A gentleman I know owns a boat share and invites me to crew for him. The boat, made in Holland, registered in UK and based in France, is 38 feet long, of white painted steel with a navy blue streak round the topsides, and varnished wood with blue cushions below decks. And she is quite lovely.

Messing about on boats is, as an American friend of mine had once observed, ‘my happy place.’ I did much boating in my youth, both on oceans and waterways, and owned various vessels at various times. And one of my retirement plans was to do some more boating. Every now and then the thought of buying a boat again cropped up to disturb my sleep. What should I buy? A beautiful wooden boat full of character? Perhaps not. Such vessels require a lot of maintenance. Fibre glass boat? OK but they are not very pretty. Anyway, I pondered, can I afford to own my own boat? Is it sensible? Am I likely to spend enough time aboard to make the expense worthwhile? For it is costly to run a boat. For example, mooring fees in UK are generally high wherever you are – coast or inland waterway. But here I am now being offered to crew for four weeks or so every Summer in la belle France. What’s not to like!

Savoyeux to Auxonne

Our cruising area is within the south-east part of the Burgundy region, famed for its architecture, in particular the glazed coloured roof tiles seen atop many churches and public buildings. Famous also for its wines. This season’s voyage begins in the Port de Plaisance at Savoyeux, a largish marina just north of Gray, with several pontoons packed with boats.

So here we are, floating along the Saône, a wide, deep river, with not too many locks ‒ most of which are automatic anyway ‒ along its length, and which has been canalised in several sections. We are actually on the ‘Petite Saône’, the river’s upper reaches, here and the plan is to head south and pop up and down a few of the waterways either side, should the inclination take us. Navigation along the river with our French waterways guide is straightforward but, should reassurance be required, there are piquet marks every kilometre. These are big boards along the river bank with numbers on them corresponding to those in the guide.

The sun is shining, the skipper, wheel in hand, is beaming under his hat, and self is checking that the mooring ropes are coiled and ready to throw around a bollard when we reach the first lock. We descend through it effortlessly. The canal meets the river at the foot of the lock. Cattle have gathered to drink below the trees on the river bank and a couple of cattle egrets shuffle about in the low grass behind them. We scare a kingfisher that shoots off flashing turquoise and a mallard paddles into the lilies. Smells of cut grass waft across the aft deck. Enveloped in nature.

We stop at the largish town of Gray for the night. An old stone bridge spans the river, and the Basilica of Notre-Dame de Gray sits atop the hill, its bell tower with its three grey coloured cupolas on top of each other poking above the treetops. We tie up alongside the river wall and stretch our electricity cable across the grassy bank to the power point. Gray is spread out along both banks of the river and is a convenient place with a good supermarket. One of the less glamourous aspects of cruising is the need to stock up every now and then of course. But the boat’s fridge is of sufficient size, and there is room below the galley floor to store wine and other essentials. A table and chairs grace the aft deck over which a bimini provides shelter. Time for refreshment.

Not far south of Gray the next morning, a small settlement appears on the left bank with its stone buildings and bell shaped tower nestling in the trees behind an expanse of grass. A lone boat is moored on the gently rippling river alongside a longish wall near a weeping willow tree. Unspoilt France. There are many such old villages, buildings with sometimes crumbling facades and faded paintwork along the river bank. Few high rise apartment blocks or unsightly estates. Sweeping green landscapes and huge skies. We plan to moor here on the way back. The village is called Mantoche.

Auxonne

But our plan is to reach Auxonne today and, after some more gentle cruising, we turn into the lovely marina of Port Royal, birds chirping all over the place. A boat owner close by hops off his vessel, cigarette in mouth, to help us moor. “Merci beaucoup”. The marina manager appears to take another line. “Bonjour Monsieur-Dame et bienvenue”. He is full of bonhomie and information. He relieves us of a few euros for our night’s stay and points to his office to which we should go should we require any assistance. Sparrows are twittering in the bushes opposite the mooring and we see some adult coypus and their young swimming about in a large pool as we amble along the pathway around the marina. Coypus are large semi aquatic rodents with long thin roundish tails. An adult swims in our direction, its nose and white whiskers held above the water. They used to be hunted for their fur apparently and were originally native to South America. Quite why there are some here I know not.

