India had not been on my radar particularly. But once rooted in my head, nothing could stop me from planning a trip there. You know how it is sometimes when the name of a country keeps popping up: a friend mentions she had a cracking time there, a documentary about said country appears on the TV, you discover that an acquaintance worked there, and so on. Removing myself from the dreary English Winter – endless rain and cold as is usual in January – and the inevitable anticlimax after the events of the Christmas festive season was high on my priority list. In my view there is no better time to escape.

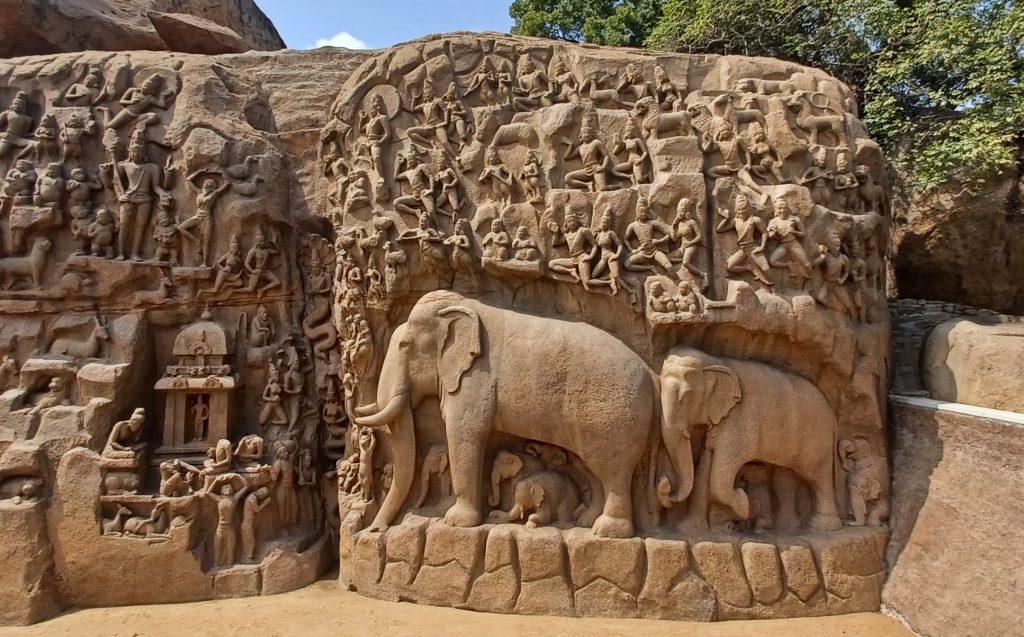

I decided on southern India. Not sure why. Anyhow, the sub-continent is far too big to travel its length and breadth in one go. The plan was to journey from Chennai (onetime Madras) in Tamil Nadu state on India’s south-east coast and end in Kochi (onetime Cochin) in Kerala on India’s south-west coast. The Hindu temples would be the main sites of interest in Tamil Nadu and those in Kerala would be the soothing natural areas of water, woods and tea plantations with their associated wildlife. Seemed a good plan.

Chennai

My first and enduring impressions of Chennai are of pollution and potholes. Thick yellow haze on landing. Atrocious roads all the way to the hotel. The thought of being a passenger on such roads for hundreds of miles in the ensuing days is gruesome to contemplate. And it turns out that I am the only person travelling along with the appointed driver. How did that happen, I wonder. You might think that a tour with a personal chauffeur across southern India is a jolly good deal but it has its drawbacks: paucity of conversation, for example; dining on one’s lonesome, experiences unshared. Advantages, perhaps, may be the possibility to set one’s own timings and, to a small extent, the itinerary.

The hotel is way out of Chennai, situated behind some dusty palm trees and a sandy frontage upon which are lurking several tuk-tuks ‒ auto rickshaws. The bedroom is adequate, I swat a mosquito and collapse for a bit before inquiring at reception how best to discover the highlights of Chennai.

