I am on a tour of Jordan. Waving adieu to the red sandstone city of Petra, we are driving south to the shimmering sands and rock formations of Wadi Rum, made famous by the film, Lawrence of Arabia. This is where the legendary T.E. Lawrence was encamped with the Arabs during the Arab revolt. This period of history and Lawrence’s role in it is described in the latter’s splendid book, ‘Seven Pillars of Wisdom’, first produced in 1926.

Hejaz Railway

We leave Wadi Musa via the same steep winding road with its stunning views over the mountains and re-join the Desert Highway. First stop is the Hejaz railway, where some refurbished carriages of the old Ottoman train sit isolated in the vast expanse of the desert. The railway line was supposed to link Istanbul with Mecca, while this bit of the line was used, among other things, to transport soldiers of the Ottoman empire. Although completed by 1908, it was, according to our driver, not appreciated by the local tribes, who were afraid that the railway would take away their livelihoods, i.e. camels would no longer be required for transport. “They took the wood for their fires”, he says (the sleepers, that is). Later, during World War I, Lawrence, together with Prince Faisal and his Arab guerrillas, ambushed the train and blew up the railway line many times. There are vivid scenes of these attacks in the wonderful film, directed by David Lean, ‘Lawrence of Arabia’.

It is a lot warmer here than in Petra. The old pale green wooden railway carriages sit tranquil under the blue sky, with the cheerful red Turkish flag with its white crescent moon and star, flying above them. The old steam engine is parked close by. The tracks disappear into the sand. It is not clear how far they now extend. After the war, when the Ottoman empire ceased to be, the railway was abandoned leaving this remote outpost to attract curious travellers. We clamber over the carriages.

From the railway, we drive across a sandy plain dotted with rock outcrops towards Hasan Zaweideh Bedouin camp. Situated under a steep sandstone cliff and fringed with palm trees, this is our base for the night. More romantic it may be to camp out in black tents round an open fire, but this suits me just fine. The chalet type accommodation is fabulous ‒ en suite with a heater on the wall.

Many travellers assemble for a late afternoon excursion and are soon boarding 4WD vehicles for a spin. There are tyre tracks mixed with camel hooves everywhere. Our young driver speeds across the red sands to the cheerful yells of the passengers sitting outside. I notice that a few of them are wearing those red and white keffiyeh on their heads. Looking the part. We stop at the place where Lawrence and Faisal were supposed to have encamped. Carvings of their faces are on a rock. Further on and all the vehicles stop to disgorge their passengers at the foot of a large rocky outcrop, which is smothered with soft sand, into which one’s feet sink. We all reach the top, some plodding up more slowly than others, I have to say, and peer round at the view. The landscape here, ostensibly, resembles that of Mars. And the Wadi Rum area has been used for several space sequences in films. Closer to the camp, we all perch on a rock waiting for the sun to dip down behind a jagged cliff, its red sinking rays poking through the gaps. Nobody speaks. It is quite surreal, like a Dali painting.

Before dinner I wander towards the cafeteria, where a buffet is being prepared. Distracted by the sound of music drifting out from a long low building, I change direction and venture inside. The interior is lined with stripy woven rugs and tapestries. A large teapot sits on an open log fire, a man smokes a hookah, while other men drink tea from glasses. On a bench at the far end a man sits playing an oud, a stringed instrument shaped like a pear. These lute like instruments are centuries old, as is the scene before me. The man is singing soulful melodic Bedouin songs. I am mesmerised.

After the buffet I go back in again, but now there are many other visitors chatting and the music has changed to a western style. The mystical atmosphere has gone – for me at least. For a while I watch people dancing in a circle while I sip tea, but I soon wander off outside to look at the stars.

