Covid 19 it was that thwarted my forays to the Southern Caucasus in 2020. I was, at the time, living east of the Caspian Sea and this region lies to the west of the Caspian Sea. It would have been a fairly quick flit across therefore but, frustratingly, postponed. The area is a bit off the beaten tourist track, a notable attraction. And there are many dramatic landscapes to be experienced, from awe inspiring mountains with majestic monasteries perched atop, burbling brooks and stygian forests. Five years later and I finally get here via a much lengthier route from the UK.

The Southern Caucasus is sandwiched between the Black Sea to the west and the Caspian Sea to the east, and between Europe and Asia. There doesn’t seem to be much agreement about exactly which continent the region should be placed in. Some organisations place it in Asia, others have determined that it part of Europe. Some place the western part in Europe and the eastern in Asia. Yet others locate it in the Middle East. It comprises the three ex-Soviet republics of Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia, the Greater Caucasus mountains providing a natural northern border with Russia; and the Lesser Caucasus a southern border with Iran and Turkey. Between the two ranges lies a large area of fertile lowlands, where fruit trees grow in abundance, and vines and vegetables.

I have booked a tour with a reputable company. It includes flights. So I really have nothing to do at all except hand over the cash, put my feet up and await the departure date.

Azerbaijan

Land after midnight in the land of fire. So-called due to Azerbaijan’s abundant supplies of natural gas and oil, and the link to the sacred fires of their ancient Zoroastrian ancestors. Meeting us at Heydar Aliyev Airport, named after the current President’s late father, is our guide for the next few days. Huddled with a few others, I dawdle in a sort of daze whilst said guide attempts to ascertain the whereabouts of a couple of the participants on the tour, who appear to have missed the flight. Finally, a decision is taken and we exit the airport without them. Sometime later, we pull up at our hotel in the capital, Baku, at 03:30. Instructions are to meet in the hotel foyer at 11:00. Time enough to rest up, perhaps.

The tour transport, it transpires, is in the form of a big red coach. With space aboard for the eventual eighteen group members to have two seats each to themselves. Splendid. Thus, at 11:00, we motor our way to the centre of Baku. The hotel is a bit too far out to hoof it, actually far too far out. I have commented on this fact before (see Spain, Part 1), that tour companies often accommodate largish groups in hotels out of town, purely, one supposes, due to the convenience of parking big red coaches in the precincts. But scarcely accessible on foot to the sites about town. Mustn’t grumble. Nice room.

Baku

Martyrs’ Lane and the Eternal Flame Memorial

At the bottom of stone steps leading to Upland Park, where we alight, flies a large Azerbaijani flag. This flag marks one end of Martyrs’ Lane, which is lined with tombstones made of black marble, upon which lie martyrs’ names and portraits. Jolliest bits of history first on the agenda then. Our guide, a slim, debonair, purposeful sort of chap, and highly articulate, begins his spiel. “Let me tell you that these tombstones commemorate those who died during Black January in 1990”. This was when the Soviets under President Gorbachev sent troops with tanks into Baku. Hoping to crackdown on Azerbaijani nationalism, the troops massacred protesters. After a curfew was implemented, which some knew nothing about, according to our guide, more people were killed in Baku, including women and children. A grim reminder of Soviet reaction to anything that threatens their regime.

At the other end of Martyrs’ Lane, ahead of us, is a memorial housing the eternal flame. The Eternal Flame Memorial also commemorates the victims of the first Nagorno-Karabakh war between Azerbaijan and Armenia between 1988 and 1994.

From the Eternal Flame Memorial there is a glorious view over the Caspian Sea. As we peruse the panorama our guide waxes lyrical about the sights there arrayed. On the right is National Flag Square, with a large platform supporting “the second largest flag pole in the world”, he tells us, “after the one in Cairo, which is the biggest”. “But our flag is the largest in the world”, says he boastfully. Weighing 350 kilograms. Impressive. An explanation of said flag follows: it was designed during Azerbaijan’s two years of independence from 1918 to 1920. Before this, the country had been part of the Russian Empire for 80 years. And after the Soviet invasion in 1920, the flag was “folded and put under the pillow” for a further 71 years. Finally, under Gorbachev’s policy of perestroika and glasnost, the unintended consequence of which was increased nationalism in the Soviet republics, Azerbaijan, along with thirteen other former Soviet republics, withdrew from the USSR in 1991. The flag was then resurrected. The blue colour represents the Turkic identity, the red progress, the green Islam ‒ the religion of the majority of the population.