Forty minutes in honking traffic later, courtesy of an Uber taxi, I find myself on the road outside Fort St George, which is surrounded by a twenty foot high wall with indents for ‘Flagship House’ and other buildings of consequence. Fort St George was the first possession of the British in India, founded by the East India Company in Madras in 1639 as a trading post. Tamil Nadu’s Legislative Assembly is the Fort’s most recent resident. Within the complex is a museum which would, no doubt, be interesting to see, containing as it does relics of the British Raj (British rule in India from 1858 until 1947), such as uniforms and weapons, but the driver seems not to understand that I would like to visit, assuming, wrongly, that I must want to visit Marina Beach and heads thither instead.

Marina Beach is long, the second longest urban beach in the world apparently, and is full of people wandering, sitting, picnicking; holy cows ambling about or lolling in the sand; food and drinks stalls, and rubbish. There is only about a metre difference between high and low tide here on the Coromandel Coast. I ponder whether the rubbish higher up the beach gets washed away. Behind the beach are trees of various sorts and behind them rise some old Victorian buildings, which belong to the University of Madras. One of them appears to have a glorious bunch of pith helmets perched on top of it. The other has four splendid domes, arches and columns, built in the Indo-Saracenic style, the style used by British architects in India at the time, which combined Indian elements with British ones. A huge pylon towers over the building.

Chennai is hardly the elegant and graceful city of old. These heritage buildings stand out for their beauty, along with many temples and churches and monuments dotted around the city, which I have no time to see. But most of today’s urban sprawl consists of a dense muddle of modern day structures, telephone wires and traffic. The roads are crammed with 2 wheeled scooters and motor bikes, 3 wheeled tuk-tuks, and 4 wheeled everything else ‒ apart from the holy cows. Cows are sacred in India and allowed to wander at will. I spot one old man pushing a lone push bike amidst the choking traffic. He looks rather bewildered. Meanwhile the driver holds one mobile phone jammed between hand and gear stick and another jammed between hand and wheel, and talks non-stop. He is pulled up by the traffic police and I am left inside the car, engine running, for at least ten minutes. I wonder if he has received a fine, but he doesn’t seem perturbed when he gets back.

We reach San Thome Cathedral (or Saint Thomas Cathedral Basilica), a magnificent white Gothic building glittering in the floodlights as night falls. This church was built by the Portuguese in the early 1500s over what was thought to be the tomb of the apostle St Thomas and rebuilt by the British in 1896. There is a service going on. I wander round the outside admiring the architecture while the driver insists on including me in innumerable selfies. On the way back to the hotel, he exhorts me to speak to his wife and children on one of his phones. I am sure they don’t understand a word.

The drive back is hideous, the taste of pollution on my lips. Takes an hour. Stop start stop start. Eat at the hotel. Soup blows my head off. End of day one. My first taste of India.

Mammallapuram

My guide for the next two weeks is a bit of a gem: Nishad by name, obliging and willing with a good sense of humour. Albeit rather limited in his repertoire. But I understand most of his Indian English and he appears to understand most of my standard British English. It could be tricky otherwise. He drives me southward next day along the flat Coromandel coast road – the name derives from ‘the land of the Cholas’, i.e. the Chola dynasty, who built many of the temples I am to see ‒ on the Bay of Bengal. He drives his white Toyota with consummate skill through an almost continuous urban area of nondescript buildings, swerving around holy cows, road traffic police checkpoints, scooters and potholes. Arrive Mammallapuram and the Mammalla Beach resort too early to check in, but I check out the café, where a sort of striped squirrel is loping around the tables, and order coffee. Splendid location with palm trees along the beach. Not quite such splendid accommodation. Shower never worked.