Auxonne is a pretty town with another church of Notre-Dame, a castle, and Hotel de Ville (town hall) in front of which stands a statue of Napoleon. Napoleon was a mere 18 years old when he came here to the Auxonne garrison in 1788 and some of the then Lieutenant Bonaparte’s belongings are housed in the castle museum. No doubt he would have spent time in the church too. We go in. I like churches. It is Gothic and has a large nave with tall arcades with capitals and vaulted ceilings. Very like many of our English cathedrals and churches. Early English stone masons of the time took ideas from the French before developing their own distinct English style. The clergy’s seats have miserichords (mercy seats) underneath them under which are carved fantastical shapes of lion’s heads and monsters. These were designed for tired clergymen to lean against when they were standing up for long periods.

We are about to leave when one of the military from the garrison, dressed in uniform, begins to play the organ. It is his daily practice time. The music echoes round the old church. We sit on chairs and linger for some time soaking up this unexpected bit of spiritual stimulation before exiting into the bright sunlight.

An alluring restaurant appears on a side street with tables and chairs on the cobbles. A waiter slides out of the shade. Said waiter turns out to be the helpful fellow who took our line as we entered the marina. He still has a cigarette in his mouth. I suppose it is a different one. Steak and frites are ordered plus glass or two of Côtes du Rhône for our lunchtime snack. Temperature about 28 degrees C. Sunshade provided. Long lunch. Back to the boat now to plan next day’s cruise.

Locks and the Rhône-Rhine canal

Continuing down the Saône for about fifteen kilometres from Auxonne, the skipper steers to port, about to enter the canal which connects the Rhône/Saône to the River Rhine but we are greeted with a red light upon arrival. A large sign, ‘Canal du Rhône au Rhin’, sits above the entrance to a large lock. It is lunch time and, as this is a manned lock, we have to wait until the lockkeeper has finished his lunch. Actually, it is some minutes before the lock is supposed to be closed for lunch but that does not worry the French lockkeeper. He is master of his own little empire here. We moor up and settle down to make lunch too. Freshly baked baguettes and French cheese along with a glass or two of the local red. Eventually, we see said lockkeeper enter his lofty perch above the entrance, the light turns green and we begin our passage through the lock – going up.

It is always more tricky going up through a lock than down it. This is a deep one. Damp walls hem us in as we enter at the bottom of the lock. The gates are shut, water is let in through the upper gates and causes quite a maelstrom as it rushes in and the water level steadily rises. I have attached the vessel amidships to a bollard in the wall, but we need another rope on the stern to steady her as she is swinging about a bit. The skipper throws a rope round another bollard. As we rise, I take the rope off the bollard to move it up the sides of the lock wall onto the next one above. Some tense moments. Eventually the vessel surfaces at the top of the lock, I breathe a sigh of relief, the gates open and we venture forth ‒ several meters higher than before – to explore new waters.

Before we reach our next port of call, Dole, seven more automatic locks await us. The means of operating the locks are various. On this canal, a long plastic tube hangs over the waterway, about a hundred metres before the lock. I stand poised on the foredeck, the skipper heads for the tube, I grab hold of it and give it a firm twist. A light starts flashing near the lock gate to let us know that the twist has done its job. On other canals, such as the Rhine-Marne, the lockkeeper at the first lock gives the crew a remote control with which to aim at a panel on the river bank before the lock, which sets the process in motion. Other locks, such as on the Canal du Nivernais, are manned during the boating season, but boat crews often disembark to help the lockkeepers as it takes a longish while to manually close one set of gates, lower the paddles, open the other set, enter, close the gates, raise the paddles and so forth. Manned locks are subject to French opening times and lunch times ‒ as has been earlier mentioned. Time it wrongly and one may be waiting at a lock gate for a couple of hours in the lunchtime heat. This can be irksome, impacting the time of arrival at one’s final destination or even foil one’s plans to arrive at said destination at all.

One of the locks before Dole has a nasty little cross current in front of it, emanating from a small stream. “I don’t like the look of that”, says the skipper. As we approach, the current takes the boat and shoves it to one side. Not what one wants when one is trying to head towards the centre of the lock. It happened rather quickly and we biff the lock side. Skipper slightly rattled. Fortunately, the vessel is strewn about with fenders, which do their job.