Madaba

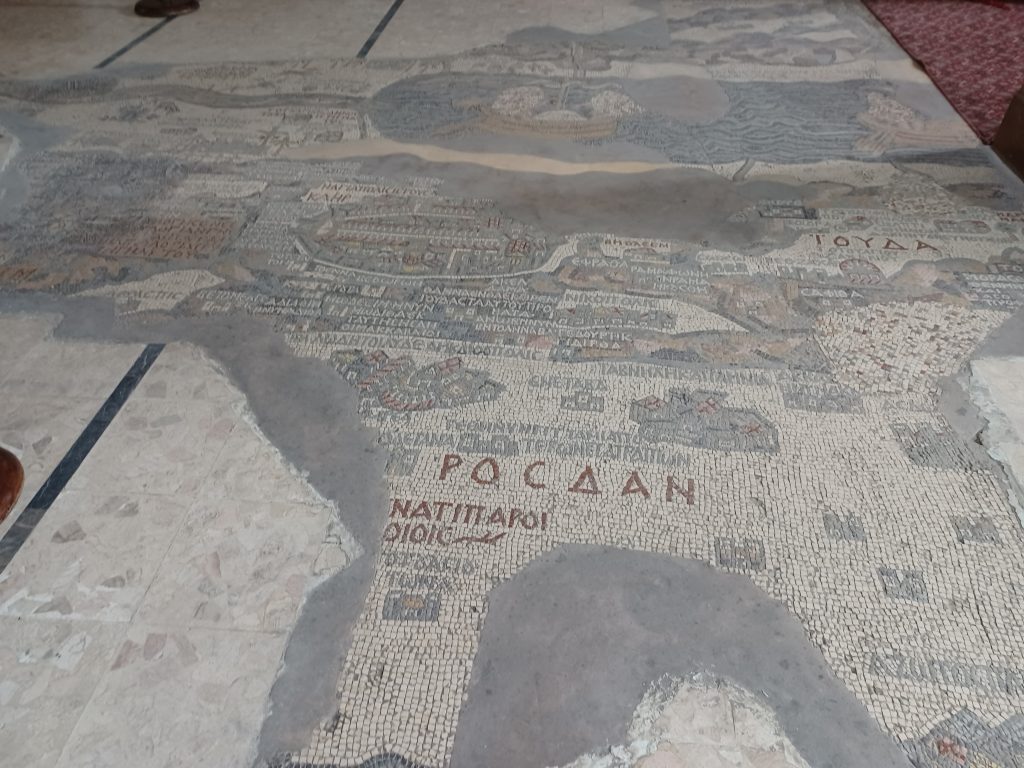

The way continues north on the Desert Highway to our next destination: Madaba. A busy market town in the drizzly distance. We head straight for the Greek orthodox church of St George, a smallish stone church with three arched doorways and a belfry on top. This is where a mosaic map depicting the major Biblical sites was uncovered on the floor in 1884. The oldest map of the area in existence, it dates from 560 BC. The pale pinkish and cream paving stones in front of the church are wet and gleaming as we walk across to the west door and enter.