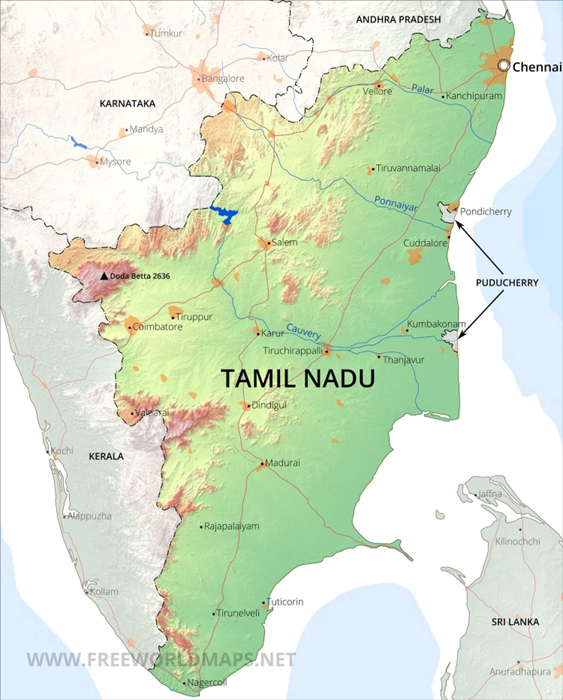

Anyway, the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Mammallapuram is famous for its abundance of stone carved monuments, ancient temples and stone carving workshops. The first ‘object’ that meets my eye though is a natural wonder, the massive granite so-called ‘Krishna’s Butter-ball’, which perches on a slope on a 1.2 metre base, according to the information provided. It appears that it could roll down and crush the multitudes at any moment. A gang of Chinese tourists are goggling at it. One of them, grinning, pretends to support its 250 tonnes weight with his arms.

The local guide then leads me round the site to see the various shrines carved by successive dynasties and dedicated to various Hindu gods. There are three main Hindu gods, I learn: Brahma, the creator, Vishnu, the protector, and Shiva, the destroyer. Here in Tamil Nadu, Shiva and Vishnu are the most important gods and each has a consort – Parvati and Lakshmi respectively. Each deity is associated with a ‘vehicle’ or mount that transports it. Thus, Shiva’s vehicle is the bull, Nandi, Vishnu’s is the eagle, Garuda, Parvati’s is a lion, Lakshmi’s an owl. Devotees worship these vehicles too, as they are regarded as messengers to the gods, as well as their means of transport, and important in their own right.

All the deities have various avatars, in fact Vishnu has nine of them. Add to that, the gods are referred to by different names according to where you are in India or indeed elsewhere. It is all mighty confusing. I suppose that the less informed might, at least, be able to tell which deity is which by dint of the mount. Identification may be further enhanced by counting the numbers of heads and arms and colours or other features in which some are depicted. For example, Vishnu with blue face and four arms, often reclining on a serpent, and Lakshmi sitting on a lotus.

I am led to a cave temple where there are three shrines carved from the rock, dedicated to Brahma, Shiva and Vishnu. Each of the shrines has a pair of gatekeepers either side. They date from the early Pallava dynasty in the late 7th century. Shiva’s has a Shiva lingam in front of it. This is a symbol of the union of man with woman, with a flat feminine part, and an upright masculine ‘lingam’, like a phallic symbol. I was to see Shiva lingams in many temples. Another 7th century temple close by, dedicated to Shiva, has the statue of Ganesha (a son of Shiva and Parvati), inside. Ganesha is depicted as an elephant with four arms. His vehicle is a giant mouse.

Nearby are the ‘Panch Rathas’, five chariot shaped temples sculpted out of single rocks, built by the five Pandava brothers in the 7th century. My guide points out a carving in a niche on the wall of one of them, which is a combined form, half man half woman, which represents Shiva and Shakti (Parvati). “It shows the equality of male and female. The right side represents Shiva, the left Parvati”, I am told. Jolly good.

