Corinth Canal

We are driving westwards in a minibus from Athens through pale greenish hilly countryside with our main guide for the tour, who gives us the lowdown on interesting landmarks. Every now and then we catch a glimpse of the glittering waters of the Aegean Sea as we approach the famous Corinth Canal. “The canal is four miles long and cuts through a narrow isthmus separating the Peloponnese peninsula from the mainland”, our guide informs us. A canal had been envisaged way back in antiquity, apparently, by the tyrant of Corinth, Periander, in 602 BC, in order to cut 300 miles off the distance between the Ionian and Aegean Seas. But nothing was actually done until 67 AD when the Roman Emperor Nero, he who, in popular myth, fiddled while Rome burned, used slaves to construct a canal. Nero was murdered before it could be completed. The Venetians had a go but didn’t finish it. It was finally built in the 1890s, only about 2,500 years late.

We disembark and walk to the bridge. Below us is a narrow channel of blue water between precipitous walls, three hundred feet down. That must have taken some digging out. One or two trees and bushes have claimed a foothold on the walls and a couple of birds are buzzing about but otherwise all is still. It is quite spectacular. Marvellous it would be to pass through the canal on a boat but it is off season. The only vessels that use the canal these days are small cruisers and tourist boats as it is not wide enough for modern ships – only about 80 feet. Anyway, there are no vessels today.

Mycenae

Having piled back in the bus, I resume my place on the front seat. Funny how people are creatures of habit. I claimed the front seat behind the driver on day one and have sat in it ever since. “We are now going to the great city of Mycenae”, begins our guide. “It is said to be the city of Agamemnon, son of Atreus. In mythology, it was Agamemnon, King of Mycenae, who fought against Troy in the Trojan War,” as was recounted in Homer’s epic poem, the Iliad. Agamemnon commanded the armies from around Greece, known collectively as the Achaeans.

I had learnt something about the Bronze Age and important sites across Europe during university days and Mycenae was the subject of a series of lectures as I recall. “The city was once the seat of a great civilisation and the Mycenaeans ruled over a large area of present day Greece, Crete and west Anatolia,” we are informed. Lasting from about 1600 to 1100 BC, its golden age probably dated between 1350 and 1200 BC with a population thought to be about 30,000. Fire destroyed the citadel in 1100. Isolated on a hilltop with massive ‘Cyclopean’ walls (as the Greeks first thought they had been built by the Cyclops) around the top, the ancient citadel sits surrounded by a grassy area criss-crossed by pathways, cypresses and olive trees, overlooking the plains of Argolis and distant mountains. The site was excavated by the German archaeologist, Heinrich Schliemann, in the 1870s and was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1999. Schliemann wanted to discover whether there was any truth to Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey stories, particularly as to the apparent abundance of gold at Mycenae.

Up the slope we head towards the main gate to the citadel. There is a terrific view from this once strategic position and centre for trade in the Mycenaean world. Near the gate and either side of it are thick walls of cut stones, and atop is a stone lintel with two lionesses facing each other. A symbol of Mycenaean power. The heads are missing. We pass underneath it and enter the citadel. Our guide, with encyclopaedic knowledge, describes the royal graves found within the citadel’s walls.

Accompanying the nineteen skeletons, Schliemann found all sorts of precious grave goods, including about fourteen kilograms of gold, within six shaft graves in Grave Circle A (date: about 1600 BC), immediately to the south of the Lions Gate. There were items of gold jewellery, gold cups and diadems, faience vessels, items of silver and amber, and bronze swords to name a few. The most famous artefact found, however, was the Mask of Agamemnon, a death mask made of gold, placed over the face of one of the male bodies. “He sent a message to the King of Greece: I have gazed upon the face of Agamemnon!” proclaims our guide. Although this is disputed, the death mask still retains his name. Agamemnon was murdered by his wife, Clytemnestra, on his return from Troy.

Inside the walls was also a great palace where those in power ruled in luxury. Spears and a helmet made from a boar’s tusk were found here, among other things. Lesser mortals, like artisans and merchants, lived outside the walls. In fact, our guide tells us, in some of the merchants’ houses here, archaeologists found tablets with the Linear B script on them. This was the first form of the Greek language and written in syllables. None of these artefacts remain to be seen on site, most of them being in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

It requires some imagination to visualise the city in its gleaming glory amongst the ruins but our articulate guide, a mine of information, explains in depth as we trample around the rough pathways.

A couple of us descend a longish way down steep stone steps, sixteen I count, through a corbelled tunnel made of stones towards a secret cistern, an underground spring, on the east side of the site. “This was the main water supply.” We only descend as far as the massive ‘Cyclops’ gate, whence there are another 100 or so steps down. The water was led to the cistern via clay pipes from a spring outside the walls, our guide explains. There are other remains of wells inside the walls too, the water being collected from roof tops during the rainy season.

