Accompanied by my imperturbable driver, I am heading away from the Coromandel Coast now through unremarkable villages and busy roadsides. Hanging on branches of trees on strings are bunches of bananas or coconuts touted by roadside hawkers. An old man sits in front of his tiny hovel, and sleek black goats pick through the rubbish. It must be difficult though, even for goats, to find anything amongst the piles of non-bio-degradable plastic and tin foil. Every now and then, we come across a bit of new road. Slung across newly painted railings are bits of hessian or plastic sacking. Elsewhere, somewhat more delicately draped, is someone’s household washing out to dry. Nishad accelerates to about 100 km/hr for about a kilometre, until the new tarmac runs out, then slams the brakes on as we bump along uneven streets once more. The underside of the car is scraping along the ground as we proceed too fast over another bump. “Sorry,” he says.

There is much poverty here. As we wait in a queue to cross a bridge, an old man approaches my window begging. I am told that there are plenty of organised begging gangs in India. I can’t think this old chap is part of any gang though. He is wearing a dhoti – a piece of cloth fastened at the waist ‒ as most men do round here. Some are full length, others are folded up to the knees. Pale blue and grey check seems to be a favourite pattern. The beggar soon wanders off. Meanwhile the women in their brightly coloured saris have flowers in their well-groomed hair, which is brushed back into pony tails. A considerable contrast to their menfolk.

Gangaikondacholapuram

We soon arrive at an awe-inspiring granite temple in a village with an unpronounceable name. Actually if you split the names into syllables, it becomes easier to work out the pronunciation. Said village is called Gangaikondacholapuram. ‘Puram’ means town in Tamil, while ‘Gangai’ means Ganges, as in the river, and ‘chola’ refers to the Chola empire. Not sure what the ‘konda’ bit stands for. The temple here was built by King Rajendra I in 1035 and the then city was capital of the Chola empire for 250 years. The temple is similar to but smaller than the Brihadishwara temple in Thanjavur that we will be visiting later. It is dedicated to Shiva. I do not venture inside as I am not sure – at this stage ‒ whether I should, not being a Hindu. So I saunter round the grounds and am soon accosted by three skinny young lads. “Grandmother, Grandmother”, they call. We chat awhile and I take their picture.

We continue. After more sections of potholes interspersed with tarmac, I finally arrive exhausted at the air conditioned Laxmi Hotel in Thanjavur to recuperate for a short time before the local guide is scheduled to take me to the Brihadishwara temple, or ‘Big Temple’. This temple is the most famous Chola monument in Tamil Nadu, built by Rajaraja I between 1003 and 1010. The local guide introduces himself as Raj (Ruler). He is highly articulate. He orders me to take a photograph from a distance of the 16 storey high pyramid shaped granite temple, its crown sculpted from a monolith. I do so. “The monolith was put on top via a seven kilometre ramp,” he says.

The site is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is dedicated to Shiva. Having removed my shoes and socks – obligatory on entering sacred places ‒ I am told to take a photo of one of two gopuras (gateways) in the late sunlight. I do so. The gopuras are guarded by a menacing figure each side, and the main uprights, I am told, “were brought from fifty miles away, transported by elephants”. Inside the vast courtyard, there is a massive statue of Nandi, the bull, on a platform under a magnificent painted ceiling supported by four carved pillars. A queue of devotees to see the main temple winds around the courtyard. I do not go inside.