Next to National Flag Square is Crystal Hall, built to host the Eurovision Song Contest in 2012, and to the left of these is the Baku Eye, a Ferris wheel. Then comes a lotus shaped building housing a shopping mall; and a small boat harbour. And in the distance is a headland full of unlovely Soviet concrete blocks.

These were built under Khrushchev as a reaction to Stalin’s excesses. Further left, reflected in the waters of the Caspian, is a crescent shaped glass building designed for residential purposes, though not yet complete, and myriad other architectural wonders along Baku’s boulevard, including a carpet museum shaped

like a carpet. And in the Caspian Sea can be seen some ships. It is possible to catch a ferry from Baku across the Caspian to Kazakhstan. Thought about doing that crossing once but didn’t. Anyway, it is time now to head back the way whence we have come. We saunter along Martyrs’ Lane with the three iconic Flame Towers, erected in 2012, symbol of modern Baku, providing a stunning backdrop. Then file down the flights of steps towards our red coach.

Baku Old City

Now bound for Baku’s old city, Icherisheher, which has been a UNESCO Heritage Site since 2000. Baku’s city walls, erected by the Shirvanshah dynasty (Shahs of Shirvan), once contained the whole city until Imperial Tsarist Russia began to construct large neo-classical buildings outside them.

We alight at the double gates in these 12th century walls. As we dally in front of the gates, the guide points out a large platform which is being disassembled after the September Formula 1 race around Baku in the Azerbaijan Grand Prix. By this ancient wall is the narrowest part of the city circuit, just over seven metres wide. A bit tight. The rules, we are told, state that nine metres is the narrowest width allowed but “an exception was made for Baku”. Max Verstappen won this race (2025), incidentally, should you wish to know. The city has a contract to hold the Grand Prix until 2030.

Once inside the gates the fascinating old city is revealed with its mosques, hammams, caravanserai, and opulent residences with wooden balconies on a network of narrow cobbled streets. These narrow streets made it more difficult for the enemy to fight, I gather. And the wooden balconies “were very prized” says our guide “as they showed off your wealth”, i.e. having wood in the desert, a very dry region obviously, was rare. Souvenirs in the form of flying carpets, felt slippers and attractive trinkets grace old walls.

Maiden Tower

The first site of interest is the 12th century cylindrical shaped Maiden Tower, or Qiz Qalasi, constructed from the local limestone. There is some debate as to what the tower was built for. Some believe it was part of the defensive fortifications, others that it was a temple, yet others that it was an observatory. Whatever its purpose, it is now on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. The tower was at one time located on the banks of the Caspian Sea, the world’s largest inland sea/lake. But it has lost water since then, and there is a path with a greenish lawn bedecked with trees on one side, leading two hundred metres down to the Sea, which is currently 29 metres below sea level.

We enter the tower and clamber up stone spiral staircases, worn by countless feet, between floors. Maiden Tower originally had no steps to its first floor, thus preventing the enemy from pursuing the citizens sheltering within, our guide informs us. Said citizens would have been hoiked up by ropes to reach it. I note the massive walls, which are between three and five metres thick as I climb to the top. Exit onto the roof, around which are railings with glass sides, put there to ensure the clarity of the view but to prevent enthusiastic would-be jumpers off from jumping off. Inside the tower is a well, from which those cooped up inside, as many as two hundred, could procure fresh water.

Gasim Bey Caravanserai

From Maiden Tower, we head to the two storey caravanserai built by Shirvanshah I Khalilullah in the 16th century. This is one of dozens of inns, used by merchants trading on the old Silk Road, still standing in Azerbaijan. The Silk Road – or rather a series of roads – ran from China across Central Asia and crossed the Caspian Sea to Azerbaijan and beyond.

