of Egyptian obelisks quarried in Aswan: Cleopatra’s Needles, located on the bank of the Thames and Central Park respectively. But I digress. The temple contains a hall of columns built by Amenhotep III and completed by Tutankhamun after Amenhotep’s death. When the Romans came and Egypt became one of the provinces of the Roman empire, they converted Luxor temple and plastered and painted over much of Amenhotep’s decoration. The Arabs later ‒ in the 7th century ‒ built a mosque atop the temple walls.

It all looks splendid in the floodlights and, as we emerge, several dancers and performers are dressed up in ancient Egyptian garb ready to perform a show. Shame we will miss it. Talk about packing it all in to one day. Early balloon flight, then visits to all those tombs and temples. Too much to absorb. It was fleeting and fantastic but, should one wish to actually learn something about ancient Egyptian civilisation, one would need at least a good book, and time to read it, and some in-depth visits. I suspect that our tour was enough for most visitors though, just a flavour. Personally I would like to have had longer, but soon we were to leave the ship and head to the Red Sea Coast for a rest.

One of the main facts that was brought home to me about Egyptian civilisation was that it lasted about three thousand eight hundred years – measuring from the Early Dynastic Period to the end of the Roman Period – an incredibly long time. They were building huge stone monuments and cities while most Europeans were still hunter-gatherers. As was emphasised on more than one occasion, the Greeks, after conquering the Egyptians in 332 BC, were able to study their architecture, such as columns and capitals, and imitate it. They even assimilated the Egyptian Gods into their own pantheon. The Romans, later, did the same.

Hurghada

So I have seen the most famous Egyptian temples and tombs in a day and a half and now have two days to recover in the Red Sea resort of Hurghada. It is pleasant enough, even has Wi-Fi, but the winds are just a bit too strong to enjoy lazing on a sunbed and, anyway, I get bored so doing. A friend and I go off on one of those boats with glass sides to spy on fish and coral for which the Red Sea is famous.

The coral reefs close inshore here have become a bit battered with so many boats, at one time anchoring on the bottom helping destroy the reefs, before the authorities put a stop to it. However, we view some colourful fish, and a large ray. All worthwhile. Then comes a dip in the Red Sea. All part of the advertised adventure so one feels obliged to get in there and participate in the ‘fun’. It is mighty cold. I swim about a bit with flippers on and stick my head, wearing mask and snorkel, below the surface. Don’t see much though as the boat has stirred up bits of dust during its manoeuvres. An Egyptian lady lowers herself into the sea from the stern ladder covered from head to foot with all her long black clothes and head scarf. She has to cling to a life ring to avoid sinking under the weight of them.

We leave Hurghada at 0400 next morning. Say no more. The air conditioning in the bus is set so low that I put my woolly hat on and cover myself with a winter coat. As it grows light I can see the Red Sea on one side and the flickering desert the other and a huge wind farm in the distance. We stop for coffee in a large roadside establishment, I pay five Egyptian pounds to use the loo and we are on our way again. The aim is to reach Cairo in order to have a city tour this afternoon.

Cairo

I had been to Cairo years ago, during the same quick flit which included the camel ride at Giza, mentioned earlier. I remember going to the citadel and visiting the Mohammed Ali mosque (in which sits the French clock). So today, I again visit the aforementioned mosque high on top of the hill, its lower walls of alabaster shining white and its Turkish style minarets.

I take a photograph from the citadel looking down upon another mosque, the 14th century Mosque-Madrassa of Sultan Hassan, and, on returning home, find a photograph taken of the exact same view when I had visited all those years before. Funny that.

Treasures of Tutankhamun

From there to the superb Egyptian museum, with its pink neoclassical façade, where I see the treasures of Tutankhamun: his face mask, his chair with lion’s heads on the end of the arms and lion’s feet and his alabaster chest containing the canopic jars, in which his organs would have been placed. There is also a statue of him painted black – the symbol of the fertile soil of the Nile valley – with gold headdress, neck piece, kilt and sandals.

Chariots, mummies, papyrus scripts and all sorts of incredible objects are housed in the museum, but, as is usual, not enough time is allotted to peruse it all. (NB, King Tut’s treasures are now housed in the new Grand Egyptian Museum near Giza).

