Exploring ancient ruins is one of my favourite pastimes. There was a time when I used to take part in archaeological digs and enthuse over an emerging prehistoric wall or a shard of pottery from eons ago ‒ rich rewards for hundreds of hours of scraping in the dirt with a trowel. The fascination with things old has never quite left me. Thus, extraordinary though it is, I have waited until retirement to see the major archaeological sites of ancient Egypt. Egypt, with its four thousand or more years old temples and tombs along the Nile, provides open air museums like no other. The hundreds of huge columns smothered with paintings and carvings, and the colossal statues still in situ are awe inspiring to behold. Even an averagely interested traveller cannot fail to be impressed.

I decided to take a tour ‒ a tour full of variety including a few nights on a Nile River cruiser and a hot air balloon flight. Visits were to include tombs, pyramids, mosques, museums, churches, bazaars and a Red Sea resort. Something of everything. First of all though, I spent a couple of days in Cairo visiting an old friend. This served to get my bearings, and to do one or two things not specified on the tour, e.g. sail the Nile at sunset on one of those traditional feluccas.

Unsurpassably sublime. A sneak peek was also had of the gates and mosques of the old city and of quite a few mummified pharaohs, who had recently taken up residence in the National Museum of Civilisation.

Giza

The tour group meets at the Oasis Hotel in the Giza area for a pep talk by the organisers and we are introduced to our guide, an affable looking chap with a bald head and dazzling white teeth in a broad smile. He turns out to be the personification of good nature and fun, yet also erudite and informative. Quite the best sort of tour guide. He advises us to purchase an Egyptian sim card, which I do not do and subsequently regret, and one by one we choose any optional excursions that we would like to participate in. There are 31 of us in the assembled group.

The pyramids at Giza are first on the agenda. I had visited Giza once before, in my youth. It was a quick trip west from Suez and I rode a camel in front of the three pyramids. Back then one could just turn up and walk around the dusty plateau with no hindrance to enjoyment apart from the baksheesh brigade. The persistent pestering for baksheesh (tips) might mar your total enjoyment of Egypt. But that is how it is. Part of the culture. Egyptians tip Egyptians and it is expected of us visitors to tip for every assorted service, be that the pointing out of a special painting in a tomb, or the offering of spurious information and directions. One has to get into the spirit of doling out baksheesh, keep a stash of low value currency in one’s pockets, and enjoy the interaction.

In contrast to decades ago, today there is a high level of security at the Giza site and we are obliged to put our bags and backpacks through the X-ray machine before entering. My backpack does not pass inspection and the guards remove my binoculars from within. It seems likely that they will be confiscated. I would be miffed to lose them. They are a good German make. But our leader distributes baksheesh to the necessary recipients and my binoculars are returned, with the strict instruction that I do not use them. “Forbidden to use them. OK?” OK. There are evidently some military or security personnel I might spy on. We have a security man with us anyway. Such a presence is considered necessary in the light of the terrorist attacks at Luxor some years ago now, but still in people’s memories. That and the ravages of Covid-19 have diminished the numbers visiting the country considerably, and thus, the Egyptians do all they can to protect tourists. Said security man had been occupying the front seat of the bus, back pocket bulging with some lethal weapon. He keeps a close eye on me now – for a few seconds – but clearly does not perceive me to be a security risk and buzzes off elsewhere.

The three pyramids

We stand in a sharpish cool wind, listening to lyrical descriptions of the ancient Egyptians and their burial practices. There are well over a hundred pyramids in Egypt, built to bury dead pharaohs and to ease their journeys into the afterlife, we learn. The largest and oldest Great Pyramid is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still in existence and was built for the fourth dynasty Pharaoh Khufu in the mid-third millennium BC. The second largest is seemingly the tallest as it is situated on slightly higher ground. This was for Khefre, son of Khufu. Khefre is the Pharaoh who is thought by some to have built the great Sphinx and whose pyramid is aligned with it. The third and smallest was for the Pharaoh Menkaure, son of Khefre. All three used to be encased with a smooth limestone facing, which would have blazed white across the Nile, flowing in front of them at that time before later changing its course. The three pyramids still stand out conspicuously on the horizon and can be seen from Cairo, albeit through an oft-polluted haze.

We are now given an hour or so to wander round at leisure. I stand up close to the Great Pyramid. Each massive stone block reaches the average adult’s shoulders.