This two storey caravanserai belonged to Gasim Bey in the 17th century, according to the info provided. Afterwards his heirs lived in it, since when it has been used variously as a customs house and a museum. It is now under state protection as ‘a monument of national importance’ and hosts a restaurant. The courtyard is surrounded by balconies, from which drape carpets, and rooms for guests are behind. These are arch shaped with colourful carpets on the floors and drapes on the walls. A niche experience it would be to stay here.

Continuing along the old streets we pass a foursome of local men in the shade of a rather lovely house. Two are playing backgammon, a popular game in Baku, we are told, while two look on pensively. An elegant lady alongside flaunts her sheep wool hat. To the right of the backgammon players is a building housing the Baku Caviar Boutique. “Let me tell you, when I was young…”, begins our guide, “I ate a lot of black caviar, because there were many many sturgeon in the Caspian Sea at that time”. He frowns. Now, through overfishing and pollution there are less fish, and caviar has become expensive. The Caspian Sea’s bounty, of which oil is today’s most sought after product, is divided between its surrounding countries (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Russia, Iran and Turkmenistan).

Juma Mosque

Next on the itinerary is the Juma (Friday) Mosque, first built in the 12th century on the site of a Zoroastrian temple, Zoroastrianism being the religion practiced in the region in ancient times. The mosque was rebuilt in 1899 by an oil baron, but the Soviets, in their determination to ban all things religious, used the mosque as a carpet museum. Better than a warehouse I suppose (see Baltic States, Part 2: Latvia). The mosque resumed its proper function upon independence. Anyway, shoes removed, headscarves wrapped round female heads and the group enters. Exquisite decor within, with geometric motifs,

calligraphy, graceful arches and an ornate pale green carpet with sections delineated for each worshipper to kneel upon. Floral carvings decorate the Mihrab (the niche in the wall indicating the direction of Mecca).