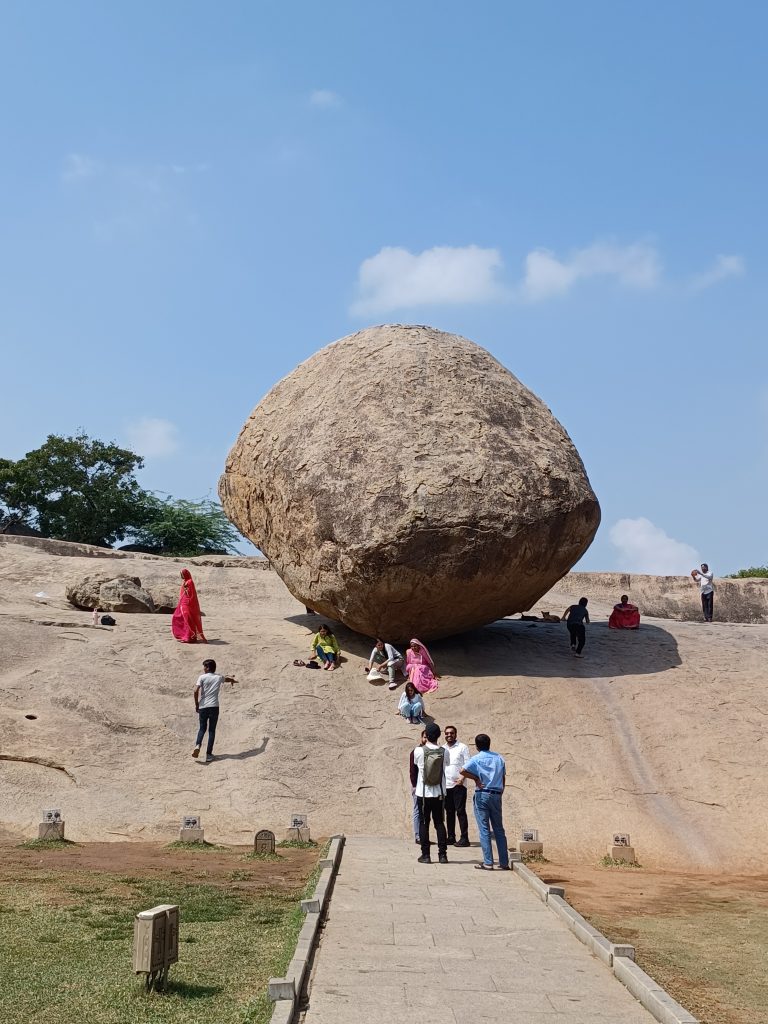

And close by the rathas is a large and famous bas relief carved in the 17th century, ‘Arjuna’s penance’, upon which are huge elephants, along with myriad smaller carvings of deer and other animals and figures. “Indira Gandhi liked the deer carving very much”, I am informed, “so she had them depicted on one of the rupee notes”.

We exit via a narrow road alongside which is a low wall, painted with murals by local artists. “The local men don’t piss against the wall anymore,” whispers my guide, “since these murals appeared”. He then leads me to a studio/shop where students carve figures of the gods and their mounts and sell them to tourists. Hardly a role-model for bargaining, I pay a not insignificant sum for a half man half woman statuette based on the one featured on one of the five chariots. It is carved from marble and rather exquisite. This is the first of many obligatory stops at tourist shops, the next one of which follows swiftly after. Chip chipping sounds greet my ears, as we enter a stone carving workshop and, yes, I purchase a stone carved elephant and a rearing black cobra.

Nearby is the 7th century Shore Temple. Considered of great import, it consists of two pagoda type buildings with two shrines dedicated to Shiva, and one in between dedicated to Vishnu. There is a row of carved bulls in front of the larger Shiva shrine and a Shiva lingam inside it.

There are many carvings of somewhat weathered lions here too, which, I mention to the guide, are similar to those I have seen in China. He replies that “the lions in China were influenced by these lions”. Oh. OK. No doubt the Chinese would say differently. “In December 2004, a tsunami reached the top of the Shore Temple,” says the guide, pointing to bits of the old harbour which ended up in the complex. A wall was built round it subsequently for protection.