Some visitors are filing antlike towards an entrance in its north face. I saunter round the pyramid’s massive circumference, while some of the group opt to ride camels instead, bedecked with colourful rugs and tassels. A couple of them are having some kind of altercation about something (the camels I mean). Lot of bellowing and grunting.

The Great Sphinx

The group meets up again and is conducted towards The Great Sphinx, at which we all gaze somewhat transfixed. The mighty sculpture measures 240 feet long by 62 feet wide by 66 feet high at its maximum. Carved directly from the limestone bedrock, the sphinx has a lion’s body and man’s head, and was thought until recently to resemble the pharaoh Khefre, although new evidence points to its being Khufu’s likeness.

One can still make out the red and yellow colours of the headdress. The nose is missing, as is the sacred cobra which would have risen from the forehead, and the beard. There are various theories for the absence of these usual fittings to pharaohs’ heads, too lengthy to relate here, and anyway my ageing brain only takes in a modicum of information before zoning out.

Dahshur

It would not have been possible to construct the great pyramid without the previous experiments conducted by Khufu’s father, Pharaoh Sneferu, the founding pharaoh of the fourth dynasty. He had tried his hand at building several smooth-sided pyramids. One of these, built in Dahshur not far from Giza, is known as the ‘Bent Pyramid’ because the builders began to construct it at too steep an angle at first, so it was unstable. The angle was made shallower, causing a bend inwards halfway up. The Bent Pyramid still retains its smooth polished limestone casing, lacking on the three pyramids at Giza, apart from a remnant perched atop Khefre’s pyramid. The second pyramid in Dahshur, close by – and also built for Sneferu, is the first true smooth-sided one and is known as the ‘Red Pyramid’ on account of its reddish hue. I go inside both of them.

Very few tourists venture here compared to the Giza site. I chose to come here on one of the optional excursions. No security guards, merely one or two Bedouin sit at the entrances expecting baksheesh for stamping our tickets. They greet us cheerfully and offer to look after our bags. Good idea as there is little room in the tunnels for such appendages. I enter the Bent Pyramid, bent double, and descend a steepish rock hewn passage, in which a sort of wooden ramp and handrails have been constructed, for what seems a very long way (73 metres).

Someone, going up and out, tells me as I am halfway down that it is better to descend backwards. It is. Appreciate the advice. At the bottom there are steps to go up and down again and passages to a chamber, where there might once have been a sarcophagus. I meet a large group of Chinese tourists sliding down a narrow passage and wait a longish while for them to pass before crawling up said passage to another chamber. It is jolly hot and stuffy and exhausting. Not conducive for nurturing arthritic knees either. There is nothing to see except the large limestone slabs of the walls and the several chambers, in one of which I pose for a photo.

Emerging, sweating after the climb back up, into the fresh air, we are informed by our guide, who had declined to accompany us on our little foray, that it is less arduous to clamber inside the Red Pyramid and thus he has left it until last.

There is nothing to see inside the Red Pyramid either, but a sizeable dose of curiosity mixed with masochism has compelled me to fold myself in half again and pop into it. Sneferu’s sarcophagus with his remains have never been found, although one assumes it was placed inside. The construction itself is awesome and I ponder how it could possibly have been built over four and a half thousand years ago. It has three chambers with corbel-vaulted ceilings inside. It is the third largest pyramid in Egypt after Khufu’s and Khefre’s.

The Dahshur area as viewed from the Red Pyramid consists of a bare sandy plain, with a few trees in the middle distance and mud brick buildings. Close by is what was once the ancient Egyptian capital of Memphis, where little remains except for a colossal recumbent statue of Ramesses the Great, a sphinx made of alabaster, and a few columns and carvings on stone.

Most of the extensive ruins, pillaged over the centuries in order to be incorporated into other buildings, are contained within the present village, popping up in gardens between the walls of houses and betwixt the date palms.

Saqqara

The smooth-sided pyramids themselves were preceded by the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, close to Dahshur, which was built for the third dynasty pharaoh, Djoser. The Step Pyramid, we are reliably informed, is the first stone building in the world of such monumental size, dating from the 27th century BC. It looks like its name i.e. with steps or ‘mastabas’ on top of each other. The pyramid is part of a large burial complex or necropolis, which includes other mastabas and a cemetery of the sacred ‘Apis’ bulls. The Apis bull, it seems, was a symbol of fertility and rebirth. The Egyptians embalmed and mummified all sorts of sacred animals, such as falcons and baboons, which are also buried here. In fact, many of their gods and goddesses are represented by animals, such as the cat goddess, Bastet.