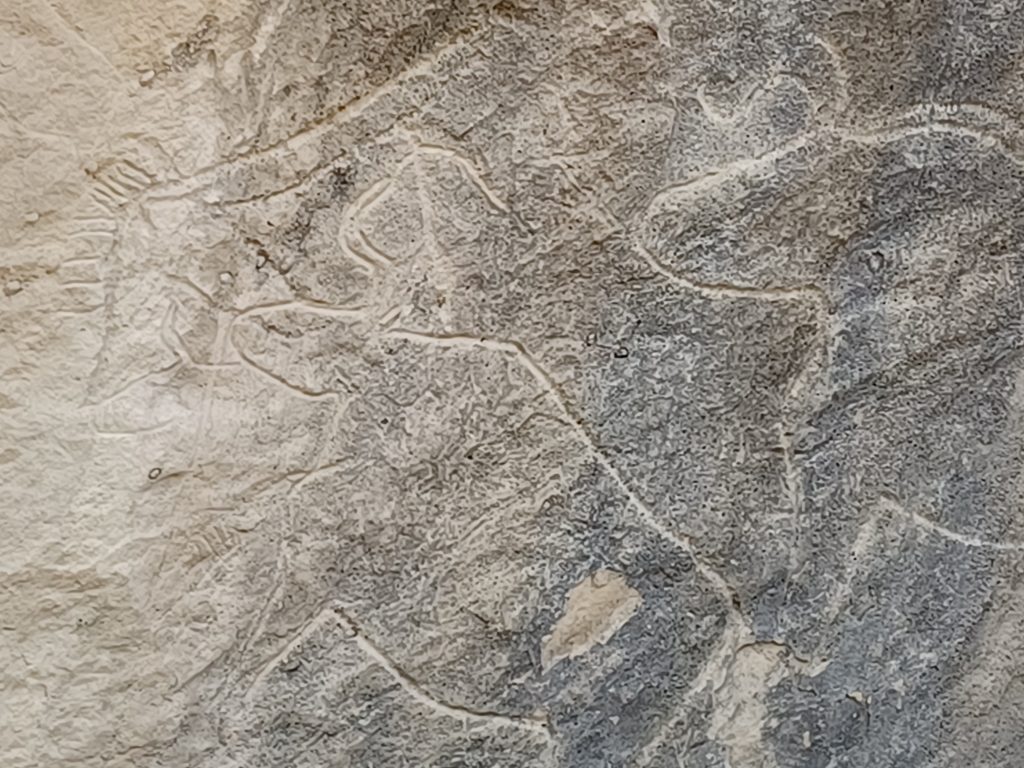

Free time. Rejoice. Off to explore some tempting ruins in Bazar Square next to Maiden Tower. Within the 12th/13th century ruins are stone cloisters with arches and carvings thereon. This was once the main market place for silk road traders as well as a sacred site. 52 ornate tombs were found when the site was excavated in 1964. Placed within is a rock with petroglyphs of animals on it and other carved stone figures and animals. Also near the walls of Maiden Tower are the remains of St Bartholomew’s Church. St Bartholomew, one of Christ’s twelve apostles, having attempted to convert the Zoroastrian fire worshippers, was martyred here in 71 AD. Built in 1892 the church was destroyed by the Soviets in 1936.

Up a side-street I spot a modern rendition of the old Ghir pourers, those who would have waterproofed rooves of buildings back in the day. And I chat and drink tea with the owner of a backstreet café.

The group reassembles and we resume our tour of the old city. Stop briefly to observe the Gasim Bey hammam. 17th century. This is the place to go for your complete body scrub, should you so desire. The men bathe five times per week, the women only twice on Mondays and Fridays. Our guide tells us, somewhat gleefully, that in the old days mothers would go peep inside at the naked ladies with a view to eying up the good ones for their sons. Arranged marriages don’t happen these days, so we are told anyway.

Via one of the old city gates we exit the walls and wander through a park where a pianist is playing the piano – a great tradition in Baku – while parakeets screech in the treetops. Said parakeets arrived at the country’s border without papers, our guide tells us, and were forbidden entry, whereupon their guilty owner opened their cage door and set them free. They seem to like it here.

From the park we admire many buildings including the two towered Azerbaijan Theatre of Opera and Ballet. We view the elaborate glass Isheri Sheher metro station with its flying carpet shaped canopy over the entrance. The metro station inside is, apparently, a work of art. We sidle past a quince tree, a structure with signs of the zodiac round it, and a large bronze bust of a satirical poet, Aliaga Vahid. Then enter the city walls again through the Salyan gate.

The Palace of the Shirvanshahs

Now to the Palace of the Shirvanshahs, which occupies the highest point in the old city and is generally considered the most significant site in Baku. The palace, as with Maiden Tower, is built of the local limestone and consists of several buildings and courtyards.

We are brought up short in the first courtyard we enter by a sombre reminder of wars: scattered bullet holes deep in the walls. Armenians massacred thousands of innocent civilians in Azerbaijan in 1918, including in Baku, our guide informs us.

Hastened through a doorway on the ground floor, we assemble to be regaled on the history of the Shirvanshahs. This dynasty ruled Shirvan, the eastern province of Azerbaijan, from 861 to 1538, their most flourishing period being during the 15th century. The palace here was built in 1411 by the 33rd Shirvanshah, after an earthquake had damaged the previous capital, Shamakhi, situated about eighty miles to the west of Baku. It was completed by his son, Shirvanshah I Khalilullah, he who also built the two storey caravanserai, we saw earlier. The Shirvanshahs fortified Baku, which became an impregnable port on the Caspian Sea. These rulers were wiped out by the Turks in one go, according to our guide, in 1538. Their ancient lands were seized and the Shah’s library and most of their treasures looted.

A large map of Azerbaijan has been placed on the wall here on the ground floor. The shape resembles an eagle, its beak being the Ashberon Peninsula, poking out into the Caspian Sea. Pointing to the map, the guide explains that President Trump has negotiated a peace deal in which the corridor – between the main part of Azerbaijan and a separate part to the south-west, with Armenia in between – will be named after himself: The Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP). Pat on the back for Trump and a step closer to gaining the Nobel Peace Prize no doubt. Both the Armenian PM and the Azerbaijani President endorse his candidacy.