Dole

We eventually arrive at the pretty quayside in Dole, where an area of grass sits neatly behind the moorings and a few little bridges cross a stream. A huge church rises up behind. There has been a lot of lock work to reach this haven, the crew is flagging, it is hot, and we are thirsty. We tilt the bimini a bit to provide shade from the low slanting rays and enjoy a long cool drink before disembarking to explore the town. Louis Pasteur, he who developed the process of pasteurisation, was born here in 1822. We spot a bust of him in a side street and wander down the road named after him, the Rue Louis Pasteur.

A festival is being held in town right now. A band of men in hunting dress ‒ dark frock coats with scarlet waistcoats with golden braid and buttons, long boots and riding hats – are playing their hunting horns in front of the church. We continue our stroll by narrow waterways with lilies, bicycles by railings, tall stone buildings with shutters, ivy covered arches, an old tannerie, cobbled ancient streets and flower covered cafés. One old house has a fresco on it depicting a balcony with people and a clergyman at a window. In front of the house is a green rocking horse on a spring upon which a grinning tourist rocks herself back and forth.

Warm is the evening and we watch the slow moon rising above the water. A magic mooring. We tarry in Dole for a couple of days before heading back down the canal. Locking in and out is much easier now because we are descending through the locks. As we enter one I throw a line around the bollard on the quay. As water empties from the lock, I slowly let out the rope as we sink softly between its walls. Blissfully done.

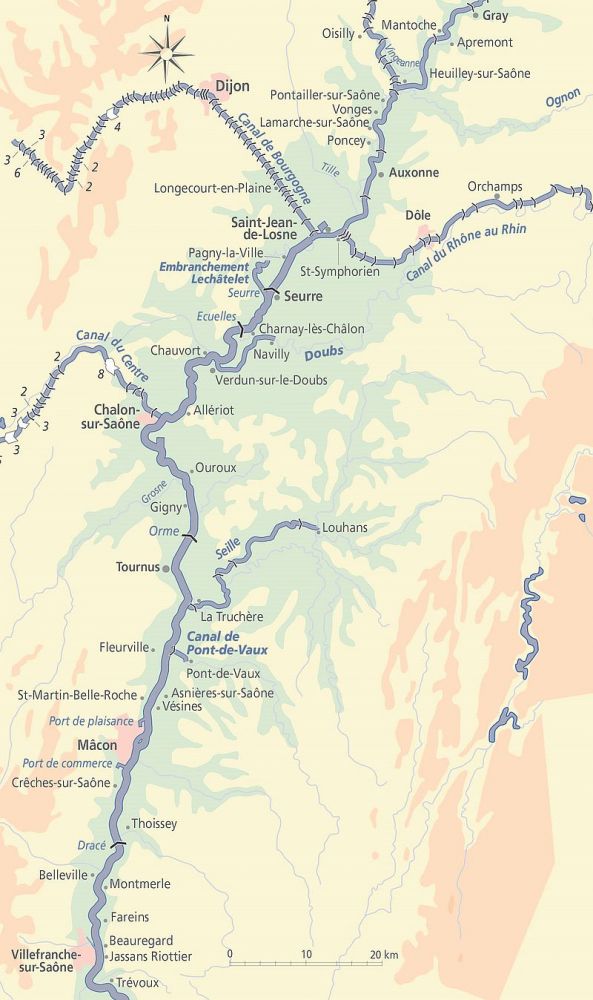

Saint-Jean-de-Losne

Back on the Saône river again and we are bound for Saint-Jean-de-Losne, a large centre for inland navigation. It is here where the Burgundy, Saône, and the Rhone-Rhine waterways meet. These are just a few of the many waterways in France. The French, incidentally, built their canals before the British did. The Duke of Bridgewater in the 1750s had seen the Canal du Midi in the south of France, which was built between 1662 and 1681, and was impressed. On that basis, he employed James Brindley, an English engineer, to build a canal for him to transport coal from his coal mines to Manchester. Thus was the first canal in England built eighty years after the Canal du Midi. English canals are different to the French ones. Most of them are quite narrow, thus only narrow boats with a 6 foot 10 inches beam can navigate them. Some canals, such as the Grand Union Canal, are wider and can take wide beam boats and cruisers. The French waterways, however, are mostly wide and take boats of different shapes and sizes. But I digress.