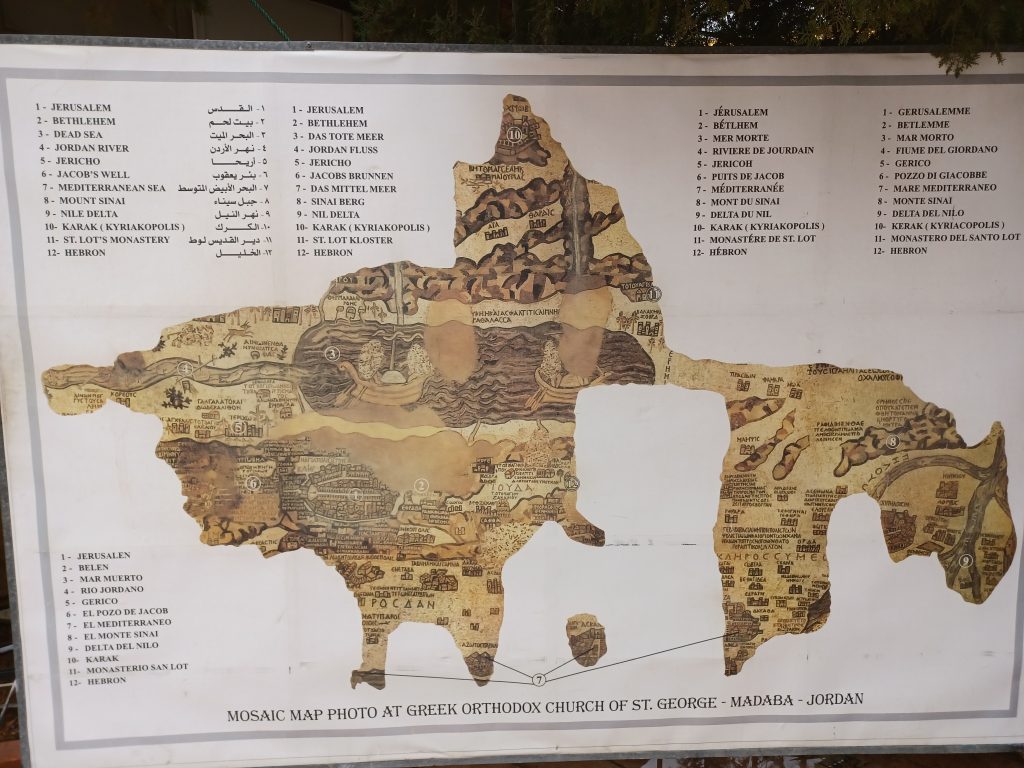

The building faces east west as do all churches. The map is in front of the altar and is oriented in the same way, i.e. east is shown where north usually is ‒ at the top. Although many of the mosaic pieces are missing, one can make out Jerusalem with its city wall, the Dead Sea with boats on it, the River Jordan with fish in it, the Nile delta and Mount Sinai, all with place names, which are difficult to read unless you read Greek. Outside is a large placard showing a copy of the map with a key to its place names in several languages including English. Many interested travellers and me study it earnestly.

Mount Nebo

From Madaba we drive uphill to Mount Nebo, an important pilgrimage site for Christians. Moses is said to have been shown the Promised Land from the top of the mountain here. Not very promising today, it has to be said. The clouds are low and the panorama obscured. There should be a splendid view over the Biblical sites of Jerusalem, Jericho and the Jordan valley. I assume Moses had a decent view when he was here. All I can see is some rocky terrain descending into the valley below and a few signposts pointing out where these sites are. There is, however, an interesting bronze monument on the viewing platform, designed by an Italian sculptor, in the shape of a cross with a serpent entwined round the top of it. It reads: “Just as Moses Lifted up the Serpent in the Desert, the Son of Man Must be Lifted up, So that Everyone Who Believes in Him May Have Eternal Life” (John 3: 14-15).

Adjacent is a newish Memorial Church of Moses, built on top of the original fourth century stone foundations. I enter. Incredible mosaics on the floor. One of them depicts hunting scenes with men on horseback with spears, lions, an ostrich, a zebra, a kind of humped giraffe, flowers, and trees, which look rather like those pomegranate tree mosaics made by the present day local artisans.

Time to head back to the car now and plunge through the clouds to resume our journey. To the Dead Sea. Located in the Jordan rift valley.

The Dead Sea

I visited Israel in my youth and saw the Dead Sea in the distance from that side but have never seen it close up. The Dead sea is the lowest lake in the world at 408 metres below sea level. I suppose this is why it is on every tourist itinerary (Lake Titicaca in Peru is the highest lake in the world (note to self: I have not been there yet)). To get to it, we leave Mount Nebo, at 700 metres above sea level, to descend a long winding road towards the Dead Sea Highway. It is quite steep in places and green with grasses, scrubby bushes and cacti. A goat gambols across some rocks. Funny things happen to my ears. As we descend the temperature gradually gets warmer. This seems contrary to what one would expect in that heat rises. Anyway, for once I am glad it is winter. We have been booked into a Dead Sea hotel restaurant for lunch, followed by a dip in the Dead Sea waters, should we so desire. I have no desire, but am very happy to watch my fellow passengers do so. Anyway, my ears are still blocked.