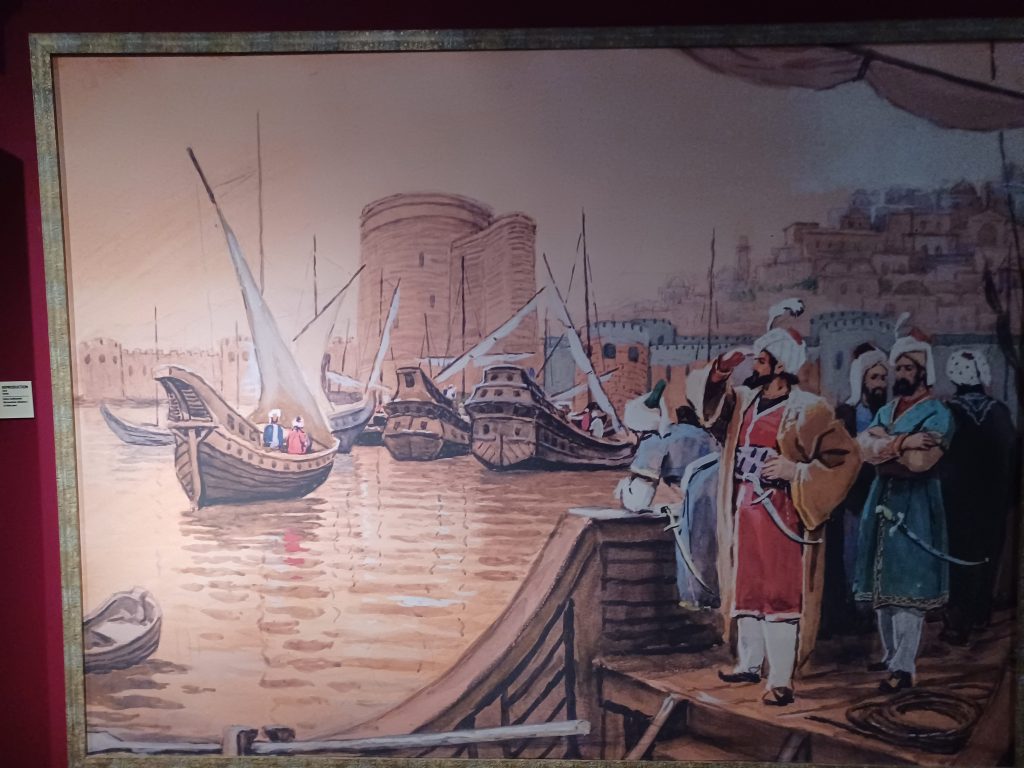

We wander through the Palace rooms. A painting of Maiden Tower with boats alongside it, in the days when the sea flowed round the tower, is displayed in one room. We view the throne room, and another room containing a model of the old city. Thence to the 15th century pavilion, where Shirvanshah I Khalilullah held his court. Splendid building in an octagonal shape with a dome atop.

Educated and enriched, we take our leave of the Old City. And as we are driven back to the hotel we observe the newish Flame Towers which are lit up with 10,000 LED lights dancing round like flames. Dinner tonight is in a restaurant serving some traditional local delicacies: dolma, which is lamb meat wrapped in vine leaves, and plov, a rice dish with lots of fruit and chestnuts and lamb. Lamb has been specified to the chef as the carnivorous fayre of choice due to the fact that several group members cannot eat beef or are allergic to chicken or some such thing. That leaves the vegetarians, who get something special. All suitably catered for, we tuck in to the feast. Thus endeth the first day.

Qobustan Petroglyph Reserve

The ping of the alarm announces it is time to arise. Had been quite unable to slip into silent slumber as the traffic noise was loud and constant even at 04:00. Breakfast is good though: yoghurt with fig jam and fruit, and waffles with honey from the honeycomb. And after breakfast, we board the red coach bound for Qobustan (or Gobustan) Petroglyph Reserve where more than 6,000 petroglyphs await our arrival. Along with hundreds of humans as it turns out.

We drive south west of Baku through arid countryside dotted with oil rigs. “Let me tell you, they pump over 5,000 barrels of oil each, every day”, we are informed. The late President Heydar Aliyev’s portrait appears on posters and placards everywhere. Many places are named after him. Our guide gives us a brief history. He, Heydar Aliyev, became the 3rd most important member of the Soviet Politburo and was head of the Azerbaijani KGB in 1967. In the bad old days after the USSR broke up in 1991 there was civil war in the country as well as war with Armenia over the Nagorno-Karabakh region. Heydar, who had retired to the western part of Azerbaijan – the separate part, possibly soon to be connected by Trump’s TRIPP corridor – was asked to become president, after two other presidents had only lasted a year each. “He did three important things”, our guide emphasises. He stopped the war with Armenia, calmed the civil war and invited investors to invest in the oil industry. He succeeded thus in stabilising the country.