Saint-Jean-de-Losne used to be full of wooden barges, ‘peniches’ among others, which would transport raw materials such as coal and wheat around the network. These old wooden barges are obsolete although there is one here, which is being renovated, and others which have been converted as liveaboard boats. There is an interesting museum (Musée de la Batellerie) about the old barging life in town, which we visit. Commercial traffic today consists of huge steel barges operating down the Saône to join the River Rhone and thence to the Mediterranean.

The port of Saint-Jean is not perhaps the prettiest of places to moor but one can find all facilities here and it is very handy for purchase of chandlery and for any maintenance issues. There is a boat brokerage here too. It seems to be a good place to sell vessels and we see many with ‘a vendre’ signs on them tied up together on both sides of a long pontoon. There is also a hire boat company, as in many other places on the waterways. These companies offer boats for hire at various levels of expense. The boats are mostly what the skipper, rather disparagingly, calls “plastic fantastics” but they serve the purpose of permitting relative novices at boating to explore the waterways and have extra strong rubbing strakes (boat bumpers running round the topsides) and good manoeuvrability. I may have forgotten to mention it but owners of boats in France have to have an International Certificate of Competence and pass a test, run in UK at least, by the Royal Yachting Association (RYA). The point being that the French view it as preferable that boat owners know something about boat handling, although apparently the same does not apply to boats hirers.

Saint-Jean-de-Losne to Verdun-sur-le-Doubs

There follows a short voyage to Verdun-sur-le-Doubs. As we float past a little swimming area south of Saint-Jean-de-Losne, three young Frenchmen bare their bums at us. Somewhat discourteous I feel. Is it because we are flying the red ensign I wonder? For the uninitiated, etiquette demands that vessels fly the flag of their country of registration off the stern while, on the mast, one flies the courtesy flag of the host country. Our British registered boat thus flies the red ensign (or ‘red duster’), which has a red background with the Union Jack in the upper left canton, plus the French courtesy flag. Right now, we are also flying the flag of Ukraine opposite the French flag, as a gesture of support for that country. The red ensign, incidentally, was established by Queen Anne in 1707 (just so you know). I don’t know why the maritime flag is different from our national flag but, anyway, identification should not be difficult. These Frenchmen clearly have no problem. We could take umbrage but choose to ignore their bare bums.

We arrive in Verdun-sur-le-Doubs mid-afternoon. The Capitainerie, where one checks in one’s vessel and pays the mooring fees, stands high above the moorings on a massive wall, part of the old fortifications of the town. The female Port Captain descends to help with the ropes. “Merci beaucoup”! The clouds threaten rain, which begins just after we have moored. There is a bar in the Capitainerie or the Capitainerie is in a bar, one or the other. The Port Captain seems to be the owner of the bar in fact. So, we flop down at a table and a short time later are happily quaffing drinks while overlooking our boat and watching the entertainment as other boats arrive to reverse into ever less space at the pontoon – in the rain.

There is nothing quite so enjoyable as observing other people’s boat handling, especially when one is already moored up and relaxing with a drink. It is so easy to mock the skipper, usually a male, making a mess of it. “Whoops, look out”, as he bumps the topsides of the boat alongside. We discuss how it could or should have been done better. We hope to dine this evening in a fine restaurant near the Capitainerie but it is Sunday and it is closed. “Ah, maybe Monday instead then”, say I. But it is closed then too, not open until Tuesday. The French, it seems, do not believe in opening for passing trade during their ‘weekends’, even at the height of the season. We dine on board instead. We sit below, the candles are lit; French accordion music plays; the skipper cooks a delicious meal. Who cares about a French restaurant anyway.

It was one of those magical misty mornings, when I was not up with the lark. I heard the thirteenth century church clock of St Jean chiming over the boats on the moorings announcing the time. At my age, however, I am taking things easy. I don’t have to explore every creek, visit every museum, be restless and anxious to experience all (at least, that is what I tell myself). Anyway, the fish were still splashing at 10 o’clock. This is a good place for angling I have heard, because of the confluence of three rivers. We missed an early morning rain shower, which a German boat must have received in abundance as it left much earlier, while we were still supping the first cuppa in the warmth and cosiness of the saloon. There was a hail storm the other day, hail stones the size of pennies. Hope they didn’t get caught in anything like that. Especially on approach to a lock or the final mooring for the night, like those boats yesterday. I have experienced that. I have been soaked through when the rain was so torrential that the water was unable to drain quickly enough through the slits between the boards of the jetty. Something most assuredly to be missed.