Meanwhile on the beach, dozens of Indian ladies in red saris are bathing in the sea to cleanse themselves. They are on a pilgrimage to Kanchipuram, one of India’s holiest cities. I rather wish I was on the beach too, saturated with information as I am. But it is time to head to the hotel and we return to the car, in which Nishad is cheerfully reclining with his bare feet stuck out of the window scanning his phone.

Evening finds me on a beach too. One of those magical evenings, when the full moon is shrouded by the pinkish hue of sunset as the surf lilts up the sand.

Pondicherry

It is a slow three hour drive to Pondicherry next day, due in part to potholes but also to birdwatching. My sainted driver has become aware of this interest of mine and, anxious to please, stops at a number of places by the roadside where birds abound in watery havens in between the urban areas. Some beautiful bee-eaters, drongos, and white throated kingfishers with their long red beaks are perched on telephone wires, whilst egrets, pond herons and storks glide above the waters.

The local guide at Pondicherry is young, slim and earnest. A student of French at the Alliance Francaise, he believes that it is necessary to speak not only English but also French to enhance his guiding skills and job opportunities. His English pronunciation though is barely comprehensible to my ears. I always think Indian English is the most difficult of all English varieties for speakers of standard English to fathom. Anyway, one has to remember, it is doubtless the guide’s third language, so he can be forgiven. English is used in India alongside the official language, Hindi, in government and in higher education, but not necessarily by everyone else. An individual’s mother tongue is generally that of the state in which he or she resides, i.e. Tamil in Tamil Nadu, Malayalam in Kerala. Hindi is the lingua franca between residents of different states, for example between Nishad ‒ from Kerala ‒ and the local guides here in Tamil Nadu. Signposts seem to be in the local language and English though.

Pondicherry is full of gorgeous old French colonial buildings from the time when the town was capital of French India. Some of the street names are still written in French. The town had its own port, lighthouse, customs house, and post office and immigration building. The latter is now a café. Close by the café is a memorial to Mahatma Gandhi, near to which some school children are practicing marching for Republic Day on 26th January. This year is the 75th anniversary. Two men are touching up the Gandhi statue with a bit of paint. Each side of it is a long banner in the orange, white and green stripes of the Indian flag.

I ascend to the roof of the café and look down the long promenade to the old port, which was damaged in the 2004 tsunami and never rebuilt. Marring the scene is the usual debris, which a couple of crows are surveying from the café roof. I observe the old white Hotel de Ville which backs onto the promenade, along with various grand grey coloured buildings which, my guide points out, belong to the Sri Aurobindo Ashram at Auroville a short way out in the countryside. This ashram is open to people of all nationalities and is one of the most important ashrams ‒ and one of the wealthiest ‒ in India, I am told. Anyway, after ridding myself of the guide I explore on my own for a while before heading through a square, in which is a large memorial, surrounded by trees, to those French Indians who lost their lives in WWI.

In the morning of Republic Day I observe a small ceremony in the hotel precincts, after which Nishad, promptly at 0900, emerges from the underground carpark, where he spent the night. As we depart Pondicherry, a man wearing a De Gaulle style red kepi and white uniform is directing traffic. It seems that everyone is going somewhere today: motor bikes by the hundred with ladies in their fine saris and golden sandals riding side saddle behind their husbands; tuk-tuks painted yellow darting in and out everywhere and small pick-ups loaded with anything from bags of cement to stacks of sticks. The words ‘Sound Horns’ are painted onto the back of them in large letters, it being customary for overtaking vehicles to hoot before so doing. Two patriotic holy cows are ambling along the central carriageway with their horns painted in orange, white and green colours. Further along one such cow is rummaging around on a roadside verge with its backside stuck out into the traffic; stray dogs cross the road as and when the fancy takes them.

We leave the Coromandel coast road now and head inland.

Leave a Reply