The local Bedouin, with or without camels, take advantage of the many tourists milling about to sell their souvenirs. One, with a beaming smile and constant patter, follows me about with his wares so I eventually succumb. I barter for a couple of papyrus bookmarks and a couple of rulers with cut-outs of the hieroglyphic alphabet in them. Undoubtedly useful for interpreting the writing in the many tombs we are later to see.

Aswan

Next is a part of the tour to which I have been looking forward with happy anticipation. The sleeper train from Cairo brings us to Aswan in the late morning. It is about three hours late. “Egyptian trains” shrugs our guide. One never knows exactly when they will depart or arrive. But I spend some enjoyable hours on board looking at life beside the Nile and its irrigation channels. There are many cattle egrets along the water’s edge, their bright white plumage and long yellow beaks very visible on the green strip of cultivated fields along the river. On arrival we embark on the ‘Nile Jewel’, our river cruiser and home for the next few nights. Luggage dumped, we disembark immediately to head out on the afternoon excursion.

Philae Temple

The bus takes us to the embarkation point for dozens of small boats taking tourists out to the Greek temple of Philae. Souvenirs for sale line the jetty: bright turquoise pyramids, alabaster jars, beads, bags and crafts of all colourful kinds. “Yallah, yallah! cries our guide.” Let’s go! We embark. After the dusty plains of Giza and Dahshur, it is refreshing to be on the water in the clear air. The boats are painted in reds and whites with open sides and flat roofs. Car tyres, used as fenders, hang around the topsides. I notice that the Egyptian flag, a red, white and black tricolour with the eagle of Saladin in the middle, is flying off the stern on some boats, from the bow on others. Some boats seem to be flying the flags of their occupants’ countries of residence and one is even flying the EU flag. Odd.

As we motor towards the island we see the first Aswan dam (the Aswan Low Dam), built between 1899 and 1902, in the distance. “This was built to control the flooding of the Nile”, we are told. “Built by the British,” he says, looking at me. I am the only Brit on the tour. Philae temple was partially flooded due to this dam, and tourists would visit the ruins by rowboat. Thus, before the later Aswan High Dam was completed in 1970, UNESCO decided to dismantle the temple and move the whole complex to Agilika island, a very small island close by. Many other monuments in southern Egypt and Sudan, including Abu Simbel temple, were also moved piece by piece at that time and relocated. The consequences of the dam construction resulted in the vast Lake Nasser swallowing up many others, along with many Nubian villages.

Philae temple looks stunning from the water, with large rocky outcrops to the right and palm trees in front. The sun shines off the mellow yellowish stones of the temple. The rocks are coloured black below the high-water mark and we note the old pilings marking the place where the temple once stood.

The main temple was begun by the Ptolomy II in about 280 BC, to honour the Egyptian goddess of fertility, Isis. This goddess was married to her brother Osiris and produced a son, Horus, who is represented as a falcon on some carvings. Isis, shown as having two horns with the sun disc between them on top of her head, was one of the most significant goddesses in the religion of ancient Egypt. Even after Egypt was conquered by Alexander the Great in 332 BC, she continued to be worshipped by the Greeks. After the Greeks, the Romans took over Egypt and continued to worship Isis, as they did in Pompeii, Italy, for example, where there is also a temple dedicated to her.

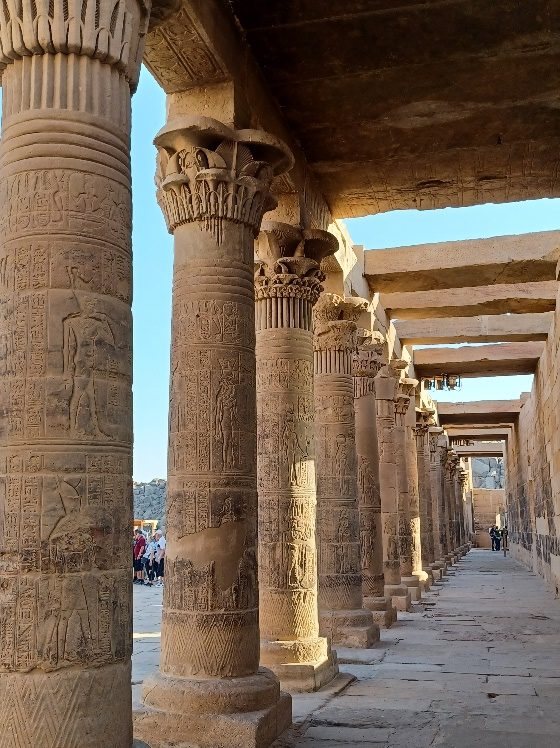

Entrance to the temple is via a massive gateway, called a ‘pylon’, into the forecourt. There are columns either side of the forecourt with a variety of capitals each carved with different floral patterns. Passing through another pylon, we enter into what is called a hypostyle hall, crammed full of columns and walls with carvings all over them of hieroglyphs and figures, such as Isis with her baby son, Horus, on her lap.