Verdun-sur-le Doubs to Chalon-sur-Saône

And so continues the gentle motor down river. Wooded banks are interspersed with open green stretches with somnolent cattle, mostly the whitish Charolais breed. A stately heron glides across the water ahead of us and makes a perfect landing on a branch in the thick wooded river bank edge. Every few hundred metres a heron can be observed, poised, tall and straight, focussing its gaze in the river below. Some of the herons are black crowned night herons, which I have not seen before. They have black heads and backs and appear more hunched up than the more common grey herons. I scan the banks with my binoculars hoping to add to my bird list. 50 and counting. Destination: Chalon-sur-Saône.

This is the last upriver port which the large river cruisers can reach. We see two of them, 110 meters long, the longest length possible in the locks on this section of the Saône. They are moored along a quayside. One is registered in Valletta, Malta and the other in Basel, Switzerland’s port of entry on the Rhine. I note that one of them is called ‘William Shakespeare’. This type of cruising is perhaps a good alternative to owning or hiring a vessel, if one wants a more luxury experience. But there is nothing much better, in my opinion, than conning one’s own boat, mooring up where one likes, staying as long as one likes. Following the chart and the buoys, we turn the boat to port around the Isle of St Laurent and enter the pretty port du plaisance of Chalon-sur-Saône.

I love entering new ports. One gets an entirely different view of a place from the water. A tall brick tower, the Tour de Doyenne, is on the edge of the little island with a flower bed below. We throttle back as we enter the marina. A young man in yellow shorts is already on the pontoon to take our lines and help us moor up as we approach. It is sunny. Boat tied up and secure, the skipper goes below and pours drinks. He conveys them onto the after deck, which is shaded by the large bimini. “You are wonderful”, I say. “This is undeniably true”, he replies.

Characterful old neighbourhoods grace the town of Chalon-sur-Saône with squares, dotted with cafés, churches, town hall and gardens. The cathedral of St Vincent is memorable with its twin towers; and half-timbered old houses from the 15th and 16th centuries sit around the square. It is rather warm. Thus we also sit in this square and order drinks. They arrive in long glasses with swizzle sticks. There is a fountain here with a huge stone ball in it down which cascades water. The water is sometimes pink apparently (it isn’t today), which symbolises the flowing burgundy wine from the region. The town is surrounded by vineyards and is situated on Burgundy’s Route des Grand Vins. Wine lovers rejoice!

Chalon-sur-Saône to Tournus

About 30 kilometres south of Chalon is Tournus. This is probably the furthest south that we will venture during this trip. We do not rise early. And we like to linger over breakfast. The skipper likes coffee, I prefer tea, but we concur on croissants and yoghurts. Then some action. Chart is placed next to the upper helm, the binoculars follow. All set, normal checks, engine on, and we edge out of our mooring spot and motor gently out onto the river. The river shimmers in the sunlight. We wave to a passing boat crew flying the Swiss flag and settle down at an easy five knots to enjoy the wind on our faces and the long sweeping reach of the river.

Tournus looks a bit run-down as we approach, although two imposing towers rise beyond the waterfront. There is one pontoon for pleasure boats and further down is the quayside for the large river cruisers. We squeeze in on the end of the pontoon, where a sign in French warns us we should not moor. But there is nowhere else so we tie up anyway. Engine off, various bits of crockery stowed below, we shut the hatch and go ashore, greeting boat owners of various nationalities on the way. “Bonjour”, “guten tag”, “good afternoon”.