His son, Ilham Aliyev, took over the presidency in 2003 after Heydar’s death and has been running the country ever since. He it was who regained Nagorno Karabakh from the Armenians in 2023. He remains popular and much respected, we are told. Supremely enlightening stuff as we wend our way to the ancient petroglyph reserve.

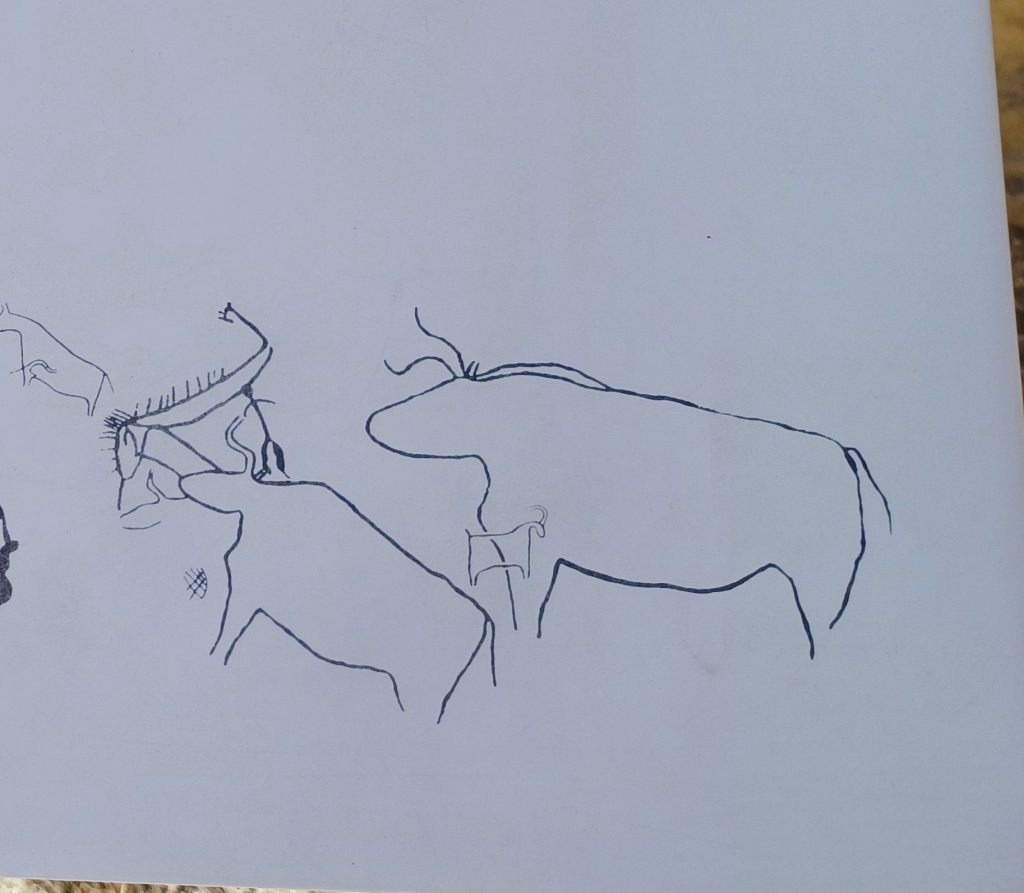

It being Sunday, day trippers are out en masse posing in front of every petroglyph. We visit the museum here first where artists have copied the glyphs so we can better visualise them: drawings of aurochs and boars and wild horses, human figures, foxes, fish, bows and arrows, boats, camels. Emerge from the museum into the midday sun to tackle the ‘excursion route’ round the reserve. Scattered all over the site are rocks which have been split apart and tossed about in all sorts of directions and angles due to earthquakes.