After a sizeable lunch, we exit the restaurant and descend a gentle zig-zag path, bordered by palm trees and low bushes. It is spitting with rain. “Are you going in?” asks a lady in beachwear as we approach fully clad. “You cannot come to the Dead Sea without bathing in it.” I find a wooden sunbed, just vacated, and laze upon it watching my friends, now in their costumes, and others frolicking on the messy beach. At the water’s edge is a salty sludgy mixture covered with footprints. Tubs of mud are arranged there. They smear themselves with the stuff. I am sure it will do them a lot of good. I am told that it has been used for healing purposes since the time of King Herod. They seem to enjoy it. It is not really possible to swim in the thick water, but they can float and splash about. Anyway, there is a red flag on the beach and a sign next to it warning people: ‘No swimming’ and ‘No diving’.

I gaze out over the placid grey water at the low brown hills of the West Bank beyond. Beneath the lowering clouds lies Jerusalem somewhere over there. The Dead Sea itself is devoid of life because it is, literally, dead. No birds, as they have nothing to eat as there are no fish, and no fish because there are no living creatures for them to eat either. Not much use for anything although, apparently, the ancients found bitumen in it, which they could trade with the Egyptians, who used it in the mummification process.

I wander back up the path. Near the hotel swimming pool I spot a Palestinian sunbird extracting nectar from a flower with its down-curved bill. It has an alluring blue iridescent colour. Pause awhile and watch. Our driver, smoking a cigarette and drinking tea on the terrace, tells me that the Dead Sea is drying up because the River Jordan does not have so much water in it as in times past. “The farmers, you see, both from Israel and Jordan, have taken the water for crops. So there is less water running into the sea.”

Desert forts

Back in Amman for a night and I take leave of my fellow travellers, who are heading off elsewhere on the morrow. I have arranged to be taken towards Azraq in the east of Jordan to visit some of the many Umayyad hunting lodges/forts/inns/caravanserai – call them what you will ‒ en route and the fort at Azraq where T.E. Lawrence spent a winter. The itinerary is solely down to me. Hoorah. There are a couple of these ruined desert ‘castles’ on the way to Azraq that I want to see: Qasr Al-Harrana and Qasayr Amra, which date from the time of early Islam (around 650 – 750 AD).

I take the Eastern Desert Highway, now a road less travelled, with a different driver, specially assigned to me for this trip. Once out of Amman, the road streaks out over a flat featureless plain of volcanic basalt rock, quite different to the soft red sandstones of Wadi Rum and Petra. One or two dust devils swirl about, a scene of desolation. By the side of the road Qasr Al-Harrana rises from the plain, a substantial yellowish brown stone square structure. An information board from the Department of Antiquities throws doubt on its original function but it could have been an early inn. I venture inside to the central courtyard, which has many rooms off it on each side all with arches over the doorways and vaulted ceilings. I clamber up the uneven steps to the next floor where the arrangement is similar. Massive are the walls. These prevent the wind slicing through the one or two travellers visiting on this winter’s day and, in the hot summer months, provide a cool refuge. While once an oasis for travellers, it is scarcely enticing today.

The road continues its bleak way into the long wedge shaped eastern desert, with Syria to the north, Saudi Arabia to the south and east and Iraq to the north-east. “Your Winston Churchill drew Jordan’s borders”, my driver tells me. Eh? Apparently Churchill boasted that he drew the zig-zag border between Jordan and Saudi Arabia ‘with a stroke of a pen’ creating the British mandate of Transjordan – east of the river Jordan (west of the river was Palestine) – after a liquid lunch in Cairo in 1921. The border is also known as ‘Winston’s hiccup’. I wonder how the driver learned this ‘fact’ as the story is really a myth. The border was not drafted until 1922, when the Emir Abdullah met with the British Colonial Office, and only concluded in 1925, when Winston was no longer the British Colonial Secretary. Anyway, the ‘new’ country was given access to the Red Sea with a short stretch of Red Sea coast around Aqaba. My driver tells me that Jordan exchanged some territory with Saudi Arabia for a further eighteen kilometres of the Red Sea coast in 1965. “That was a good deal”, he says.

