Valentine’s Day. Not exactly a romantic outing planned for today, more of a sad, sombre and thought-provoking one. I am embarking on a tour to Kanchanaburi where the Bridge over the River Kwai is located, along with the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery and the JEATH Museum. This will be followed by a journey along the infamous Death Railway, which was laid from here to Burma between 1942 and 1943.

Thailand was invaded by the Japanese in 1941 during WWII and was forced to surrender to them. The Japanese then established bases in the country, after which it was a relatively simple step for them to invade the British colonies of Burma, Malaya and Singapore. The British surrendered Singapore to the Japanese on 15th February, 1942 (See travelogue: Singapore) after which the Japanese took more than 130,000 Commonwealth prisoners. Many of these were sent to work in Thailand to build the bridge over the River Kwai and the railway line to Burma (now Myanmar). The raison d’être for the railway was to enable a shorter and more secure supply route between Thailand and Burma. The line was to be 250 miles long through the mountains and jungles, along with workcamps for 60,000 POWs and 200,000 forced labourers from the local communities. This line would link to existing railways.

I am picked up at the ungodly hour of 0630 at my hotel. The only reason for booking this particular hotel is because this River Kwai tour uses it as a pick up point. Sensible, I thought, as it saves messing about in the early morning trying to find the meeting place in an unfamiliar city with its atrocious traffic. Good move. There are five of us in the group: four ladies and one man: Dutch, Canadian, Japanese, me and an Australian plus a Thai guide and a driver. Takes a couple of hours with toilet stops through nondescript countryside and the odd Buddha perched on wayside hillocks.

Kanchanaburi War Cemetery

The first stop is the War Cemetery at Kanchanaburi. The War Cemetery is maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, as is the one I visited recently at Kranji in Singapore. It contains the remains of Prisoners of War (POWs) and forced labourers who were involved in building the Death Railway and the Bridge. By the time the line was completed in 1943, over 16,000 POWs had died and half of the local labour force as a result of disease, mistreatment, malnutrition and exhaustion. After 1945 their remains were brought to the War Cemetery, along with some from elsewhere.

I am visiting a day before the 83rd anniversary of the Fall of Singapore. I enter through the three arched stone gateway into the peaceful precincts of the Cemetery. A simple War Memorial of cream stone with a cross and a black sword stands in line with the entrance.

As I walk among the gravestones I realise that there was a large Dutch contingent as well as Commonwealth POWs, who built the bridge over the River Kwai and the railway. In fact more than 1,800 Dutch and 5,000 Commonwealth POWs are buried here. There were also some American POWs involved. Their remains were repatriated, I understand. The long rows of gravestones are all neatly tended with plants between them. Water is being sprayed right now to keep the grass green. I wander between the Dutch graves to take photos for the Dutch lady on the tour, who has mobility issues. I note many British Army Service Corps gravestones, Royal Engineers, and the Gordon Highlanders. Someone has stuck a few little Scots flags into the earth alongside these latter.

JEATH War Museum

From the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery, we are taken to the JEATH War Museum, on the banks of the River Kwai. Established in 1977, the museum is dedicated to the victims of the Kwai Bridge and the Death Railway. JEATH stands for six countries involved: Japan, England, America and Australia, Thailand, and Holland.

The flags flying at the entrance are those of Thailand, Great Britain, Netherlands, USA, Japan and Australia. On the information board to the left of the entrance is a quote which was used by the Japanese commander in the 1957 film: “If you work hard you will be treated well but if you do not work hard you will be punished”.

The museum holds a collection of exhibits associated with the construction of the Death Railway. Interesting and moving they are. They include a replica of a bamboo hut with a palm thatched roof, similar to that which the prisoners would have lived in, and photographs and articles written by former POWs. Apparently the Japanese did not mind photos being taken or records made to start with but later forbade it due to their treatment of the POWs reflecting badly upon themselves. We are led past drawings showing the POWs’ tired and emaciated bodies, implements such as mess tins and spoons, water canteens, Dutch and British helmets, weapons and other items owned by the prisoners.

The information signs tell us that the railway was built in sixteen months before being bombed by the Americans. One of the bombs used to destroy the bridge failed to detonate and is on display in front of the bamboo hut. The 1957 film shows that a British Special Unit blew up the bridge with dynamite. “Wrong!” Moreover, it was filmed in Sri Lanka, not in Thailand.

The 1957 film, according to our guide, was the best of Hollywood fiction but the atrocities carried out by the Japanese, he believes, were downplayed in the film. I had watched it on the flight to Bangkok, so it is still in my mind’s eye. Various forms of torture were performed such as forcing the POWs to drink quantities of water, and attaching them by the arms and leaving them naked outside to be bitten to death by mosquitos.

The guide asks us: “Do you know why they wore no clothes?” Answer: “Because the POWs had previously hidden weapons [beneath their clothing] and if naked except for a sarong, they could not hide any weapon”.

A large board with map shows the location of the POW camps along the route of the railway line.

The Bridge over the River Kwai

From the museum, we clamber off the nearby jetty onto a motor boat in which to approach the bridge by river. Glorious scene. A few oxen are cooling off in the water close by and a large white statue of Buddha, floating restaurants, and Pepsi signs adorn the river.