Garbage City and Coptic Cairo

Cairo is very large, polluted and chaotic. Taxis are cheap, however, so one can get transported the large distances across the city relatively comfortably, provided that one enjoys swerving across five lanes of honking traffic or, more likely, being at a standstill. Many buildings are unfinished, with reinforcing steel rods sticking up out of the brickwork in preparation for the next storey. And there is rubbish everywhere. We may tut-tut at the stray plastic bags along roadside verges in the UK but in Cairo this is taken to a whole new level. There are piles of garbage; there is even a ‘Garbage City’ here, where unenviable Coptic Christians sort, package up and recycle the tonnes of it piled in the streets, on bridges, on shaky trucks and on weary men’s backs.

Dollops of plastic are strewn to the four winds. As I wish to visit the Cave Church of St Simeon as an optional extra, we have to venture through the streets of Garbage City to get to it. There is no other route.

The Cave Church is situated within the mountain of Mokattam, said to have been moved by St Simeon to show his faith, and seats 2000 worshippers. On arrival, however, there is a funeral going on, so I hesitate before entering unobstrusively, camera in pocket, and merely stand at the back and keep quiet before once again barging through Garbage City and off to explore the Coptic quarter.

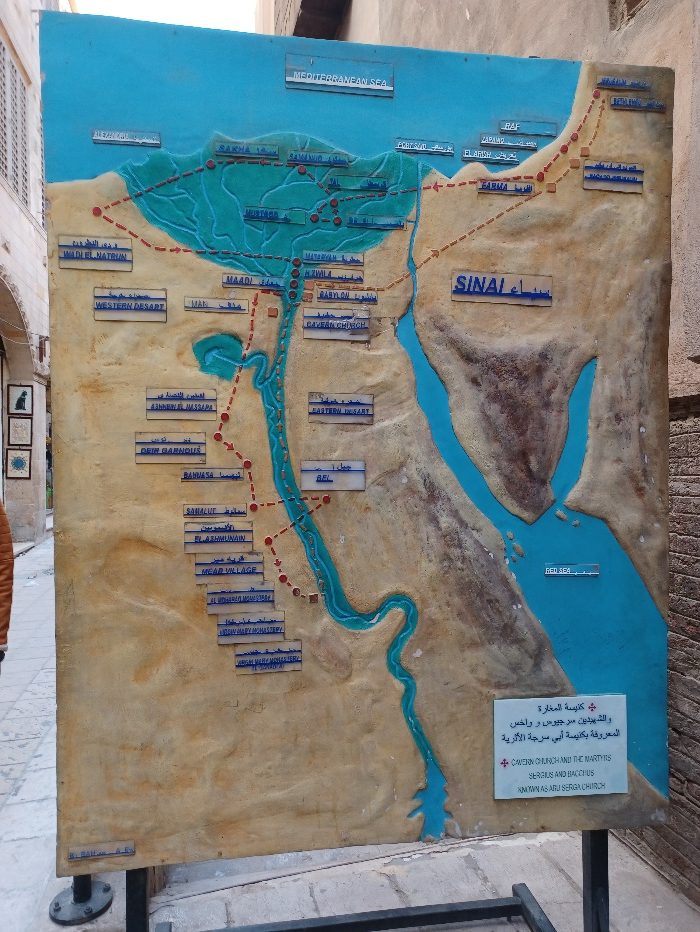

I know little about the Copts, except that I had learned that the second language on the Rosetta Stone was the basis for Coptic. In Coptic Cairo we visit the hanging church of the Virgin Mary, so-called because it sits atop the ruined Babylon fortress, a Roman structure built in 98 AD by Trajan. A hundred icons grace its walls. Much of this beautiful church is decorated with geometric shapes with both pointed and round arches. Afterwards, as we wander through the narrow streets thronging with people, we come across a large map on a board depicting the journey of the Holy family into Egypt.

We then enter the Cavern Church where they were supposed to have hidden from Herod the King, along with the Holy well from which they are said to have drunk.

Khan el Khalili

Our tour of Cairo ends with a visit to the old bazaar of Khan el Khalili with its maze of alleyways and souvenir stalls. Bombarded from all sides by those who wish me to sell me their exquisite ‒ or not so exquisite ‒ wares, I finally buy a pouffe of many colours after much bargaining. Then sit and sip tea in a café in the midst of it all as the long day wends to its weary close.

Cairo is fascinating – from its old quarter full of mosques and bazaars to its newer residential areas and museums. As with the rest of Egypt there is too much of interest to write about it all. Best go there yourself to get the feel of it, perhaps in a more leisurely fashion, and enjoy the craziness.

Leave a Reply