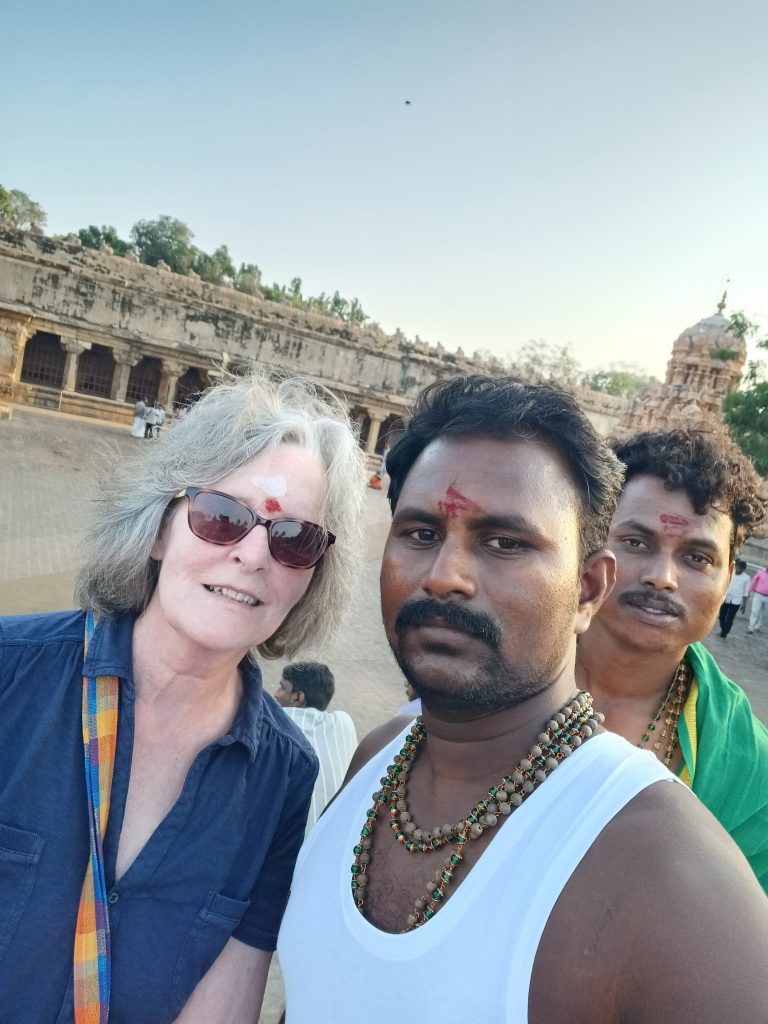

I soon find myself being instructed to enter some of the smaller temples dedicated to various deities. Good job I have some small denomination rupee notes in my pocket as I hand a few of them over to a Brahmin at each shrine, in return for a blessing and a daub of red or white powder on my forehead. The shrines include one dedicated to Parvati, one to Ganesha, and one to Kartikeya, Ganesha’s elder brother, the god of war, whose vehicle is the peacock. I see 27 Shiva lingams in three rows of nine – the number nine, I am told, is significant, but I don’t remember why ‒ and fantastic paintings on the walls of various gods. For example, the goddess Kali (incarnation of Parvati), associated with destruction, is depicted with eight arms and a blue face, and a carving features the man equals woman Shiva/Shakti. Out in the courtyard I am approached for a selfie by two youngish men with moustaches, wearing beads round their necks and red powder on their foreheads. Why they desire a selfie with me in my old shirt and baggy trousers, I cannot understand. I am at my least elegant, especially in comparison with those svelte Indian ladies.

Raj then leads me into a workshop where a tiny man with a black moustache is making bronze figures of the Hindu gods using the lost wax process. I watch the process, knowing I am going to be persuaded to buy a souvenir at the end of it. Gullible visitor number one, that’s me. Figures of Shiva/Shakti and others are held up for inspection but I finally purchase a figure of Ganesha with his pot belly, four arms and elephant face. Not exactly charming looking but there are redeeming features: Ganesha is a welcoming god, the god of new beginnings and is thought to bring good luck. He is widely worshipped in India and most devotees have an image of some sort of him in their homes. I was to see many Ganesha statues in roadside villages and towns throughout Tamil Nadu and beyond.