Also in the temple are early Coptic Christian crosses, which have been etched on top of some carvings. Christianity arrived in Egypt in the fourth century AD and the religion was accepted by the Egyptians, who, unlike the Romans, did not persecute Christians. However, we are told that pilgrims to the temple continued to worship Isis long after Christianity arrived.

Also to be found on one of the walls is an inscription made by Napoleon’s troops who invaded Egypt in 1798. It was Napoleon’s archaeologists, whom he brought with him on his campaign, who found the Rosetta Stone, at Rosetta near Alexandria. The Rosetta Stone has inscriptions on it in three languages, one of which is Ancient Greek, the second demotic and the third hieroglyphic. The Frenchman, Champollion, had studied Coptic (the basis of which was demotic – effectively the ancient Egyptian script, I understand), as well as Greek. It was this knowledge that helped him, in the early 19th century, to decipher the hieroglyphs (helped by the previous work of others, I have to say, mainly the Englishman, Thomas Young). The Rosetta Stone is now in the British Museum, the British having defeated the French in Egypt in 1801 and acquired the stone.

Fascinating it all is, but there is little time to appreciate it. Our leader waves his hand, the signal to follow him back to the boat, although we just have time to see another temple, the kiosk of Trajan. Trajan was the Roman Emperor in the period 98-117 AD and this building with its fourteen columns was once the entrance to Philae temple from the Nile, we are told. We exit via a different route and thence onto our Nile cruiser for the night.

Moored along a long, paved quayside with several other ships, is the ‘Nile Jewel,’ one of many built exactly the same, each with a large central main entrance so that when they all raft up together, the passengers can exit directly across several ships through the several entrances/exits. They are not particularly pretty, and though advertised as 5-star, they leave a lot to be desired. My cabin is in the stern, close to the engine, sometimes noisy and fumy. But the cabin fittings and fixtures are fine and the food prodigious. When I get back I find that the cabin boy has hung a towel folded in the shape of a monkey inside the door. Very ingenious. I suspect baksheesh is in order.

It is time for the evening meal. Tables are set out for each tour group and staff hover about to take drinks orders. All drinks have to be paid for although the food is included in the price. There is a lot of it. I have never seen so many people eat so much food piled on plates as on this cruise. People of all shapes and sizes crowd round the counters and stack their plates high: all kinds of meats are topped with all kinds of vegetables and separate dishes for salads similarly brim over. How they shovel through it all I know not. I am unaccustomed to stuffing myself to such an extent but make a brave endeavour. And then, looking at the dozen delectable desserts on offer, what can one do but try them all. I am more reticent than some and pluck three or four of the dainty morsels. Nothing for it thereafter but to repose in the lounge in a soft chair with a night cap before retiring.

An optional excursion the next morning is to arise at 0230 and motor across 180 miles of the desert to the southernmost tip of ancient Egypt to visit the temple of Abu Simbel, view it at sunrise with hundreds of others and dash back again another 180 miles before lunch. I decline. I am the only one of the 31 so to do. The problem with such tours as these is that the organisers pack in the sightseeing highlights somewhat tightly. I wanted to take a boat around Aswan, visit some islands, do a bit of birdwatching and get up late. So I did. The great temple devoted to Ramesses the Great would have to wait for another time.

Kitchener Island and a Nubian village

Aswan is warm, January warmth, just right. Warmth that is absorbed into the old stones and warms the bones of those who sit upon them, warmth that welcomes the traveller from colder climes, that heals the shrivelled being, and reawakens the desire to live. Not for nothing were those with poor health in olden days sent off to warm parts of the British Empire to get well, Cecil Rhodes for example, who was sent to South Africa. Well-heeled visitors to Aswan, with or without health issues, were, and are, accommodated in the Old Cataract Hotel, built in the colonial era by Thomas Cook, he of travel agent fame. Winston Churchill stayed here, Agatha Christie sojourned here, and parts of her famous book ‘Death on the Nile’ were set here. Also Princess Diana and Margaret Thatcher, to name a few.