It is noticeable that the left six sections of the iron bridge consist of low arches but two of the sections on the right are larger. These latter were bought from the Japanese after the war to replace the bombed sections. Ironic to say the least. The Japanese sections are not in keeping with the POW built sections, the original three spans having been replaced with two for some reason. According to our guide, the British Government sold the bridge to the Thais after the war. The money was used as some form of compensation to neighbouring countries for their losses to the Japanese, apparently.

The 332 metre long bridge is supported by concrete pillars with riveted iron sections on top. Not a wooden bridge as portrayed in the film, though there was also a wooden one built first. We finally disembark on a jetty and proceed to walk over this remarkable structure.

To make it easier for the tourist traffic to walk across it, metal boards have been laid over the wooden sleepers and hand rails erected each side. Not too many tourists today. A lady sits begging on the bridge in the shade. I continue to follow the railway line after the bridge comes to an end, eventually coming to a hut cum guard post with a sign on it: ‘River Kwai Bridge’. People pose inside. The line continues. It is still used today but part of it, we are told, has returned to nature, that bit being in the jungle where nobody lives. Thus there is no longer a connection to Burma, which was the original intention.

The guide tells us it was known as the Death Railway because one man died for every sleeper laid. On a sign post are the words: ‘If we count all of dead men combine with all captives, foreign laborers and Thai workers, we would imply that ‘one life of them exchanged to one Railway sleeper’.’

Train ride on Death Railway

Now we are going to the station at Nam Tok, about 50 miles west of Kanchanaburi, and about 177 miles from where the line ended in Burma at Thanbyuzayat. There were 36 POW camps built between the bridge and Thanbyuzayat. While awaiting the train, we are led to a huge cave by the railway line, which was once used as a hospital. Within it sits a golden Buddha. Back to the now exceedingly crowded platform. We wait and watch as the yellow fronted train shunts slowly to a stop.

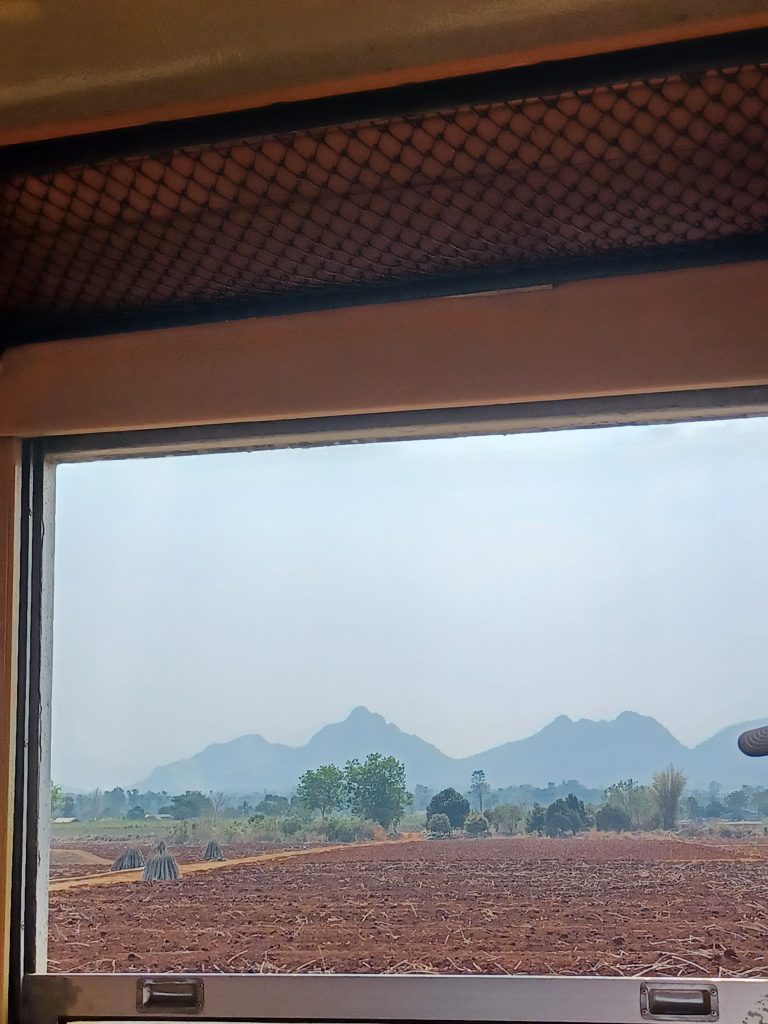

We board the train into our reserved carriage with old wooden seats. Gaze at the countryside through the windows as we chug eastwards. Bucolic scenery: ploughed fields, distant mountains and the peaceful meandering river flit by the window. A cheery trader comes by with some sort of doughnuts and bread for sale.

We ride for over an hour. The train is scheduled to travel as far as Bangkok but we stay on it only as far as the Bridge over the River Kwai. This we slowly cross, peering down from the windows into the depths of the river. Then disembark at the station.

An engrossing day. An idyllic spot. Mood is mixed. The beauty of the present day surroundings is haunted by those events of 80 plus years ago. The Bridge over the River Kwai, along with the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery and JEATH Museum, serve as sober reminders of what happened here.

Leave a Reply