Delicious vegetarian curry in the hotel restaurant that night. A glass of wine would have been welcome but I have found none at all in India so far. Not part of the culture. However, a rather nice feature of checking into hotels here is that, whilst going through the procedure of handing in one’s passport to be photocopied, writing down details of whence one has come and whither one is heading, one is invariably presented with a glass of fresh fruit juice. This serves to soothe the fevered brow and quell the queasiness. Pineapple today. I wonder vaguely where Nishad will be spending the night. It seems that hotels often provide a room for drivers, or at least a bathroom, but he seems to sleep in the car most nights. Always well turned out though. He and his fellow drivers have a WhatsApp group, by which they find out who is where and when and meet up. Seems like he has a sociable time.

Tiruchirapalli

En route next day to Trichy, or Tiruchirapalli, to give it its full name, there is quite a long stretch of newish smooth highway. A considerable relief. I am met in Trichy by a middle aged well-nourished guide wearing white shirt and trousers, which bear the shiny signs of wear. He talks constantly and, whilst clearly a mine of information ‒ “I been guide 36 year”, there is some difficulty in my understanding him due to his Indian English pronunciation. I gather that he is guiding a group of Koreans with their interpreter this afternoon. I wonder how they will get on using this universal global language with its infinite varieties.

Trichy’s dominant monument is the massive Tiruchirapalli rock fort with a temple to Ganesha on top of it. I tramp barefoot up the 487 (I am told) steps to the top. The first part is in the shade and, although the treads of the steps are high, there are hand rails to assist the weary. The second part is in the open air in the midday sun. Quite a hike in 35 degrees or so. A party of cheery school girls in check uniforms overtakes me. Hmmm. I ponder why on earth I putting myself through this. However, some elderly Indian ladies – much older than I ‒ are also ascending the steps, so I cannot be seen to be doing a humiliating about turn. Mind you, they are on a pilgrimage to worship at the shrine of Ganesha, whereas I am merely ascending for the view. I reach the top via some final steep steps with yellow painted railings. Some pilgrims are resting and picnicking on the rock itself having ducked under said railings.

The modern town spreads below us with trees dotted about. I see a graceful church – dedicated to Our Lady of Lourdes, apparently, with a fine spire. The river Cauvery (also known as Kaveri) runs in the distance. Not much water in it, I notice. The guide refers to the river as the “Southern Ganges,” a sacred river, as many Indians come here to bathe in it and have death ceremonies performed for their lost loved ones alongside it. The Brahmins who perform the rites “make 2000 rupees every time.” “Rich people,” says he, somewhat enviously.

Ranganathaswarmy Temple

The other dominant site in town is the incredible Ranganathaswarmy Temple dedicated to Vishnu. The temple site is huge and has several gopuras, which I observe from inside the complex from atop a roof. One is plain white, signifying purity, while the others are multi coloured and depict all sorts of fantastical figures and animals. In the distance is a golden dome, which “is made of 24 carat gold plate”. There is a long queue leading to the main temple. “Main temple biggest in India”, I am told. It is covered with statues to Vishnu and his various incarnations. I am not allowed in.

Once down from the roof we enter a pillared hall, the pillars of which are carved with mythical beasts, such as rearing horses with cows’ tails, bits of crocodiles, elephants and tigers. They are called ‘Yali’ and each is made from a single monolith.

The guide keeps up a persistent patter. Meanwhile a live elephant is being handled by his mahout in the hall. Not sure why it is padding about this sacred place. But said elephant has a thin red triangle within white vertical surrounds on its forehead, which I understand represents Vishnu. A sacred elephant then. A tourist takes out her phone to take a photo. “Not allowed!” rebukes my guide. Later, I see said elephant outside, being taken to its bunker for the night.

Near the Yali are large carvings of Vishnu’s nine incarnations. Walking along the row, my guide names them all: “First one fish, second one turtle, third one pig, fourth one lion. Next boy, then here angry man, Rama, Krishna, brother Krishna. Krishna most important incarnation”. At the end of the line is what is thought will be the tenth incarnation. “Last one head of horse ‒ apocalypse!” Dramatically said. We exit the hall and he is interrupted by a member of the public asking for information. It is clear he enjoys the attention. “They see me with you, so ask me. I tell them”. Another man approaches him to ask for his services. “I tell him I guide you. Not possible”. However, he needs to answer some urgent ‘phone call so he tells me: “You wait me here. You take photo here. Five minute, I come”.