I motor past this imperious hotel with its pink granite façade looking grandly down upon the rocks and pools of the Nile. With me in the boat is a different guide who had agreed to accompany me to explore the area. Feluccas, the traditional wooden sailing boats with one very large triangular sail, sail lazily between the small islands; cormorants and egrets are everywhere, and several pied kingfishers, which are easy to spot. Unlike our resident kingfisher in the UK, which darts off in a blue streak the moment you approach it, the pied kingfisher obligingly sits still as I pass. I expected to see an Egyptian goose but didn’t.

We approach Kitchener Island. Lord Kitchener also came to Aswan on his way to campaigns in the Sudan. The Government was so grateful to him for his service that he was given this island in the river, still referred to as Kitchener Island (it also has an Egyptian name), where he stayed and on which he planted all sorts of trees and shrubs – some from other parts of the empire. They flourished well. The island is now a botanical garden, and is owned by the Egyptian Government. It is not on the general tourist itinerary but I am keen to visit. My boat moors at the bottom of some wide steps with just a few touristy items scattered for sale around about. It is quiet, shady and peaceful. I am a bit late for the birds but, nevertheless, this beats belting back and forth across the southern desert. I amble around Kitchener island for some while before relaxing with a soothing cuppa beneath the trees.

The boat with my guide, lighted cigarette in mouth and constantly scrolling through messages on his mobile phone, approaches a Nubian village. From the river, the dome shaped roofs and brightly coloured walls of blue or yellow stand out against the brown sandy hill rising steeply behind them.

The skipper of the boat, competing with several others to-ing and fro-ing, finds a place to tie up at the bottom of some steep green-painted steps. We wander up and along a sandy path to a bright blue Nubian house. As we sip mint tea inside said house my guide explains that, after the Aswan High Dam was built, Lake Nasser flooded many Nubian villages. A consequence of this is that these people have been scattered far and wide and are gradually losing their language and culture. “Got it?”, he asks after a lengthy monologue, i.e. did I understand what he was saying. “Yes, thanks.” “Any questions?” “No thanks.” It is good to have a guide all to myself. He can be quite informative.

There are a couple of baby crocodiles in a pit in the middle of the large central room. I am not quite sure why they are there except perhaps for tourists to gawk at. Another consequence, of course, of the building of the dam, is that crocodiles no longer lurk down-river of it. One of the gods in the ancient Egyptians’ pantheon was the crocodile god, Sobek, who was seen to be powerful. Carvings of Sobek appear in many of the temples and tombs. My guide lights another cigarette, gets into conversation with the owner of the house and sends me off to explore the village.

A large cloth-covered table of bowls piled with spices is sitting in front of one house. The spices look like miniature pyramids of blue, yellow, white and purple.

Five camels sit nonchalantly on the sand in front of the bright blue house with bright white roof. Above them are tatty telephone wires and a few yards away squats a blue car. Below, the water is glassy calm. The rocks opposite, and which are dotted all over the area, are granite.

There are many granite quarries in Aswan. The granite was used in the time of the pharaohs for huge building blocks and to make obelisks, which were then shipped down the Nile to Thebes (now Luxor) and other sites along the river, where temples were built for the pharaohs. There is an ‘unfinished obelisk’ lying in a granite quarry at Aswan, which would have been the largest obelisk ever carved for a pharaoh. This one was to be for the female pharaoh, Hatshepsut, but the granite split in the process of cutting it out. It is now left for tourists to scramble over.

There is no time for further exploration of Aswan as the majority of the party will be returning shortly from Abu Simbel, expecting lunch, after which the ‘Nile Jewel’ will be casting off to head down-river towards Kom Ombo temple at nightfall. In our small craft, we motor back past Elephantine Island, full of the ruins of ancient Abu and cult centre for the ram headed god, Khnum; we observe the Aga Khan Mausoleum high up on the hill; and we pass several of the other river cruisers rafted up before finally arriving at our mooring.

I thank the skipper of the vessel, hand over the compulsory baksheesh and disembark. On arrival, I see that the cabin boy has folded another monkey shape out of the towel in my cabin, which is suspended from the ceiling. I try to get Wi-Fi. There is none.

Leave a Reply