And upon the rock faces, prehistoric peoples depicted scenes from their lives. The climate was a whole lot wetter then than now and the animals they hunted have since disappeared. The petroglyphs depict these animals along with the weapons used to hunt them: spears came first, succeeded by bows and arrows, which allowed the hunters to despatch their prey from further away. We follow man-made paths between rocks with their carvings. Not that easy to discern. Might have been better to view the glyphs with a little shadow, at a later time of day, to enhance the contrasts. Even so, one can make out a camel on one rock, followed by two bulls face to face with a horse, two more bulls and a boat; and a wild boar with what appears to be a lion sneaking up behind it.

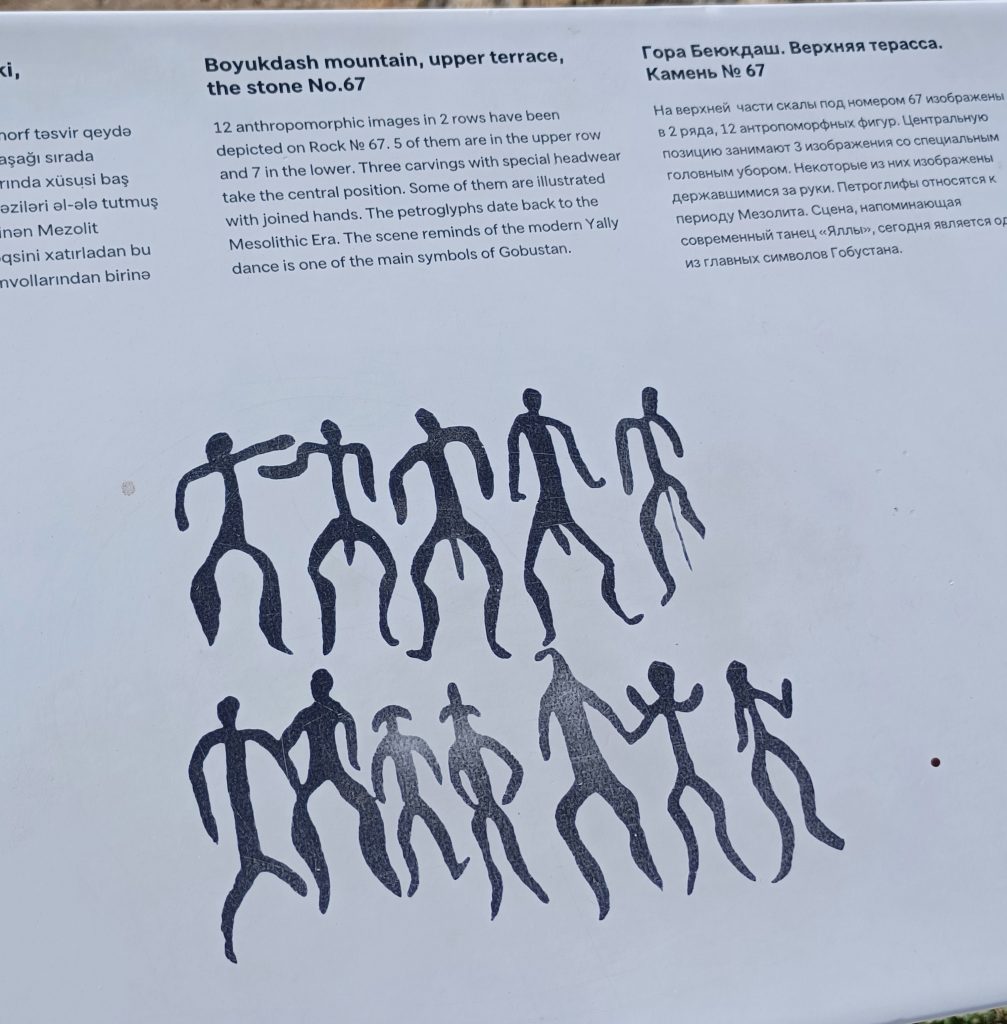

Then, on top of a pinnacle, twelve human beings in two rows. A lower centre threesome seem to be sporting headgear.

The landscape is a bit grey and dusty. The area would have been covered by savannah in the Stone Age, we are informed. The Caspian Sea sits placidly in the distance with a flat dryish floodplain betwixt it and the rocks.