As we wander around, we observe a gathering of Brahmins all with white vertical stripes on their foreheads. They are chanting a mantra in Sanskrit, I am told. We come to a large building with columns all round. “British have court here. British people govern here. Last one”. Interesting. I follow him around in my untutored bare feet. “This building have many dynasties: Pallava, Pandya, Chola, Nayak, British rule finish all”.

As we head out of the complex, I notice a Westerner queueing to enter the main temple. Said Westerner stands a blonde head and shoulders above the next tallest person. Not inconspicuous. My guide approaches his guide: “Not allowed in”. He returns to me. “I tell guide, he not know”. Further on a man is interviewing a young lady in a pink dress and he informs me: “She giving wrong information. She not from here, she not know.”

The tour over, we reach the car and he hops in the back to be dropped off somewhere in town. He directs Nishad: “left, right, straight.” Eventually, a well-rehearsed: “Madam, this is end of my services”. I tip him generously and he alights. I look at Nishad, he looks at me and we both breathe a sigh of relief.

Chettinadu

Today is a tad more relaxing and different. We are heading toward Chettinadu, the land of the Chettiyars. The highway is smooth. Much rejoicing. The Chettiyars built grandiose mansions out of the money they made from trade during the time of the British Raj. There are over 70 Chettiyar villages in the region but one of the best in terms of architecture is Kanadukathan. I stay in Chettinadu Court, in a bedroom with yellow, white and brown patterned tiles on the floor, rattan ceiling and an old wooden wardrobe. By far the most characterful hotel so far. The low rise red brick building has a thatched roof and a large area of trim grass and bushes in front. An English couple is checking in. I soon find out that they are touring southern India by motorbike with a guide, travelling in the opposite direction to me – i.e. from Kochi to Chennai. Wonder if they realise what they are in for, in view of all the potholes to come as they motor eastwards.

In the village, I stroll about gazing at the mansions. Most of them are now a trifle dilapidated but were once brightly painted with columns and balustrades. One is turquoise and, high up on each side of the façade, are what appear to be soldiers wearing pith helmets and bearing rifles. Top middle is a statue of some Hindu goddess – Lakshmi perhaps. The odd holy cow wanders along the street and birds chirp in the hedgerows.