Down the road, well outside the walls, we venture through a long straight entrance corridor lined with tall stone walls into a huge beehive tomb, called a ‘tholos,’ said to be the tomb of Agamemnon or ‘Treasury of Atreus.’ It is the grandest and most strategically placed tholos on the site. There are eight others. Dating to around 1250 BC, it was built well after the Grave circles within the citadel’s walls. “The façade was once decorated with sculptures”, but no more. “Some of them are in the British Museum”. It appears that Lord Elgin was responsible for the removal of these, as well as the Parthenon artefacts. Hmmm. These included parts of two green marble columns either side of the tomb entrance. The British were not the only ones, though. The Germans also obtained some fragments from the façade, now housed in e.g. the Karlsruhe Museum. Inside the tomb, one can see the brick shaped stones which form the corbelled structure, circular layer upon circular layer with the circles getting smaller as the walls ascend. My fellow group members look miniscule inside.

Epidaurus

Our guide beckons and once more we weave across the wild and rugged hills of the Peloponnese. This region is said to be where Herakles carried out the first six of his twelve labours. These included the slaying of: the lion from Nemea; a snake like sea monster with many heads known as the Lernean Hydra; and the Erymanthean boar, of which the populace were terrified. Not hard to believe. Anyway, Herakles succeeded in carrying out all his labours. Unsurprisingly, he was known as the strongest of the offspring of Zeus ‒ Zeus himself being the chief god in the Greek pantheon. Herakles used a club made out of the wood of the olive tree to assist in his success. There are olive trees all over the Peloponnese, a symbol of power and victory, as well as peace, apparently.

We shortly arrive at the huge theatre at Epidaurus. “The theatre is part of the sanctuary of Asklepios, god of healing”, we are informed “and ceremonial healing practices were carried out here”. The whole complex is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The theatre itself is a wonder to behold and was built in the 4th century BC by the architect, Polykleitos. “It can accommodate 12,000 people, it has perfect proportions and is the best preserved Greek theatre anywhere,” enthuses our guide. The bottom row of seats had back rests. “This is where the nobility sat,” and he points out the remains of one of them. We are propelled up a narrow aisle to the top row of seats to look down upon the circular stage, the hills and trees providing a stunning backdrop. The acoustics are awesome. Our guide poses dramatically, centre stage, while the six of us, the only people in this vast theatre on this sunny February day, harken to his stirring address. The theatre is still used for performances but not, sadly, in Winter.

Nafplio

Nafplio is the next port of call, a delightful port town situated in the Gulf of Argolis. It was the Greek capital for a brief period after Greek independence.

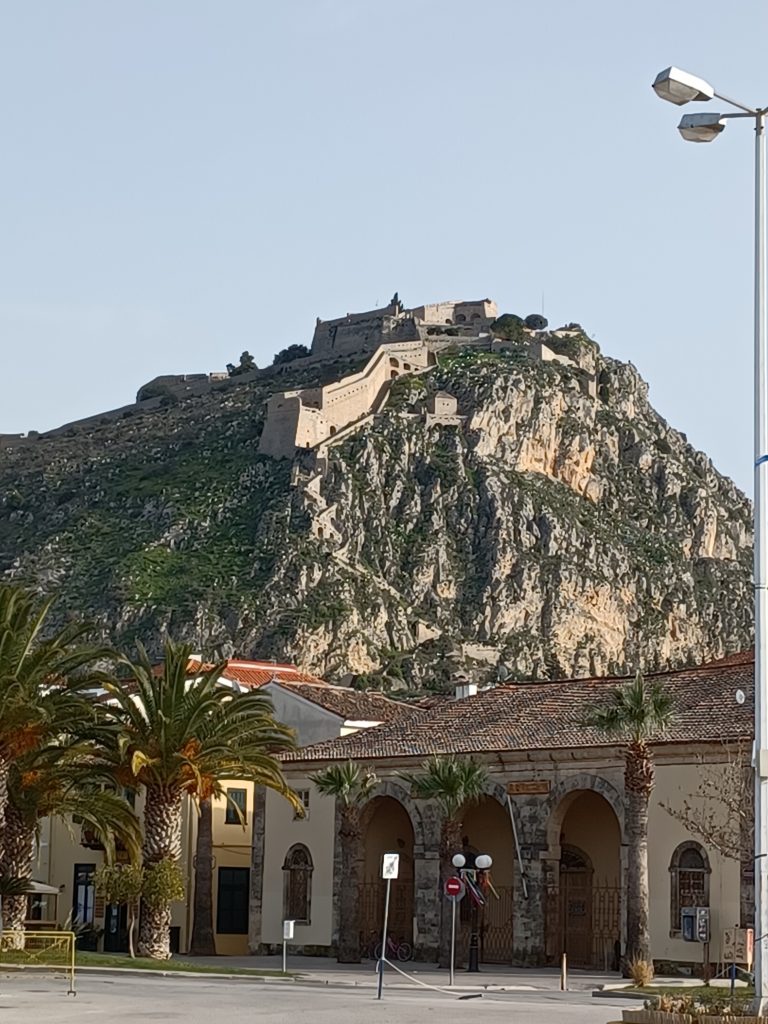

Behind the town rise the impressive ramparts of the Palamidi fortress, to which there is a steep stone stairway with 999 steps right to the top. “You can climb all the way up”. Perhaps not. “The fort was built in three years by the Venetians,” we are told. “Between 1711 and 1714”. There are eight bastions connected to each other. One of these bastions was used as a prison when the Ottomans took over the fortress. The Greeks took it over during their struggle for independence in 1822, while during WWII it was occupied by the Nazis.