We wander towards the towers of the Abbey of Saint Philibert, which we observed as we came down river. Opposite the Abbey is a restaurant/bar with foliage climbing up its grey stone walls. Cyclists in shorts and baseball caps leave their bikes alongside, a woman in a wheelchair is pushed by, and tourists take photos of this old monastic centre, one of the oldest in France. It started as an oratory constructed over the sixth century tomb of Saint Valerien, over which a second monastery was built, where the monks of Saint Philibert settled in the ninth century. As happened in England (for example, Lichfield Cathedral’s St Chad and Durham Cathedral’s St Cuthbert), the relics of the saints attracted many pilgrims in medieval times, which contributed to Tournus’ growth. Saint Philibert’s is a splendid Romanesque edifice with round arches in the nave; chapels and crypt. It smells musty and ancient inside. Neatly trimmed green hedges fill the cloister gardens. A place of prayer and contemplation.

I like Tournus. A mix of old and new, the orderly and the dishevelled, cobbled streets and old lamps in alleyways and misshapen rooves. An armed gendarme is on the pontoon as we return to the boat. He points to the sign telling us we should not moor on the inner side of the pontoon, which we had ignored, so we pretend not to understand what is written. After one or two words of disapproval and a gallic shrug he collects from us the night’s mooring fee. “Merci beaucoup, au revoir”.

River Seille

A passing boat crew had waxed lyrical about a place named Louhans on the River Seille. “You must go up there. It is gorgeous”, we are told. Thus, despite not intending to head further south, we find ourselves wending our way up this rather shallow river, not far from Tournus, where the locks are manual. These prove fairly arduous after the automatic locks we have enjoyed everywhere else. “Whose idea was this?” ask I of the skipper, as I open lock gate after lock gate. He hops off to help out. Beats going to the gym. There are several pretty little places along the banks of the Seille including a picturesque old water mill on a now placid inlet of the river covered with water lilies. Two men are fishing there from a red dinghy. There are some great white egrets flying about too and, as we round a bend, we see a group of Charolais cattle having a dip on the water’s edge.

Louhans itself is indeed lovely, with its old stone buildings and arcades along the main street, and the towers of the fifteenth century church of St Pierre are resplendent with the traditional ceramic tiles: yellows, blacks, browns and greens, of the Burgundy region. On a more sombre note, there are also some plaques and monuments commemorating members of the French Resistance in WWII who were killed here.

Time now to head north. We retrace our route past Chalon and the entrance to St-Jean-de-Losne. The Saône is broad here and many barges are moored along the banks. Fish are jumping and we pass clearings in the woodland where French fishermen have erected tents. Their rods extend out over the river. Other pleasure boats are tied up to trees and some of their crews are swimming. We throttle back so as to create less wake. They wave in acknowledgement. Well, some of them do.

Ray-sur-Saône

The last place that the skipper is keen to visit is Ray-sur-Saône, a short hop north of our home port. This is because it has a restaurant, well known on the boating grapevine, called Chez Yvette, Yvette’s place. We tie up in the creek and make a beeline toward this haven. The restaurant has no menu. One receives whatever is being prepared that day and has a lunchtime feast. Yvette bustles about and fills up the plates, glasses clatter, and the significant number of locals tuck in, as do we. Terrific ambience and fine French cooking.

Back aboard for an afternoon’s rest and digestion, I behold birds on the grass. Chestnut coloured with black and white barring on the wings and crests. They are hoopoes – three of them – poking their long curved beaks into the grass to extract insects. Even the skipper, not generally enthusiastic about my pastime, pauses over his wine glass to watch them. Meanwhile, a fisherman floats by on what can only be described as an inflatable seat. Facing backwards, his legs dangling in the water alongside a large net, he is oblivious to our presence as he baits a hook for his line. I wonder how he steers – with his feet perhaps. The hoopoes have flown into the large deciduous trees on the opposite side of the creek and I watch them through my binoculars. A couple of swans glide by and we laze away our last long tranquil afternoon.

I love boating, and I love France and, of course, France is in England’s back yard and is relatively easy to get to. In fact huge chunks of France used to be owned by the English but as one Plantagenet King gained vast amounts of territory, for example Henry II, Edward III and his son the Black Prince at Crecy (1346) and Henry V at Agincourt (1415), others then lost it, e.g. John, Henry III and Henry VI. Henry VI, in fact, was the only King ever to be crowned King of France – in 1431 ‒ as well as King of England, but he managed to lose most of it. By 1453 the English owned only Calais. And a hundred years or so later that was gone too. Shame really.

Leave a Reply