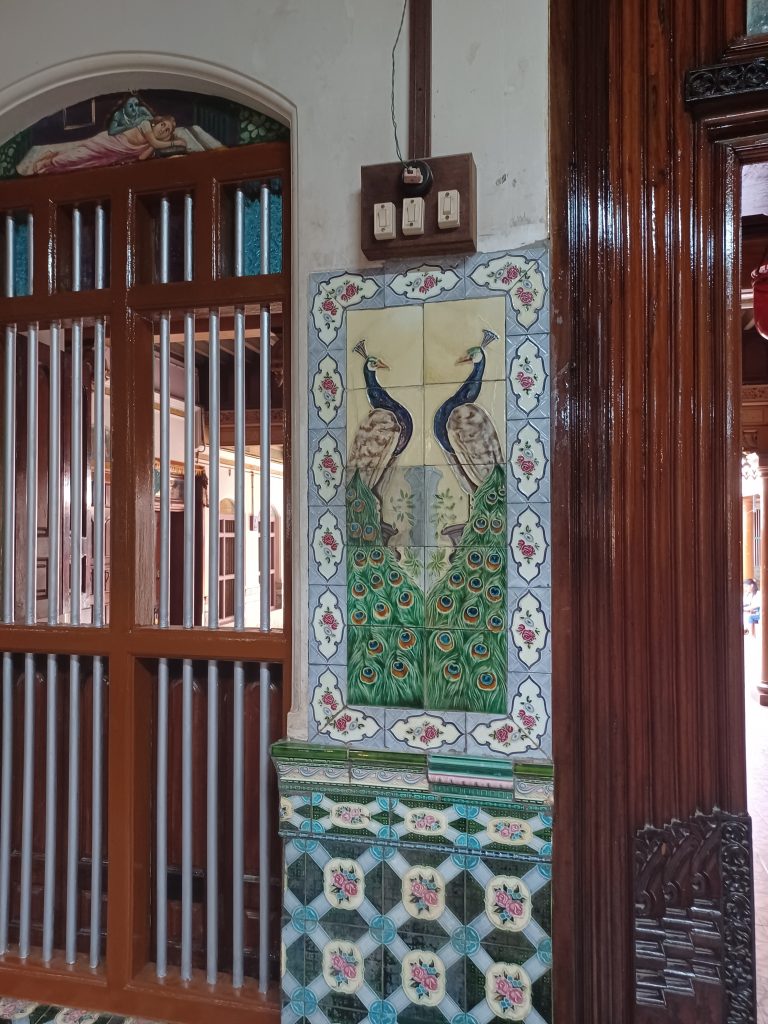

No local guide here. Nishad’s instructions are to take me around to view sites of interest. Thus I am driven to a nearby temple where life-size horses made of mud are lined up on one side of the complex, while a huge statue of a white horse with a green parrot on its head and mythical figures around it, rears in the temple precincts. There are many live green parrots in the trees too. Significant perhaps. We visit one of the tile making cottage industries called ‘Lakshmi Flower Tiles’ where a young man and woman are daubing paint onto large heavy floor tiles. On each tile, they lay a grid and plop the paint into each section to form the pattern. Simple but effective. Close by is Athangudi Palace, one of the stunning Chettiyar palaces with doorways of Burma teak, decorated ceilings, black and white floor tiles, and wide courtyards with columns and arches. One tile wall panel features two peacocks. The whole place is gorgeous.

Meenakshi Sundareswarar Temple, Madurai

The last major temple I am to see in Tamil Nadu is that dedicated to Meenakshi (avatar of Parvati) in the Sri (‘Sri’ means holy) Meenakshi Sundareswarar (avatar of Shiva) temple in Madurai built by the Nayaks in the sixteenth century. It is located on the Vaigai river and the complex is about 14 acres in size. The guide speaks English exceedingly well. Hoorah. And mobile phones and cameras are not allowed in the temple. Even better. This is the only temple which has security at the entrance. But once inside it is agreeable to be able to view it with the respect it deserves without hordes of selfie takers posing all over the place. There are four huge gopuras at each cardinal point and several inner ones, all pyramid shaped with various levels depicting the usual colourful deities, animals and mythical beings from Hindu legends. The most revered temples in the complex are the two golden temples to Meenakshi (this means fish eyes), the principle deity, and Sundareswarar. I am not allowed in them. Devotees come from far and wide, particularly young couples, as the two gods represent fertility. Every evening the Brahmins take their statues to the bedchamber to spend the night together.

Within the complex is a big pond called the Golden Lotus pond or ‘tank’. “People were once allowed to bathe in it, but not now,” I am told. We enter an expansive hall – the hall of one thousand pillars. “Actually there are 994 granite pillars”, says the guide. Also, as in Trichy, there are many ‘yali’, those mythical beasts carved out of stone. In one corner of the hall are some hollow columns, which sound different notes when tapped with one’s knuckles. I tap them of course. The ceiling is highly decorated with lotus flowers. In the past kings and queens would have come here to watch dancers in the evenings, while today families come here and sit and eat or just enjoy themselves.

As we head out of the hall, the Chief Brahmin and two other Brahmins are sitting on a stone step. I am introduced as a lady from England. One of the younger Brahmins asks me eagerly if I am following the cricket. Err no. Nevertheless, he is anxious to inform me that England has just beaten India in the first test match by 28 runs. Good to know, albeit from an unusual source. Clearly he has his mobile phone with him and is able to access the internet in the temple. At the exit to the temple is a large Ganesha statue, in front of which devotees are prostrating themselves on the stone floor.

Leave a Reply