The Hotel Grand Bretagne with its pale pink and yellow walls is our haven for the night. The flags of Greece and the European Union fly from a balcony. I deposit my bags and head out for a snack with others in the group. A taverna, lavishly supplied with local foodstuffs, fits the mood. Spinach pie with feta cheese in filo pastry along with a bowl of Greek yoghurt and a jug of the local red goes down well. Supposed to be a starter but quite sufficient. Saunter slowly back to the hotel. Old furnishings and a bathroom with a bath. Soak gloriously in the tub, the perfect antidote to a long day.

I like Nafplio. Palm trees line the promenade overlooking the Venetian Bourtzi Castle on an islet in the harbour with a backdrop of the distant mountains. Atop the castle the Greek flag, with its nine horizontal stripes of blue and white with a white cross in the upper hoist, is flying cheerfully. The cross symbolises Eastern Orthodox Christianity, I gather. White painted rowing boats are bobbing on the water and across the harbour a tall ship lies at anchor.

I stroll round town admiring the old Venetian buildings, one of which, the old arsenal, now houses the Archaeological museum. Other old structures, such as mosques, were built by the Ottomans and have since been converted. Between alleyways I spot the nineteenth century clocktower of Nafplio atop the walls of the lower fort, the old city lying at its feet. I wander through hidden courtyards, pass an orange tree full of oranges, and old tavernas. I continue across the main Syntagma Square with its colourful buildings with shutters and balconies, and cafés. Shame to leave really, I ponder, as we shortly drive out of town up the winding road to the top of the hill whence there is a magnificent view across the bay.

Olympia

Ancient Olympia, dedicated to Zeus, is our destination today. It was during the festival of Zeus that the Olympic games took place, in which the city states of ancient Greece competed. The games were held every four years between about 720 BC and 400 AD. “The winners of the first Olympic games were presented with a crown of olive branches as a symbol of their victory,” we are informed, and “the same happened in the more recent 2004 Olympics at Athens”.

As with the other sites we have visited, hardly any other tourists are at Olympia. Our guide leads the six of us beneath an archway, under which the ancient athletes would have passed, to arrive at the stadion (stadium). The ‘stadion’ was the standard unit of distance ‒ actually named after the running race, the most prestigious event in the games. “The course was 600 Olympic feet long”, we are told. That is 192.27 metres.

We are poised at the starting position, marked by low stone blocks with grooves in. “The grooves were designed for the runners to put their toes in”. “Three, two, one!” and we are off running – well sort of ‒ along the sandy stadium, imagining the spectators sitting either side on the grassy banks cheering us on. Unlike the naked Greek athletes though, we are fully clothed.

There are many ruins here, including the remains of the once towering temple to Zeus, which dominated Olympia. There were twelve metopes on the temple depicting the twelve labours of Herakles. Inside it was once a sculpture of the God by Phidias, he who sculpted the statue of Athena in the Parthenon. Apparently this statue was one of the seven ancient wonders of the world. The only temple dedicated to a human rather than a god, that of Philip of Macedon, is the Philippeion. It has three Ionic columns still standing and once contained statues of family members, including his son Alexander the Great who, according to our guide, completed the building in 336 BC.

We see the temple to Hera, wife of Zeus, in which was found a statue of Hermes with baby Dionysos. A statue of the emperor Hadrian was also found inside the walls here. We view the hippodrome where there were horse and chariot races and, close to the river Kladeos, a swimming pool, serving the athletes. Nice. Our guide endeavours to make sense of the ruins. Once again, it is rather difficult to imagine it all so it is also helpful to see a model of the site in the museum, along with the remains of many statues and artefacts. It is a shame that they are not in situ. The ruins seem rather lifeless without the statuary. Even so, we have had a glimpse of what ancient Olympia once looked like.

Close by, we stop at a touristy place selling Ancient Olympia olive products. The cultivation of the olive tree is the chief agricultural activity in the Peloponnese today. In fact, Greece is the third largest producer in the world of olive oil after Italy and Spain. Most of its oil is also extra virgin, meaning that it has less impurities than mere virgin olive oil, I am told. Anyway, we sample various kinds of olive oil. A plethora of skin products are also on offer. No obligation to buy of course when several merchants are breathing down your neck. I succumb. Some extra virgin olive oil, olive oil soap and olive oil moisturising cream are shoved in my back pack with the binoculars.

Lunchtime. A rather congenial restaurant has been booked for us with white chairs and tables within a long white painted veranda with white roof beams. Outside are pot plants in an old wooden barrow and a little swimming pool. Greek olive oil is served with luscious salads, grilled meat on skewers and pita bread, accompanied by a glass or two of Olympia red wine. Naturally. Stagger back to the bus for the next stage of the tour.

Leave a Reply