And so to Qasayr Amra, now a UNESCO world heritage site, built in the 8th century as a hunting pavilion for members of the Umayyad family. Again, a building of yellowish brown stone, with a dome at one side, greets me as I head towards it down the path from the visitor centre, which is closed. It seems quite small from the road and is well camouflaged in the sandy gravelly landscape. The scenery was different back in Umayyad times, green enough to sustain game, such as the Arabian oryx, and full of trees, such as described in the the first verse of the poem, ‘Kubla Kahn’ by Samuel Taylor Coleridge:

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round;

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree;

And here were forests ancient as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery…

Today’s nondescript exterior belies what lies within this hunting pavilion. Colourful murals are on every wall depicting scenes you would not normally associate with Muslim culture. A seductive bare breasted lady stands in a bath of turquoise water with her skirt hitched up. A pendant drops between her breasts. To her right are wrestlers and above them all a pack of hunting dogs chases some kind of gazelle into nets. Men are shown spearing animals on another wall, while on another a man is playing an oud (like the one the Bedouin man was playing at the camp in Wadi Rum). On the ceiling are four sided shapes inside of which are animals, people and bunches of red grapes. Some depict camels and men carrying out various tasks, while the yellowish ceiling of the dome appears to depict the signs of the zodiac.

Shame the visitor centre is closed. However, a large Bedouin tent near the exit is open for visitors. There is a glowing fire burning inside. A welcoming refuge. One side of the tent is of black woven wool with horizontal white stripes, while the other side is red with black stripes. A large Jordanian flag occupies the whole of the far end. My driver is in there chatting to the owner, a long haired Bedouin dressed in a long black robe with a blue denim jacket over it. Another man sits on a low seat and stokes the fire. The atmosphere is smoky and warm. A glass of tea with cinnamon slips into my hands. Just right. I sit sipping it in front of the fire. I buy some tea leaves and spices along with a mobile decoration of coloured camels, which I spot hanging from the ceiling near the fire. It smells of smoke. “The Bedouin are grateful when tourists buy their crafts,” says my driver.

Azraq

And so to Azraq. I had two motives for visiting: firstly as there is an area of once extensive wetlands here, which I had read was a haven for winter birds, and secondly because of its connection with the Arab revolt and Lawrence.

I stay at Azraq Lodge, once a British military hospital. An old green short wheel base Land Rover with a canvas roof is squatting in the black sand by the entrance. No number plate.

In the entrance hall are some fading photographs lining the walls. The accommodation is fairly basic but my window looks out over the town with the much dwindled area of trees in the oasis in the distance. The food, served in the old canteen, is substantial and delectable.