Meander back down the stony pathways dodging human beings. A spear would be handy to part the ways but selfie sticks are the modern weapon of choice. Gain the low ground, and make for our conspicuous coach. We are heading back to town now to visit Baku Boulevard. Our driver passes parked cars within millimetres, I notice. Good luck or judgement, I wonder. No attention is paid to zebra crossings either. Pedestrians are doubtless prudent.

Baku Boulevard

The boulevard is a grand place for a stroll and to enjoy the architectural curiosities along it. We alight from the red coach onto said boulevard to learn that it was built by the oil barons in the early 20th century as a result of Azerbaijan’s oil boom in 1872. This boom came after the end of the Russian empire’s monopoly on oil extraction. “Let me tell you…” begins our guide, “that investors and locals alike became millionaires almost overnight”. “The first to invest”, says he, “were the Nobel brothers from Sweden”. They set up an oil production company in 1879. After which the Rothschilds got in on the act. The grandiose new buildings erected along the boulevard reflected their wealth. Many of the buildings were designed and built by Polish architects, apparently.

Time for a break before our stroll. We hie to the lotus shaped shopping mall and entertainment centre, actually named the Deniz Mall, designed by an English company, Chapman Taylor. Here to take in the view and take photographs from the third floor. A few sea birds are mucking about on some reeds on the Caspian. I watch them through my binoculars for a while before joining the girls in the group (composing of seven solo females, one solo gent and five couples) for refreshments.

Carpet Museum

Afterwards we meet outside the carpet museum. The building is extraordinary, shaped like a rolled carpet. Built in 2014 to showcase Azerbaijan’s unique carpets, part of the country’s national heritage. The carpets were once housed, as said earlier, in the Juma Mosque, thence for a sojourn in the Lenin museum, later renamed the Baku Museum Center, and finally to this purpose built museum, designed by an Austrian architect, Franz Janz. About 6,000 carpets are here displayed, from 17th century to more recent, along with such displays as traditional weaving, ceramics and metal work. But we have no further leisure time to actually enter the museum, somewhat of an oversight on the part of the tour company, I feel.

Two chaps are pruning an olive tree as we wander along the carpet’s front edge. And opposite the carpet is a ‘Little Venice’ with a couple of ‘gondolas’ plying the waterways and Venetian look alike bridges. Apparently an Azerbaijani businessman visited Venice and was so delighted with what he saw that he wanted to bring a bit back to Baku. He did. In 1960, Baku’s Venice was established. Picturesque and tranquil it seems with gardens and trees ornamenting the waterways.

Flame Towers

Ahead of us are the three iconic Flame Towers beckoning over the rooftops. These represent the country’s connection to fire and Azerbaijan’s second oil boom, when BP was invited to develop the oil fields of the Caspian Sea. “Let me tell you” begins our guide, “that Heydar Aliyev signed the contract of the century” when BP came in, as well as other companies, to develop Azerbaijan’s oil industry in the Caspian Sea. That was in 1994. This second oil boom resulted in further beautification of the boulevard and the modern shiny glass buildings echo those of the ‘stan’ countries and Dubai, he says. The resources have also enabled the country to improve its infrastructure and put funds into schools and hospitals etc.

Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre

The red coach sallies forth and picks us all up for a drive along the boulevard. Here we can eye the pre-Khrushchev neo-classical buildings along the road; the blue coloured Hilton Hotel; a government building behind which the Formula 1 race begins and a white monument with 44 columns commemorating the winning of the 2020 Nagorno Karabakh war with Armenia, which lasted 44 days. Further on comes the Ritz Carlton building and then the stunning Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre, designed by the late Iraqi/British architect Zaha Hadid, a female. We alight. No straight lines or corners to this structure. Sinuous lines resembling waves. Not so well known is the fact that many homes lived in by Baku residents were demolished to make way for this building. We don’t enter. I gather that inside is a museum and a room dedicated to the late President Heydar Aliyev. A sign, ‘I love Baku,’ sits at the bottom of the slope.

Thence to pass by the Olympic Games stadium, in which the games were held in 2015. More ultra-modern structures mixed with those of pre-Khruschev Russia line the road as we head eastwards out of the city towards the eagle’s beak.

Leave a Reply