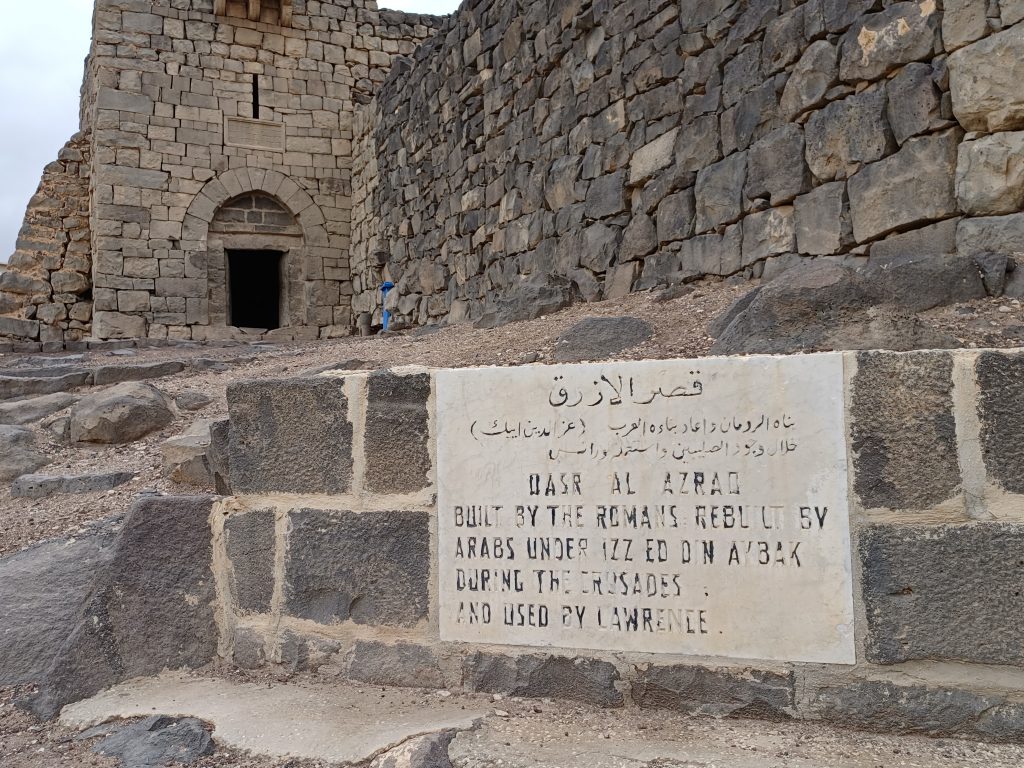

Thus nourished, I wend my way to Azraq Fort. The sign that greets visitors at the entrance says that it was built by the Romans, rebuilt by the Arabs during the crusades ‘and used by Lawrence’. It is a large crumbling ruin of black stone. A few areas have a roof still standing, one of which was supposed to be Lawrence’s room where he sojourned during the Arab Revolt in the winter of 1917-1918. The other buildings have no rooves at all. Somewhat uncomfortable and cold, I would say, although one can see black soot on the ceilings in some places where the residents lit fires.

Maybe the redeeming feature was the nearby oasis with its wildlife. However, full of anticipation and armed with my binoculars, there is not a bird to be seen when I arrive there. The one kilometre or so trail lacks all life except for one or two humans. Vexed. I wonder why though as the wetlands are supposed to be used by birds during their winter migration. Maybe the water levels are too low. This oasis was once a source of water, but the water has been steadily removed over the years to provide for the population of Amman so that now there is only about 10% of it left – and most of that water has been pumped back in. In 1991 it almost dried up completely.

On the way back to the city, my driver tells me about the problems that hospitable Jordan faces. Bordered as it is by war-torn Syria to the north, in the west by Israel, north-east by Iraq and the east and south-east by Saudi Arabia, it is situated in an area of political and religious tensions and hosts thousands of refugees in several camps, most recently from Syria. Tourists are needed, he believes, to fill the coffers. Add to that is the fact that Jordan is a small country, it is mostly desert and situated on a fault line, where two tectonic plates meet ‒ the Arabian and African plates. The fault line runs along the Jordan valley from the Sea of Galilee, through the Dead Sea and onward to the Gulf of Aqaba. Thus the area is subject to seismic activity, as has been the case through the centuries, one of the probable causes of the decline of the ancient cities of Jerash and Petra.

I am in bed. It is my last night and I feel the tremors of an earthquake in my hotel. Slightly rattled. I get up and dress and lie down again, prepared to evacuate quickly. Several more tremors follow. It was only much later that I discovered I was on the fringes of the major 7.8 magnitude earthquake which struck south east Turkey in February 2023. A somewhat dramatic end to my visit to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

Leave a Reply